Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains an important cause of new HIV infections worldwide, especially in low and middle-resource limited countries. Safety data from studies involving pregnant women and prenatal antiretroviral (ARV) exposure are still needed once these studies are often small and with a limited duration to assess adverse drug reactions (ADR). The aim of this study was to estimate the incidence of ADR related to the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in pregnant women in two referral centers in Rio de Janeiro State. A prospective study was carried out from February 2005 to May 2006. Women were classified according to their ART status during pregnancy diagnosis: ARV-experienced (ARTexp) or ARV-naïve (ARTn). Two hundred fourteen HIV-infected pregnant women were included: 36 ARTexp and 178 ARTn. ARTexp women have not experienced ADR. Among ARTn, 20.2% presented ADR. Incidence rate of ADR was 70.8 per 1000 person-months and the most common ADRs observed were: gastrointestinal (belly or abdominal cramps, diarrhea, nausea and vomit) in 16.3%, cutaneous (pruritus and rash) in 6.2%, anemia (2.2%) and hepatitis (1.7%). The frequency of obstetrical complications, pre-term delivery, low birth weight and birth abnormalities was low in this population. ADRs ranged from mild to moderate intensity, none of them being potentially fatal. Only in a few cases it was necessary to discontinue ART. In conclusion, the high effectiveness of ARV for HIV prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) overcomes the risk of ADR.

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains an important cause of new HIV infections worldwide. In 2011, the global impact of HIV on children was enormous, with an estimated 330,000 children becoming infected in low and middle-income countries, mostly through MTCT during pregnancy, labor and delivery or by breastfeeding.1 Great scientific successes have been achieved over the past decade in HIV prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) with the development of effective antiretroviral (ARV) interventions during pregnancy, labor/delivery, and neonatal prophylaxis, as well as with elective cesarean delivery and avoidance of breast feeding.2–4 Antiretroviral prophylaxis prevents HIV acquisition for as many as 409,000 children in low- and middle-income countries.1 Nowadays, PMTCT of HIV programs are implemented in many countries across the world, making in utero ARV exposure and its potential consequences a global issue. Despite the clear success of PMTCT programs and the fact that the vast majority of infants born to HIV-infected mothers can be protected from acquisition of infection, safety data from studies involving pregnant women and prenatal ARV exposure are still needed once human perinatal ARV studies are often small and of short duration to assess adverse drug reactions (ADR).

The aim of this study is to describe the incidence of ADRs related to the use of ARV in pregnant women in two referral centers for PMTCT care and research in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis prospective study was conducted at Hospital Federal dos Servidores do Estado (HFSE) and Hospital Geral de Nova Iguaçu (HGNI), both located at Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil from February 2005 to May 2006. This study was approved by the IPEC-FIOCRUZ institutional review board. Participant eligibility criteria were: (1) pregnant women older than 18 years; (2) gestacional age between 14 and 30 weeks; (3) HIV diagnosis confirmed by serology or HIV RNA viral load; (4) use of at least one dose of any ARV during pregnancy; (5) having had at least one medical appointment after the pregnancy diagnosis.

Women were classified according to antiretroviral therapy (ART) status at pregnancy diagnosis: ARV experienced (ARTexp) or ARV-naïve (ARTn); these two groups were analyzed separately. Women were followed up from pregnancy diagnosis until delivery.

Data were collected by two trained health professionals (one physician and one pharmacist) on the study procedures and definitions. The medical records of all patients included in the study were reviewed in a weekly basis until the end of the follow-up period, in order to update clinical information, focusing on ADR. Standardized forms to collect demographic, clinical, ART and ADR data were designed and piloted before study initiation.

Study definitionsDemographic and clinical characteristics at baseline included: age (years), race (white or non-white), number of previous pregnancies (0, 1–2, ≥3), number of living children (0, 1–2, ≥3), HIV exposure category (sexual, injecting drug use, or unknown), previous AIDS-defining illness, time until HIV diagnosis (months), nadir CD4+ lymphocyte T-cells< or ≥200cels/μL, baseline CD4+ lymphocyte T-cell, highest and lowest CD4+ lymphocyte T-cells during pregnancy, baseline HIV RNA viral load (copies/mL), HIV RNA viral load>1000copies/mL during pregnancy, gestational age at study entry, route of delivery (vaginal route or cesarean section), pregnancy outcome (term birth, preterm birth and abortion), ART use during pregnancy (weeks), ARV modification (at least one ARV of the regimen modified) and type of ART: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), protease inhibitors (PI), NNRTI+PI, or nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) only.

ADR related to ARVs were classified according to information collected from the medical charts, and were grouped as follows: gastrointestinal (GI) (diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, belly cramps), cutaneous (exanthema, pruritus), hematologic (anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia), hepatic, and constitutional symptoms (asthenia).

The most frequent ADR related to ARVs (gastrintestinal, cutaneous, hematologic and hepatic) were graded according to the DAIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Pediatric Adverse Events5 on intensity (mild, moderate and severe). Causality between ADR and ARV was assessed according to6 and defined as definitely, probably and possibly ARV-related. Other caractheristics related to the ADR were also assessed: serious (yes or not), outcome (resolved or ongoing), type of ART (NNRTI and PI), time to ADR onset (weeks), and ADR duration (weeks).

Statistical analysisIncidence rate and confidence interval for each ADR was estimated by Poisson model and reported it as the number of occurrences per 1000 person-months. The statistical software R, version 2.14.1 (www.r-project.org) was used for all statistical analyses.

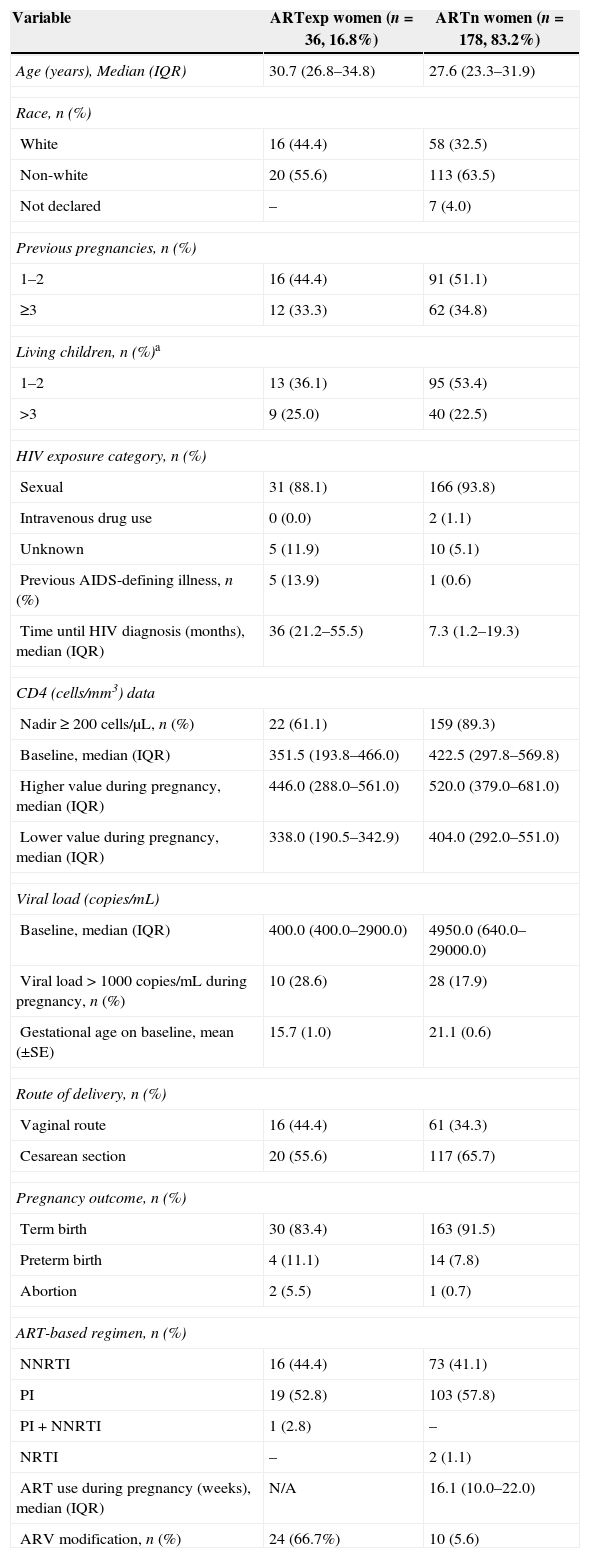

ResultsA total of 214 HIV-infected pregnant women were included in this study; at the time of pregnancy diagnosis 36 were ART-experienced (ARTexp) and 178 ARV-naïve (ARTn). Demographic, clinical and ART characteristics for both groups are presented in Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and ART characteristics for 214 pregnant women included in this study from HGNI and HFSE, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

| Variable | ARTexp women (n=36, 16.8%) | ARTn women (n=178, 83.2%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Median (IQR) | 30.7 (26.8–34.8) | 27.6 (23.3–31.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 16 (44.4) | 58 (32.5) |

| Non-white | 20 (55.6) | 113 (63.5) |

| Not declared | – | 7 (4.0) |

| Previous pregnancies, n (%) | ||

| 1–2 | 16 (44.4) | 91 (51.1) |

| ≥3 | 12 (33.3) | 62 (34.8) |

| Living children, n (%)a | ||

| 1–2 | 13 (36.1) | 95 (53.4) |

| >3 | 9 (25.0) | 40 (22.5) |

| HIV exposure category, n (%) | ||

| Sexual | 31 (88.1) | 166 (93.8) |

| Intravenous drug use | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 5 (11.9) | 10 (5.1) |

| Previous AIDS-defining illness, n (%) | 5 (13.9) | 1 (0.6) |

| Time until HIV diagnosis (months), median (IQR) | 36 (21.2–55.5) | 7.3 (1.2–19.3) |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) data | ||

| Nadir≥200 cells/μL, n (%) | 22 (61.1) | 159 (89.3) |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | 351.5 (193.8–466.0) | 422.5 (297.8–569.8) |

| Higher value during pregnancy, median (IQR) | 446.0 (288.0–561.0) | 520.0 (379.0–681.0) |

| Lower value during pregnancy, median (IQR) | 338.0 (190.5–342.9) | 404.0 (292.0–551.0) |

| Viral load (copies/mL) | ||

| Baseline, median (IQR) | 400.0 (400.0–2900.0) | 4950.0 (640.0–29000.0) |

| Viral load>1000copies/mL during pregnancy, n (%) | 10 (28.6) | 28 (17.9) |

| Gestational age on baseline, mean (±SE) | 15.7 (1.0) | 21.1 (0.6) |

| Route of delivery, n (%) | ||

| Vaginal route | 16 (44.4) | 61 (34.3) |

| Cesarean section | 20 (55.6) | 117 (65.7) |

| Pregnancy outcome, n (%) | ||

| Term birth | 30 (83.4) | 163 (91.5) |

| Preterm birth | 4 (11.1) | 14 (7.8) |

| Abortion | 2 (5.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| ART-based regimen, n (%) | ||

| NNRTI | 16 (44.4) | 73 (41.1) |

| PI | 19 (52.8) | 103 (57.8) |

| PI+NNRTI | 1 (2.8) | – |

| NRTI | – | 2 (1.1) |

| ART use during pregnancy (weeks), median (IQR) | N/A | 16.1 (10.0–22.0) |

| ARV modification, n (%) | 24 (66.7%) | 10 (5.6) |

aExcluding current pregnancy; IQR=interquartile range; SE=standard error.

For the ARTexp group, median time from ART initiation until labor was 23.7 months (IQR6.4–66.4).

Eighteen women (50%) were using an Efavirenz (EFV) based regimen when they became pregnant and have been switched to the following ARVs in order to avoid teratogenic effects: lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) in three cases, nevirapine (NVP) in eleven cases, and nelfinavir (NFV) in four cases. Mean gestational age at the time of EFV discontinuation was 16 weeks (SE+0.8). No obstetric complications during labor were observed and no infants were born with low birth weight or had congenital malformations diagnosed. EFV use was significantly associated with neither abortion nor premature birth (p=0.825).

After the EFV switch, 16 women were using an NNRTI-based regimen, all of them were receiving Nevirapine (NVP); 19 women were using a PI-based regimen, nine with LPV/r, eight with NFV, and one with saquinavir plus ritonavir (SQV/r); one woman was taking an NNRTI+PI containing regimen (LPV/r+NVP). Mean time of exposure to the new ART after EFV switch was 29.8 weeks (SE+1.2).

Six women modified at least one ARV during gestation due to virological failure, three were in use of NVP (switched to NFV) and three were taking NFV (switched to LPV/r). Mean time of exposure to the new ART after virological failure was 4.2 weeks (SE+0.4).

Ten adverse medical events not related to ART were observed: hypertension (4), hepatitis C (HCV) co-infection (1), syphilis (1), ischemic heart disease (1), genital warts (1), pyelonephritis (1), and seizure in a patient with previous epilepsy diagnosis (1). Twenty-six women (77.8%) had no complication whatsover during prenatal period.

Overall, only one obstetric complication was verified, a fetal distress caused by preeclampsia. Only one child had low birth weight (2420g).

Six undesirable pregnancy outcomes occured: two induced miscarriage and four premature births. All pregnant women who gave birth prematurely had a nadir CD4+ T lymphocyte>200cells/μL, two were on NVP and two on PIs. The rate of preterm birth was not different in pregnant women on PI or on NNRTI (p=1.00). Mean baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count was 563cells/μL (IQR 377.25–749.75) and 291.5cells/mm3 (IQR 188.5–291.5) in women who had premature birth and in those who gave birth at term, respectively.

No ADR during pregnancy were observed for all 36 women.

ARV-naïve women at pregnancy diagnosis (ARTn)A total of 178 ARTn patients were included in this study. NVP was prescribed to all 73 patients (41.0%) who were started on NNRTI-based regimen. For PI-based regimens, 93, eight, and two pregnant women received NFV, LPV/r, and atazanavir (ATV), respectively. Two patients received NRTI-only based regimen, one received zidovudine (ZDV) monotherapy and one received a combination of ZDV, lamivudine (3TC) and abacavir (ABC). Eleven women (6.2%) modified at least one ARV during pregnancy, and all modifications were toxicity-driven.

Twenty adverse events (AE) not related to ART occurred among 10 women: hypertension (3), genital herpes (3), syphilis (3), oral candidiasis (2), upper respiratory tract infection (1), conjunctivitis (1), gestational diabetes diagnosed before ART initiation (1), facial cellulitis (1), herpes zoster (1), pyelonephritis (1), sinusitis (1), bacterial vaginosis (1) and scabies (1). Six women (3.4%) had obstetric complications during pregnancy and labor: ruptured membranes (3), perinatal asphyxia and uterine atony leading to hysterectomy (1), failure to progress in labor (1) and placental abruption (1). Only one child was born with low birth weight (2120g). A hundred sixty-two women (91.0%) had no complications during prenatal period.

No statistically significant difference in the rate of preterm delivery in pregnant women according to ART-based regimen was observed. No difference was found in preterm delivery according to the ART regimen received.

Two children (1.1%) were born with congenital malformations diagnosed at birth, both with hemangioma, one on the face and one on chest, and these were not attributed to the ARV exposure.

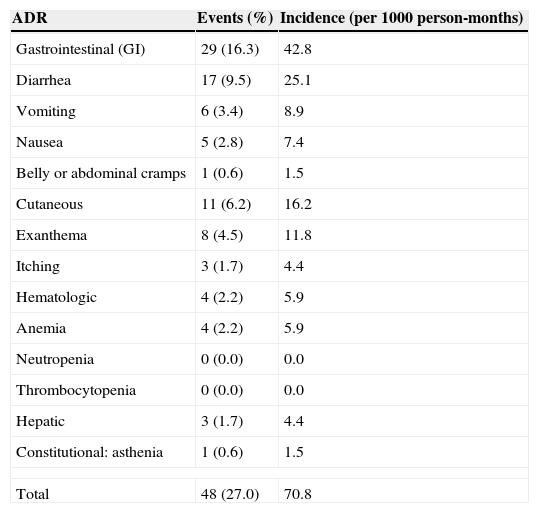

ADR incidence on ARTnAmong those women who developed ADR, mean ART exposure was 16.3 weeks. The frequency and incidence of ADR among the 178 pregnant women enrolled as ARV-naïve are depicted in Table 2. Thirty-six (20.2%) women developed 48 events classified as ADR. Overall ADR frequency was 27% (48/178) and overall ADR incidence was 70.8 episodes per 1000 person-months. Twenty-six, eight and two women experienced one, two or three ADR, respectively. No potential fatal ADR was reported.

Frequency and incidence rate of ADR in 178 ARTn women from HGI and HFSE, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

| ADR | Events (%) | Incidence (per 1000 person-months) |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal (GI) | 29 (16.3) | 42.8 |

| Diarrhea | 17 (9.5) | 25.1 |

| Vomiting | 6 (3.4) | 8.9 |

| Nausea | 5 (2.8) | 7.4 |

| Belly or abdominal cramps | 1 (0.6) | 1.5 |

| Cutaneous | 11 (6.2) | 16.2 |

| Exanthema | 8 (4.5) | 11.8 |

| Itching | 3 (1.7) | 4.4 |

| Hematologic | 4 (2.2) | 5.9 |

| Anemia | 4 (2.2) | 5.9 |

| Neutropenia | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| Hepatic | 3 (1.7) | 4.4 |

| Constitutional: asthenia | 1 (0.6) | 1.5 |

| Total | 48 (27.0) | 70.8 |

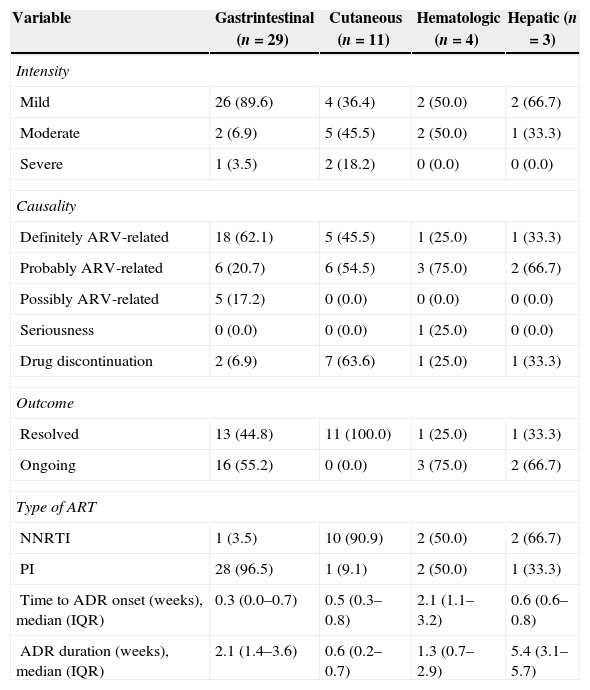

ADR intensity, relationship to ARV, evolution, duration and outcome on women enrolled as ARV-naïve are shown in Table 3.

ADR, intensity, causality with ARV, evolution, duration and outcome in 178 ARTn women from HGNI and HFSE, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

| Variable | Gastrintestinal (n=29) | Cutaneous (n=11) | Hematologic (n=4) | Hepatic (n=3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | ||||

| Mild | 26 (89.6) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (66.7) |

| Moderate | 2 (6.9) | 5 (45.5) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Severe | 1 (3.5) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Causality | ||||

| Definitely ARV-related | 18 (62.1) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Probably ARV-related | 6 (20.7) | 6 (54.5) | 3 (75.0) | 2 (66.7) |

| Possibly ARV-related | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Seriousness | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Drug discontinuation | 2 (6.9) | 7 (63.6) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Outcome | ||||

| Resolved | 13 (44.8) | 11 (100.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Ongoing | 16 (55.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 2 (66.7) |

| Type of ART | ||||

| NNRTI | 1 (3.5) | 10 (90.9) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (66.7) |

| PI | 28 (96.5) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Time to ADR onset (weeks), median (IQR) | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 2.1 (1.1–3.2) | 0.6 (0.6–0.8) |

| ADR duration (weeks), median (IQR) | 2.1 (1.4–3.6) | 0.6 (0.2–0.7) | 1.3 (0.7–2.9) | 5.4 (3.1–5.7) |

IQR=interquartile range.

Eleven women (6.2%) permanently discontinued at least one ARV due to the following ADR: moderate anemia related to ZDV (1); diarrhea related to NFV (one moderate and one severe); moderate hepatitis (1) and rash (7) related to NVP. ZDV was replaced by stavudine (d4T), NFV by NVP and vice versa. Among women starting ART with NVP, 9.6% (7/73) had to permanently discontinue it.

GI events were the most frequent ADR observed and most of them were observed one week after ART initiation. Twenty-four women developed 29 GI ADR episodes (16.3%), including diarrhea (9.5%), vomiting (3.4%), nausea (2.8%) and belly or abdominal cramps (0.6%), with an overall incidence of 42.8 episodes per 1000 person-months. These women were more frequently having a comorbidity during pregnancy (p=0.034), used PI-based regimen (p=0.016), and were in a more advanced gestational age at prenatal care initiation (p=0.014). Mild GI ADR was observed in 89.6% and one woman had a serious ADR. Almost half of these events (44%) were resolved without interrupting ART and in most cases they persisted until labor. Almost all GI ADR (96.5%) occurred in women using a PI-based regimen and only two women had to discontinue their ARV regimen. All episodes of diarrhea were related to NFV (18.3%).

Cutaneous ADR occurred in 6.2% women, including pruritus (3; 1.7%) and exanthema (8; 4.5%), representing an incidence of 16.2 episodes per 1000 person-months. There were three cases of mild pruritus, which were resolved without ART discontinuation. These women were using ATV (1) and NVP (2) in combination with ZDV/3TC. Most cases of rash ranged from moderate to severe (87.5%), but none of them were classified as serious. The only case of mild intensity was resolved without ART discontinuation. All cases of rash occurred in pregnant women using a NVP-based regimen, with an overall frequency of 10.9%. Cases of rash were identified earlier than a week after ART initiation and rapidly improved after NVP discontinuation.

Anemia occurred in four women (2.2%), representing an incidence of 5.9 episodes per 1000 person months. No other hematological ADR (neutropenia or thrombocytopenia) occurred in our study population. All women who had anemia were using ZDV/3TC, two of them in combination with NVP, one with LPV/r, and one with NFV. Anemia occurred for a mean time of 2.3 weeks and it was diagnosed at a mean time of 2.2 weeks after ART initiation. Almost all episodes of anemia were mild to moderate. One case which required hospitalization and blood transfusion was classified as serious, being resolved after ZDV discontinuation in all cases. Anemia persisted until delivery and only one woman had ART interrupted.

Three women (1.7%) had hepatitis, representing an incidence of 4.4 episodes per 1000 person-months. Hepatitis occurred 0.7 weeks after ART initiation and lasted for 4.1 weeks. All cases were mild or moderate and none of them evolved to a severe outcome. Two women were using an NVP-based regimen (overall frequency 2.7%) and one in a NFV-based regimen, both combined with ZDC/3TC. NVP was permanently discontinued in one woman. The other two cases of hepatitis were mild and persisted until delivery.

One case (0.6%) of asthenia was observed in a woman in use of ZDV+3TC+NFV, representing an incidence of 1.5 episode per 1000 person-months. This event started one week after ARV onset and persisted until delivery.

DiscussionOur study provides important information on ARV safety profile during pregnancy from two referral centers for PMCTC in a middle income country where MCTC is still common. The frequency of ADR related to ARVs in HIV-infected pregnant women varies from 5% to 78%, depending on the geographic region, social status, degree of immunodeficiency and length of exposure to ART. Moreover, a favorable outcome is usually observed, with no ARV interruption and without significant or permanent damage to pregnant women and their offspring, which is consistent to our findings.7–10

None of the ARTexp women developed ARV related ADR. These women were receiving ART for over three years. According to the literature, the majority of clinically significant ADR is observed in the first months of ART.11–13 ARTexp women who changed any ARV during the study (EFV switch or virological failure) received a new ARV from the same class (NNRTI or PI), which may have reduced the possibility of ADR related to class switch, such as hypersensitivity reactions and GI intolerance.

In our study, discontinuation of NVP due to ADR was more frequently observed than in a recently published meta-analysis including 20 studies and 3582 pregnant women.14 This could be attributed to high mean baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte cell count observed in our study sample, which is associated to an increased risk of adverse events.14,15 In a Canadian study, continuous NVP use in pregnancy resulted in a relatively higher rate of toxicity when compared to women not receiving NVP, and all cases occurred in women exposed to NVP for the first time during pregnancy.16 This could explain the lack of toxicity in ARTexp women in our study.

The frequency of liver toxicity among pregnant women starting a NVP-based regimen (2.7%) was similar to the lowest rates reported in literature.14,17,18 The average CD4+ T lymphocyte count in our cohort was 457.7cells/μL and CD4+ T lymphocyte counts above 250cells/μL is considered a risk factor for hepatotoxicity.15 This may also explain the above mentioned higher frequency of discontinuation of NVP due to ADR.14 The frequency of hepatitis among women using NFV (1%) was similar to that observed in controlled clinical trials in adults using this ARV (2%).19,20

All ARTexp women were using ZDV for more than three years before pregnancy, and anemia occurs more frequently in the first 12 weeks of ZDV use.21–23 Among ARTn women, anemia related to ZDV was observed in 2.2%, which was lower than that reported in the literature for HIV-infected adults24 and comparable to rates reported among pregnant women.9,25,26 Previous studies with pregnant women showed that anemia is generally mild to moderate, rarely leading to ARV discontinuation or interfering significantly in the health of the pregnant women, which is consistent with our findings.9

The frequency of GI ADR observed is consistent with the literature reports as abdominal or belly cramps, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting are well-known side-effects of PIs. Previous clinical trials with HIV-infected adults on NFV have shown diarrhea in 20% of the patients and nausea and vomiting in 7%. Time between ART initiation and the onset of these side-effects is generally less than one week, with events ranging from mild to moderate in most cases, persisting for long periods in almost half of the individuals.19,20,27

The observed frequency and clinical course of rashes episodes were similar to those reported in clinical trials and observational studies including HIV-infected adults,28,29 and, more specifically, to studies of HIV-pregnant women on NVP.14,15,18,30

No teratogenic effect was observed in any of the 17 infants exposed to EFV during the first trimester of pregnancy, which is compatible to previous reports.31,32 The frequency of congenital malformations in this study (1.1%) was similar to that observed in a study conducted in Europe (1.5%),32 but lower than that observed in a recent study from an Italian ARV cohort (3.2%).33–35 No data on the frequency of congenital malformations in the general population of infants at birth are available in Brazil. Therefore, one can compare the rate of congenital malformations encountered in this study with the rate in the general population. However, since children were evaluated only at delivery this could have underestimated the rate in our study.

Frequency of other medical events was very low, and they seem to be more related to HIV-infection immunodeficiency than to ART use during pregnancy.

In conclusion, the overall incidence of ADR was low in women exposed to ARV during PMTCT. None of the ADR observed were unexpected and in most cases they were mild to moderate, with no fatal outcome. Discontinuation or suspension of ARV was rare. The high effectiveness of ART for PMTCT overcomes the risks of adverse drug reactions.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.