The aim of the present study was to determine the Chlamydia trachomatis prevalence and to identify the demographic, behavioural and clinical factors associated with C. trachomatis in human immunodeficiency virus infected men.

StudyThis was a cross-sectional study of C. trachomatis prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus-infected men enrolled at the Outpatient clinic of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome of the Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado in Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. C. trachomatis deoxyribonucleic acid from urethral samples was purified and submitted to real time polymerase chain reaction to identify the presence of C. trachomatis.

ResultsA total of 276 human immunodeficiency virus-infected men were included in the study. The prevalence of C. trachomatis infection was 12% (95% confidence interval 8.1%–15.7%). The mean age of the participants was 34.63 (standard deviation 10.80) years. Of the 276 human immunodeficiency virus-infected men, 93 (56.2%) had more than one sexual partner in the past year and 105 (38.0%) reported having their first sexual intercourse under the age of 15 years. Men having sex with men and bisexuals amounted to 61.2% of the studied population. A total of 71.7% had received human immunodeficiency virus diagnosis in the last three years and 55.1% were using antiretroviral therapy. Factors associated with C. trachomatis infection in the logistic model were being single (p<0.034), men having sex with men (p<0.021), and having previous sexually transmitted diseases (p<0.001).

ConclusionThe high prevalence of C. trachomatis infection among human immunodeficiency virus-infected men highlights that screening human immunodeficiency virus-infected men for C. trachomatis, especially among men having sex with men, is paramount to control the spread of C. trachomatis infection.

Genital Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) infection, the most prevalent sexually transmitted disease (STDs) in the world, is a major public health problem.1,2 Asymptomatic infections are common and are associated with high probability of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.3–5 The screening of HIV-infected individuals for CT is a key strategy for reducing the transmission of HIV.2,3 Few studies have been conducted on CT infection among men in Brazil.6 A study in HIV-negative men attending STDs clinics have estimated the incidence of urethral CT infection to be 13.1%.7 Studies conducted in HIV-infected men outside of Brazil have reported prevalence rates of 9%8 and 2–10% in HIV-infected men and in men who have sex with men (MSM),2,9 respectively.

There is no mandatory reporting system for CT infections in Brazil,8 and the lack of population-based studies in HIV-infected patients hinders efforts to document the problem, implement priority interventions and evaluate their efficacy. Screening for CT infection in HIV-infected individuals is important for monitoring STDs and for elaborating preventive measures as well as treatment assistance to this population.

The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of CT infection and associated risk factors in HIV-infected men followed in a referral hospital specializing in infectious and tropical diseases in Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil.

MethodsA population based cross-sectional study among HIV-infected men was conducted at the referral hospital of the Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado (FMT-HVD) in Manaus, capital city of the state of the Amazonas, Brazil from November 1, 2009 to November 1, 2010. HIV-infected men were invited to participate in the study by signing an informed consent form as approved by the ethical committee of the FMT-HVD. Each participant answered a questionnaire concerning socio-demographic factors, age of first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners over the past 12 months, regular use of condoms, sexual behaviours, prior symptoms of STDs. Signs and symptoms of STD on physical examination were also recorded and adequate treatment was provided.

The inclusion criteria were the following: male individuals with positive serology for HIV 1–2, sexually active, over 18 years of age and agreed to a urethral sample collection. Vulnerable male patients (mental diseases and younger than 18 years old) were excluded from the study.

The sample size was calculated for estimating the prevalence of CT infection in Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) people with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a bilateral size of 0.5%. The sample size was calculated based on an average rate of 6.0% with a variation of ±3.0% which generated a number of 270 patients. Assuming a loss of 10%, the final sample size was 297 patients. Of note, the FMT-HVD is the referral centre for AIDS and all the patients with HIV/AIDS from the state of Amazonas are referred to that centre. An average of 310 HIV-infected men is treated yearly from 2001 to 2010 at the FMT-HVD and in the year 2010, a total of 530 HIV-infected men were enrolled.

Urethral samples were collected by inserting a small brush (Cavi-brush) in the distal urethra, between 1.5 and 2cm, and rotating it five times clockwise. The samples were then placed in tubes containing 400μL of buffer solution (10mM Tris–HCL and 1mM EDTA) and kept on ice until they were transported to the laboratory, where they were stored at −20°C until processing for deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) purification. DNA purification was performed using the commercial DNA extraction kit Nucleo-Spin Tissue – Machery – NagelTM following the company's instructions. For the detection of CT DNA by RT-PCR, the following pair of primers amplifying a fragment of 241 base pairs CT plasmid DNA was used: KL1 5′-TCCGGAGCGAGTTACGAAGA-3′ and KL 2′-AATCAATGCCCGGGATTGGT-3′. Briefly, 5μL of DNA sample and 3μL of each primer (10pmol/μL) were added to a final volume of 25μL containing 12.5μL of Maxima® SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (2×). For the initial confirmation of the amplicon size the PCR product was electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gel and revealed with ethidium bromide under UV. Furthermore, sample was considered positive when RT-PCR analysis showed unique peak dissociation curve at 78°C.

The data were stored and analyzed using the Epi Info software, version 3.5.2, and the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 16.0 for Windows. Chi-square test with Yates correction was used to assess for possible associations between clinical, demographic or risk behaviours variables and CT infection. Fisher exact test was applied when appropriate. The odds ratio along with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated for variables to estimate the degree of association between CT infection and potential risk factors. The multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied to examine the independent effect of each demographic, clinical or risk behaviour variables on CT infection, controlling for all other variables simultaneously. All variables that were moderately associated with a significance of p≤0.15 in the univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariate model. In the final model analysis, only those variables that remained significant with p<0.05 were considered.

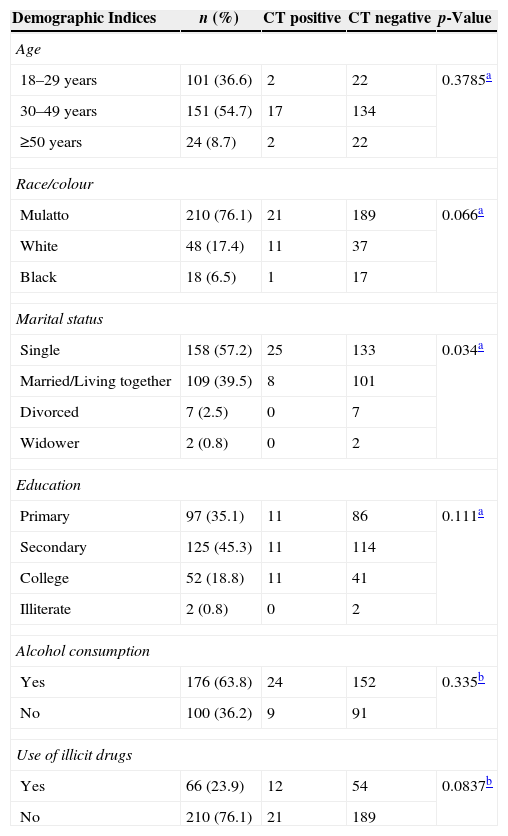

ResultsOf a total of 276 HIV-infected men included in the study, 33 were infected with CT infection showing a prevalence of 12% (95% CI 8.1%–15.7%). No urethral symptoms were observed in any of the HIV-infected men. Baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 34.6 years (SD=10.8) and 36.6% were 29 years old or less. More than 80% of the 276 HIV-infected men had up to 11 years of schooling. A total of 63.8% reported alcohol use and 23.9% illicit drugs abuse.

Prevalence of CT infection (RT-PCR) and its association with socio-demographic factors among 276 HIV-infected men treated at the FMT-HVD, 2009–2010.

| Demographic Indices | n (%) | CT positive | CT negative | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 years | 101 (36.6) | 2 | 22 | 0.3785a |

| 30–49 years | 151 (54.7) | 17 | 134 | |

| ≥50 years | 24 (8.7) | 2 | 22 | |

| Race/colour | ||||

| Mulatto | 210 (76.1) | 21 | 189 | 0.066a |

| White | 48 (17.4) | 11 | 37 | |

| Black | 18 (6.5) | 1 | 17 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 158 (57.2) | 25 | 133 | 0.034a |

| Married/Living together | 109 (39.5) | 8 | 101 | |

| Divorced | 7 (2.5) | 0 | 7 | |

| Widower | 2 (0.8) | 0 | 2 | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 97 (35.1) | 11 | 86 | 0.111a |

| Secondary | 125 (45.3) | 11 | 114 | |

| College | 52 (18.8) | 11 | 41 | |

| Illiterate | 2 (0.8) | 0 | 2 | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Yes | 176 (63.8) | 24 | 152 | 0.335b |

| No | 100 (36.2) | 9 | 91 | |

| Use of illicit drugs | ||||

| Yes | 66 (23.9) | 12 | 54 | 0.0837b |

| No | 210 (76.1) | 21 | 189 | |

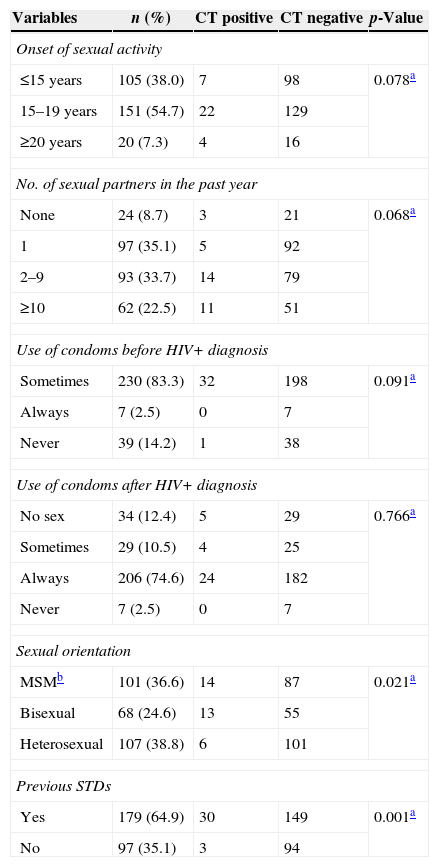

Concerning risk behaviours, as shown in Table 2, 93 (56.2%) participants reported having more than one sexual partner in the past year, and 105 (38.0%) had their first sexual intercourse under the age of 15 years. Prior to the diagnosis of HIV infection, 230 (83.3%) patients admitted irregular use of condoms. After the diagnosis, 206 (74.6%) reported always using condoms. However, 179 (64.9%) subjects reported having previous STDs. A history of STDs was strongly associated (p<0.001) with the detection of CT. Regarding sexual orientation, homosexuals and bisexuals together made up to 61.2% of the studied population. Multivariate logistic regression showed that MSM [OR=2.51 (95% CI 1.12–6.64) and previous STD [OR=3.46 (95% CI 1.96–5.72) were independent risk factors for CT infection among HIV-infected men.

Sexual behaviours of 276 patients with HIV+/AIDS sorted by CT urethral infection status as detected by PCR.

| Variables | n (%) | CT positive | CT negative | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of sexual activity | ||||

| ≤15 years | 105 (38.0) | 7 | 98 | 0.078a |

| 15–19 years | 151 (54.7) | 22 | 129 | |

| ≥20 years | 20 (7.3) | 4 | 16 | |

| No. of sexual partners in the past year | ||||

| None | 24 (8.7) | 3 | 21 | 0.068a |

| 1 | 97 (35.1) | 5 | 92 | |

| 2–9 | 93 (33.7) | 14 | 79 | |

| ≥10 | 62 (22.5) | 11 | 51 | |

| Use of condoms before HIV+ diagnosis | ||||

| Sometimes | 230 (83.3) | 32 | 198 | 0.091a |

| Always | 7 (2.5) | 0 | 7 | |

| Never | 39 (14.2) | 1 | 38 | |

| Use of condoms after HIV+ diagnosis | ||||

| No sex | 34 (12.4) | 5 | 29 | 0.766a |

| Sometimes | 29 (10.5) | 4 | 25 | |

| Always | 206 (74.6) | 24 | 182 | |

| Never | 7 (2.5) | 0 | 7 | |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| MSMb | 101 (36.6) | 14 | 87 | 0.021a |

| Bisexual | 68 (24.6) | 13 | 55 | |

| Heterosexual | 107 (38.8) | 6 | 101 | |

| Previous STDs | ||||

| Yes | 179 (64.9) | 30 | 149 | 0.001a |

| No | 97 (35.1) | 3 | 94 | |

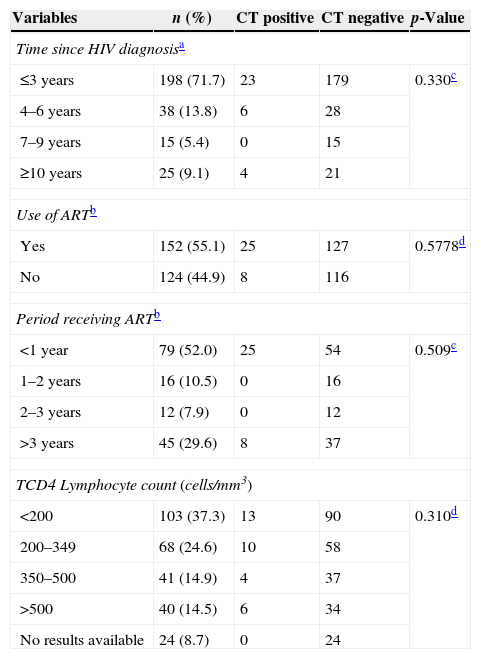

Table 3 shows variables related to HIV status. None of the variables studied showed any association with CT infection. A total of 71.7% had received the HIV diagnosis in the last three years and 55.1% were using antiretroviral therapy.

Variables associated with the presence of HIV among 276 patients sorted by CT urethral infection status as detected by PCR.

| Variables | n (%) | CT positive | CT negative | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time since HIV diagnosisa | ||||

| ≤3 years | 198 (71.7) | 23 | 179 | 0.330c |

| 4–6 years | 38 (13.8) | 6 | 28 | |

| 7–9 years | 15 (5.4) | 0 | 15 | |

| ≥10 years | 25 (9.1) | 4 | 21 | |

| Use of ARTb | ||||

| Yes | 152 (55.1) | 25 | 127 | 0.5778d |

| No | 124 (44.9) | 8 | 116 | |

| Period receiving ARTb | ||||

| <1 year | 79 (52.0) | 25 | 54 | 0.509c |

| 1–2 years | 16 (10.5) | 0 | 16 | |

| 2–3 years | 12 (7.9) | 0 | 12 | |

| >3 years | 45 (29.6) | 8 | 37 | |

| TCD4 Lymphocyte count (cells/mm3) | ||||

| <200 | 103 (37.3) | 13 | 90 | 0.310d |

| 200–349 | 68 (24.6) | 10 | 58 | |

| 350–500 | 41 (14.9) | 4 | 37 | |

| >500 | 40 (14.5) | 6 | 34 | |

| No results available | 24 (8.7) | 0 | 24 | |

Our study prospectively investigated CT infection among HIV-infected men in the Amazonas through the RT-PCR technology to provide a rapid diagnosis for improving management of patients so as to limit the spread of CT. In Brazil, limited data are available demonstrating the precise pattern of the epidemiological behaviour of CT infection in men,6,10 and the status of this infection within the population of HIV-infected men is unknown.

The prevalence of CT urethral infection in HIV-infected men observed in this study was 12%. The observed prevalence is similar to that observed in non-HIV-infected men receiving care at six STD clinics in Brazil,6 and in HIV-infected men in United Kingdom and USA.8,11

STDs are of primary importance because of the emergence of AIDS. These infections enhance the sexual transmission of HIV3,12,13 and are associated with earlier and more severe symptoms in HIV-infected individuals.14–16 Furthermore, they can cause serious complications, resulting in chronic diseases and even death. Infections in men often cause problems in the genitourinary tract that can result in male infertility. In women, the consequences can be extremely severe, including chronic pelvic pain, infertility, and cervical cancer.16,17

None of the HIV-infected men with CT infection in this study showed any urethral symptoms, which is consistent with most previous studies. A high proportion of asymptomatic patients has been observed in CT infections18 indicating a need for screening in this population.11,19–21 The routine testing of patients remains a controversial issue, given that some studies show a higher prevalence of CT infection among individuals with urethral symptoms.8,19,22–24

Several studies have reported higher prevalence of CT infection in young individuals (<25 years of age),23 but it was not observed in this study. Similar to work previously published by Iwuji et al. in 2008 in the United Kingdom,8 other studies have reported common associations between CT infections and reports of multiple partners, irregular use of condoms and a history of STDs.25,26 Here, only a history of STDs was found to be associated with CT infection. Notably, Fioravante et al.25 observed a prevalence of 5% of chlamydial infection among male asymptomatic conscripts. This may reflect the prevalence in the general population of male Brazilians, which is lower than the prevalence in HIV-infected men.

A significant association between CT urethral infection and sexual orientation (MSM) was noted in this study. Several studies have demonstrated that a high prevalence of STDs,9,27 bacterial STDs,14 anorectal CT,22–24,28 and CT urethral infection14,28 are directly related to the sexual behaviour of MSM.

The possibility of response bias may be a limitation in this study due to the tendency to provide socially acceptable answers. However, such biases would result in underestimation of risk attitudes and behaviours. Inaccuracies of recall of condom use, age of first intercourse, and number of sexual partners may also have occurred. Another limitation is probably few HIV-infected individuals coming from high socioeconomic classes who may seek private clinics for treatment and thus potentially introducing patient selection bias. However, as treatment delivered for free in public hospitals in Brazil compared to the expensive cost in private hospitals, selection bias may have been negligible.

The findings from this study have important implications for education and prevention efforts directed towards young HIV-infected men, mainly MSM. A comprehensive approach would promote sexual responsibility and, at the same time, improve young men's understanding of sexual health risks to curb the spread of CT infection.

The lack of clinical symptoms in CT infection impairs the identification of infected individuals. This study underscores the need for screening through laboratorial tests to identify these individuals for rapid treatment, to limit the spread and also to avoid chronic symptoms and severe consequences for the individual. This topic is of extreme importance for health policies, as it has a significant impact on family policy and has consequences for the sexual and reproductive health of both the population in general and, more specifically, the HIV-infected population.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We acknowledge the contributions of Dra. Heline Silva Lira, Dra. Carolina Marinho da Costa, Dra. Marly Marquez de Melo and Technician Elizabeth Monteiro for performing laboratory procedures.

Sources of support: Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado.