Since the beginning of the HIV burden, Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL)/HIV co-infection has been diagnosed not only in areas where VL is endemic (Latin America, India, Asia, Southern Europe), but also in North America, were it is considered an opportunistic disease. Clinical presentation, diagnostic tests sensitivity and treatment response in this population differs from VL alone.

ObjectivesTo evaluate factors related to an unfavorable outcome in patients with VL/HIV diagnosis in a reference center in northeast Brazil.

MethodsCo-infected patients, diagnosed from 2010 to 2012, were included. Data from medical records were collected until one year after VL treatment completion.

ResultsForty-two HIV-infected patients were included in the study. Anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia were present in 95%, 70.7%, and 63.4%, respectively. Mean T CD4+ (LTCD4) lymphocyte count was 183 cells/dL. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was being used by 54.7% of cases. A favorable outcome was seen in 71.4% of cases. Recurrence of VL occurred in nine patients and deaths were secondary to infectious complications (3/42 patients). Very low LTCD4 count (<100 cells/dL) was the only independent variable associated with an unfavorable outcome in multivariate analysis (p=0.03).

ConclusionLow LTCD4 count at presentation was associated with unfavorable outcome in VL/HIV patients.

Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar, is usually caused by Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi, and is characterized by fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, substantial weight loss, and hypergammaglobulinemia. Since the beginning of the HIV burden, co-infection of VL and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been diagnosed not only in areas where VL is endemic (Latin America, India, Asia, Southern Europe), but also in North America, were it is considered an opportunistic disease. In Brazil, some authors have reported 5% prevalence in the beginning of the 21st century.1 In fact, the risk of developing VL appears to be considerably higher in the HIV-infected population.2 This association raised a lot of concerns and questions. Many studies showed that clinical presentation in this population differs from VL alone.2,3 The sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic tests seems to be different as well. Parasitologic direct visualization tests are more sensitive than in the HIV negative population because of the higher parasite burden observed in VL/HIV individuals.4 Also, there is much evidence that VL/HIV patients have poorer response to treatment and higher mortality rates.5–9 These data suggest that VL/HIV co-infection should be considered an emergent disease and that efforts must be done to a better understanding of this condition.

The aim of this study was to evaluate factors that influenced the outcome in patients with VL/HIV diagnosis in a reference center in northeast Brazil.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective cohort study was conducted at Hospital São José (HSJ), a state reference center for infectious diseases in Ceará, northeast Brazil. All adult (>18 years) patients diagnosed with VL/HIV co-infection from Jan/2010 to Dec/2012 were included and data from their medical records were collected until one year after VL treatment completion. Sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory, and treatment data were abstracted. Patients were classified into two groups for comparison: favorable and unfavorable outcome. Unfavorable outcome was considered when death or VL relapse occurred. According to the study inclusion criteria, the presence of diagnostic confirmation of VL (either parasitologic or serologic – DAT, ELISA, or rK39) and HIV (serologic or PCR) infection was necessary. The HIV diagnosis was in accordance to the Brazilian HIV Diagnosis Guideline, October/2009.10 Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of HSJ (CEP/HSJ judgment no. 173.415/2012).

The statistical analysis was performed using STATA 12. Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test were used to compare means and medians of continuous variables, respectively. Some of these were categorized to allow statistical analyses. Chi-square tests were used for the two patient groups comparison in the univariate analysis. All variables with a p-value <0.20 were included in a multivariate logistic regression model. A significant association was considered with a p-value <0.05.

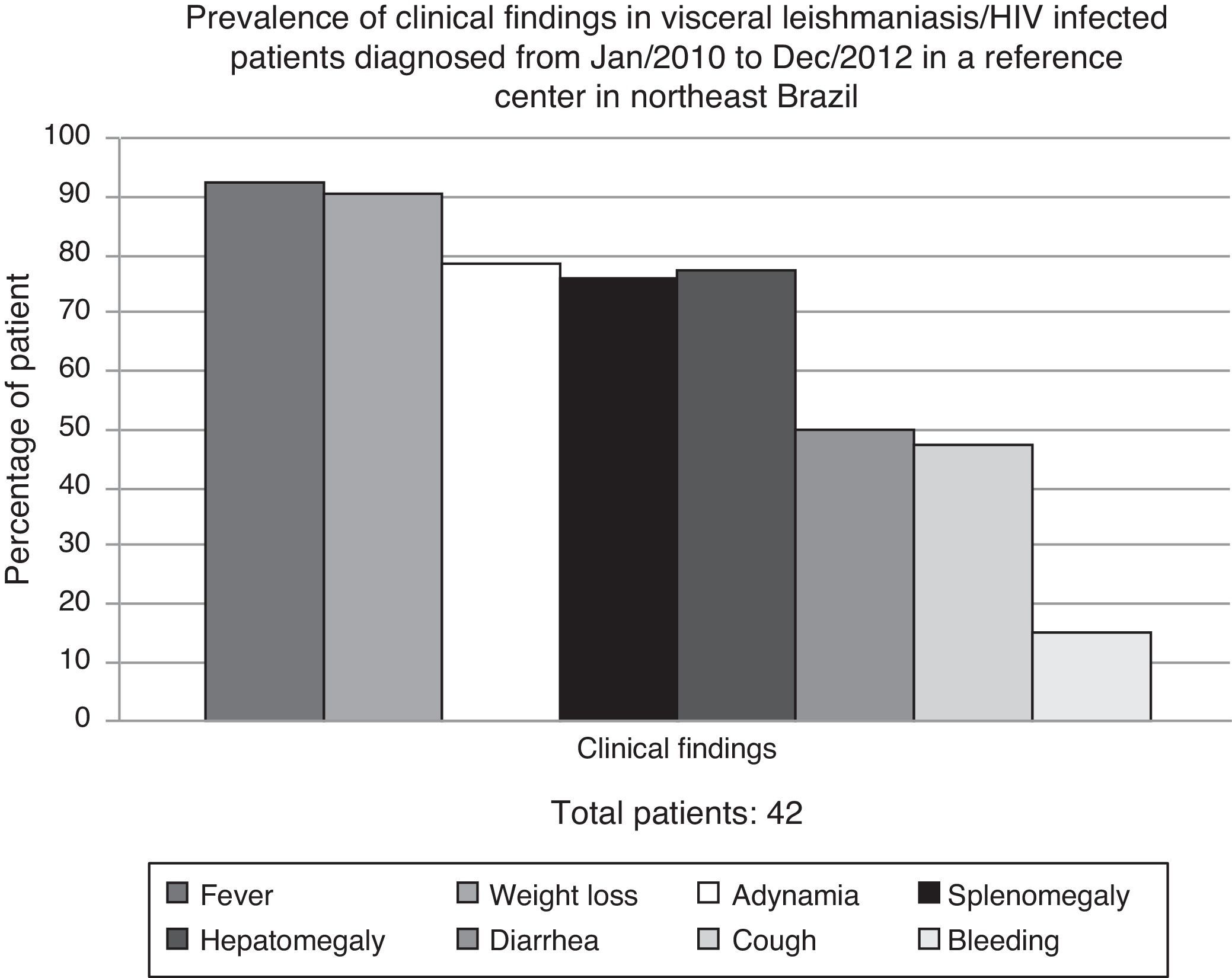

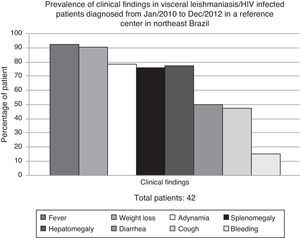

ResultsDuring the study period, 635 VL cases were diagnosed at HSJ. Forty-two (6.6%) were HIV-infected adult patients and were, therefore, included in the study. All of them had clinical VL diagnosis confirmed either by parasitologic tests (bone marrow aspiration with direct exam – 80.5%) or serologic methods (rK39 antibodies – 66.6%) from January/2010 to December/2012. In 14 patients (34%), the diagnosis was confirmed by the two methods. Patients were mainly young man (88.1% male, mean age 35 years), who lived in urban area (76%). Most of them presented with fever, weight loss, adynamia, and hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 1).

Laboratory data showed anemia in 95% (mean hemoglobin level 7.8g/dL), leukopenia in 70.7% (mean leukocytes 1756 cells/dL), and thrombocytopenia in 63.4% (mean platelets count 62,792/dL) of the patients. Abnormal levels of creatinine and albumin were also noted, although least frequently. T CD4+ (LTCD4) Lymphocyte count at VL diagnosis was low (mean LTCD4 183 cells/dL) and in 61.9% patients it was below 200 cells/dL. Viral load was detectable in 54.7% of cases, even though 73.8% were on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), with median therapy duration of 7.6 months.

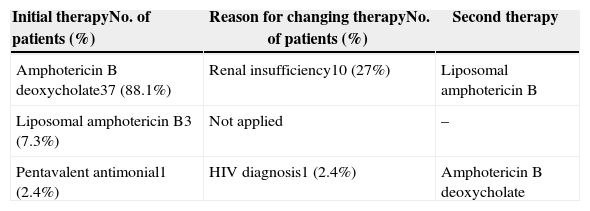

Therapy with amphotericin B deoxycholate was initiated in 88.1% of the participants; 27% were subsequently switched to the liposomal formulation due to adverse events. One of the patients died before initiating treatment and another patient initiated with pentavalent antimonial and was switched to amphotericin B deoxycholate after being diagnosed as HIV positive. Table 1 summarizes VL treatment options of the studied patients and the reasons for therapy change.

Anti-leishmania treatment in visceral leishmaniasis/HIV infected patients diagnosed from Jan/2010 to Dec/2012 in a reference center in northeast Brazil.

| Initial therapyNo. of patients (%) | Reason for changing therapyNo. of patients (%) | Second therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B deoxycholate37 (88.1%) | Renal insufficiency10 (27%) | Liposomal amphotericin B |

| Liposomal amphotericin B3 (7.3%) | Not applied | – |

| Pentavalent antimonial1 (2.4%) | HIV diagnosis1 (2.4%) | Amphotericin B deoxycholate |

A favorable outcome after one-year follow-up was seen in 71.4% of cases. Recurrence of VL was diagnosed in nine patients, with mean time to recurrence of 38 days. All deaths were secondary to infectious complications (3/42 patients). One of them had pneumonia with severe respiratory insufficiency and the others died because of septic shock.

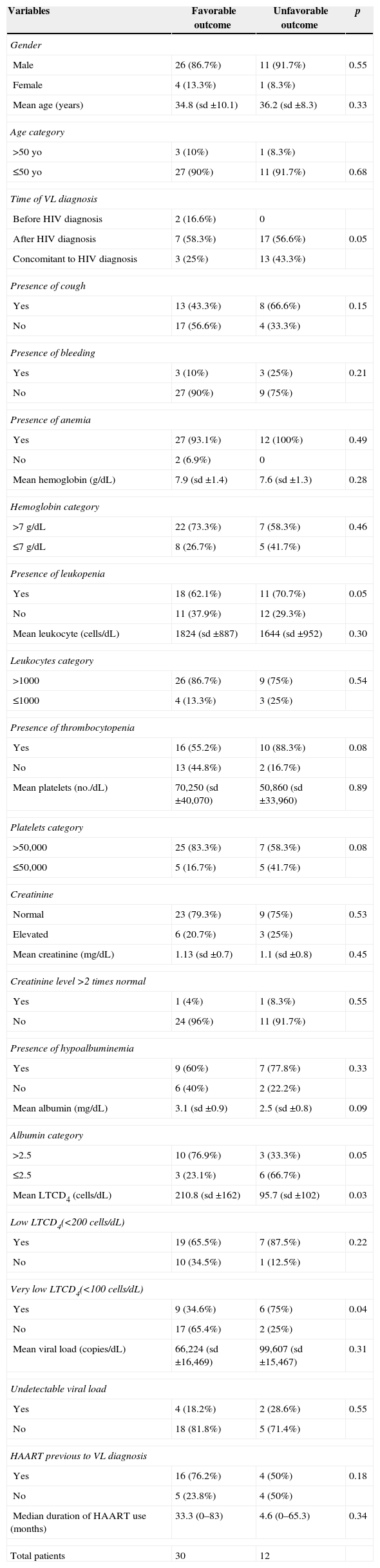

In order to identify factors that were associated with an unfavorable outcome, patients were classified into two groups. Table 2 shows univariate analysis of epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory data. The presence of very low levels of LTCD4 (<100 cells/dL) was the only variable with significant difference between the two groups (p<0.05). This variable, along with time of VL/HIV diagnosis, presence of cough, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, very low platelets count (<50,000), very low albumin level (≤2.5mg/dL), and HAART before VL diagnosis were selected for inclusion into the logistic regression model (p<0.2). Very low LTCD4 count was the only independent predictor of an unfavorable outcome in the final model (p=0.03).

Evaluation of visceral leishmaniasis/HIV co-infection outcome in patients diagnosed from Jan/2010 to Dec/2012 in a reference center in northeast Brazil – univariate analysis.

| Variables | Favorable outcome | Unfavorable outcome | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 26 (86.7%) | 11 (91.7%) | 0.55 |

| Female | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Mean age (years) | 34.8 (sd ±10.1) | 36.2 (sd ±8.3) | 0.33 |

| Age category | |||

| >50yo | 3 (10%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

| ≤50yo | 27 (90%) | 11 (91.7%) | 0.68 |

| Time of VL diagnosis | |||

| Before HIV diagnosis | 2 (16.6%) | 0 | |

| After HIV diagnosis | 7 (58.3%) | 17 (56.6%) | 0.05 |

| Concomitant to HIV diagnosis | 3 (25%) | 13 (43.3%) | |

| Presence of cough | |||

| Yes | 13 (43.3%) | 8 (66.6%) | 0.15 |

| No | 17 (56.6%) | 4 (33.3%) | |

| Presence of bleeding | |||

| Yes | 3 (10%) | 3 (25%) | 0.21 |

| No | 27 (90%) | 9 (75%) | |

| Presence of anemia | |||

| Yes | 27 (93.1%) | 12 (100%) | 0.49 |

| No | 2 (6.9%) | 0 | |

| Mean hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.9 (sd ±1.4) | 7.6 (sd ±1.3) | 0.28 |

| Hemoglobin category | |||

| >7g/dL | 22 (73.3%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0.46 |

| ≤7g/dL | 8 (26.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | |

| Presence of leukopenia | |||

| Yes | 18 (62.1%) | 11 (70.7%) | 0.05 |

| No | 11 (37.9%) | 12 (29.3%) | |

| Mean leukocyte (cells/dL) | 1824 (sd ±887) | 1644 (sd ±952) | 0.30 |

| Leukocytes category | |||

| >1000 | 26 (86.7%) | 9 (75%) | 0.54 |

| ≤1000 | 4 (13.3%) | 3 (25%) | |

| Presence of thrombocytopenia | |||

| Yes | 16 (55.2%) | 10 (88.3%) | 0.08 |

| No | 13 (44.8%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| Mean platelets (no./dL) | 70,250 (sd ±40,070) | 50,860 (sd ±33,960) | 0.89 |

| Platelets category | |||

| >50,000 | 25 (83.3%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0.08 |

| ≤50,000 | 5 (16.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | |

| Creatinine | |||

| Normal | 23 (79.3%) | 9 (75%) | 0.53 |

| Elevated | 6 (20.7%) | 3 (25%) | |

| Mean creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.13 (sd ±0.7) | 1.1 (sd ±0.8) | 0.45 |

| Creatinine level >2 times normal | |||

| Yes | 1 (4%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0.55 |

| No | 24 (96%) | 11 (91.7%) | |

| Presence of hypoalbuminemia | |||

| Yes | 9 (60%) | 7 (77.8%) | 0.33 |

| No | 6 (40%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Mean albumin (mg/dL) | 3.1 (sd ±0.9) | 2.5 (sd ±0.8) | 0.09 |

| Albumin category | |||

| >2.5 | 10 (76.9%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0.05 |

| ≤2.5 | 3 (23.1%) | 6 (66.7%) | |

| Mean LTCD4 (cells/dL) | 210.8 (sd ±162) | 95.7 (sd ±102) | 0.03 |

| Low LTCD4(<200 cells/dL) | |||

| Yes | 19 (65.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0.22 |

| No | 10 (34.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Very low LTCD4(<100 cells/dL) | |||

| Yes | 9 (34.6%) | 6 (75%) | 0.04 |

| No | 17 (65.4%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Mean viral load (copies/dL) | 66,224 (sd ±16,469) | 99,607 (sd ±15,467) | 0.31 |

| Undetectable viral load | |||

| Yes | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0.55 |

| No | 18 (81.8%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

| HAART previous to VL diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 16 (76.2%) | 4 (50%) | 0.18 |

| No | 5 (23.8%) | 4 (50%) | |

| Median duration of HAART use (months) | 33.3 (0–83) | 4.6 (0–65.3) | 0.34 |

| Total patients | 30 | 12 | |

From Jan/2010 to Dec/2012, 1650 VL cases were confirmed in the state of Ceará11; 635 (38.4%) were diagnosed in HSJ. This data shows the importance of HSJ as a reference center for the diagnosis of this disease in our state. However, the prevalence of VL-HIV co-infection among VL patients diagnosed in HSJ was slightly higher (6.6%) than data shown in other Brazilian studies. Botelho et al. reported a prevalence of 5% of this co-infection among VL confirmed cases, while another group showed an even lower prevalence (1.1%).1,12 In both studies data were collected from governmental disease notification database, which gathers information from a variety of healthcare facilities. HSJ, in contrast, is an infectious disease reference center and, therefore, concentrate not only VL but also the HIV infection cases in the state. This could explain this higher prevalence shown in our study.

Most of the participants had their VL diagnosis confirmed with parasitologic tests, with only 66% showing positive serologic exams. Deniau et al. and Cota et al. observed similar results with 60% and 54% positive serologic tests, respectively, in VL/HIV infected individuals. These findings suggest that parasitologic diagnostic methods should be preferred in this specific population.13,14

Most of the cases were from urban areas. This is consistent with the trend toward VL urbanization observed in many countries, including Brazil. This urbanization process has been noted since the end of the ninetieth decade. Poverty and scarce raining seasons leading to intense internal migration from rural to urban areas are important factors that may explain this occurrence.15–18

Although some authors have shown atypical clinical presentation in VL/HIV patients,2,3,14,18,19 manifestations at unusual sites such as skin, lungs, and the gastrointestinal tract were not observed in our study. Classical symptoms (fever, weight loss, and hepatosplenomegaly) were more prevalent; a result also found in other Brazilian series.6,20

Even though our study sample consisted of only VL/HIV co-infected patients, both mean hemoglobin (7.8g/dL) and platelets levels (62,792/dL) were similar to those found in published series describing HIV negative VL cases. In large series of patients with VL from India, average hemoglobin level varied from 7.8 to 8.3g/dL, and mean platelet count was 109,000 (±82.3). Mean leukocyte level varied from 2.8×103/L to 4×103/L, which was higher than the value found in our study.21 VL pancytopenia has been well studied. The cause of anemia is probably multifactorial: immune-mediated mechanism, alteration of red blood cells membrane permeability, hemolysis, and hypersplenism. The former is possibly the main explanation for low leukocyte and platelet counts.22 In the HIV population, Leishmaniasis promotes an increase in HIV load leading to more rapid decrease in LTCD4 cell count and progression to AIDS. This finding and other factors related to the virus itself can play an important role in more severe leukopenia in this co-infected population.7

Mean LTCD4 count at VL presentation varies widely in published data, although most patients have profound immunosuppression, usually with LTCD4 counts below 200 cells/dL and up to half of cases with less than 100 cells/dL.5,6,23,24 In our study, 61.9% of the participants had below 200 cells/dL but only 44% had very low LTCD4 counts (<100 cells/dL). This could be due to the high frequency of HAART use (73.8%), even though incomplete adherence was found in some cases.

Amphotericin B deoxycholate was the drug of choice in 88.1% of patients and only 7.3% had their treatment initiated with the liposomal formulation. This finding is in accordance with the Brazilian Ministry of Health recommendation at that time.12 This guideline was modified in September 2013 based on plenty of evidence demonstrating the benefits of the liposomal formulation over other drug therapies. Since that time, liposomal amphotericin B is the drug of choice for the treatment of VL/HIV patients in Brazil.25

HIV infection was frequently associated with a poor outcome in VL series from India, Brazil, and Ethiopia. Mortality rates are usually higher than in the HIV negative cases (8.7–23% versus 1–5%).5,8,14,26,27 In our series the mortality rate for the co-infected patients was 7.1%. This intermediate value was below the usually expected rate but still higher than the mortality rate seen in HIV negative cases.

Almost 29% of patients had an unfavorable outcome. Very low LTCD4 count (<100 cells/dL) at presentation was the only variable related to death/relapse. Other authors also found this association.7,14,23 In one study from Ethiopia, a higher risk of relapse was demonstrated even with LTCD4 counts between 100 and 200 cells/dL.28 The severe immunosuppression state may explain the frequent relapses and VL associated complications. Persistence of the parasite in lymphoid tissue is a consequence of inability to control Leishmania replication through LTCD4 mediated cellular response. Treating VL patients with anti-leishmanial therapy is associated with recovery of lymphopoietic tissue functions.29 However, in HIV-infected individuals this reconstitution is not always the case and, indeed, relapses have been described even when LTCD4 counts were above 200 cells/dL.6,28 These features are in accordance with the findings of Berenguer et al. who reported a lower risk of VL relapse only when LTCD4 counts were above 350 cells/dL.30 Despite the decrease in relapse risk with HAART use, many authors have reported that it appears to be only partially protective, suggesting that the actual goal should be to achieve the highest levels of LTCD4 possible.6,7,28

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that low LTCD4 level at presentation was associated with unfavorable outcome in VL/HIV co-infected patients. Besides all the questions raised about factors associated with mortality and relapse in this population, the initiation of HAART as early as possible seems to be a reasonable measure to reduce complications. Also, a better understanding of this emergent concurrent infection is extremely important to guide adequate management of the co-infected patients and achievement of lower relapse and death rates.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank clinical staff of Hospital São José HIV.