To describe the pain in patients infected with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1, clinically and epidemiologically.

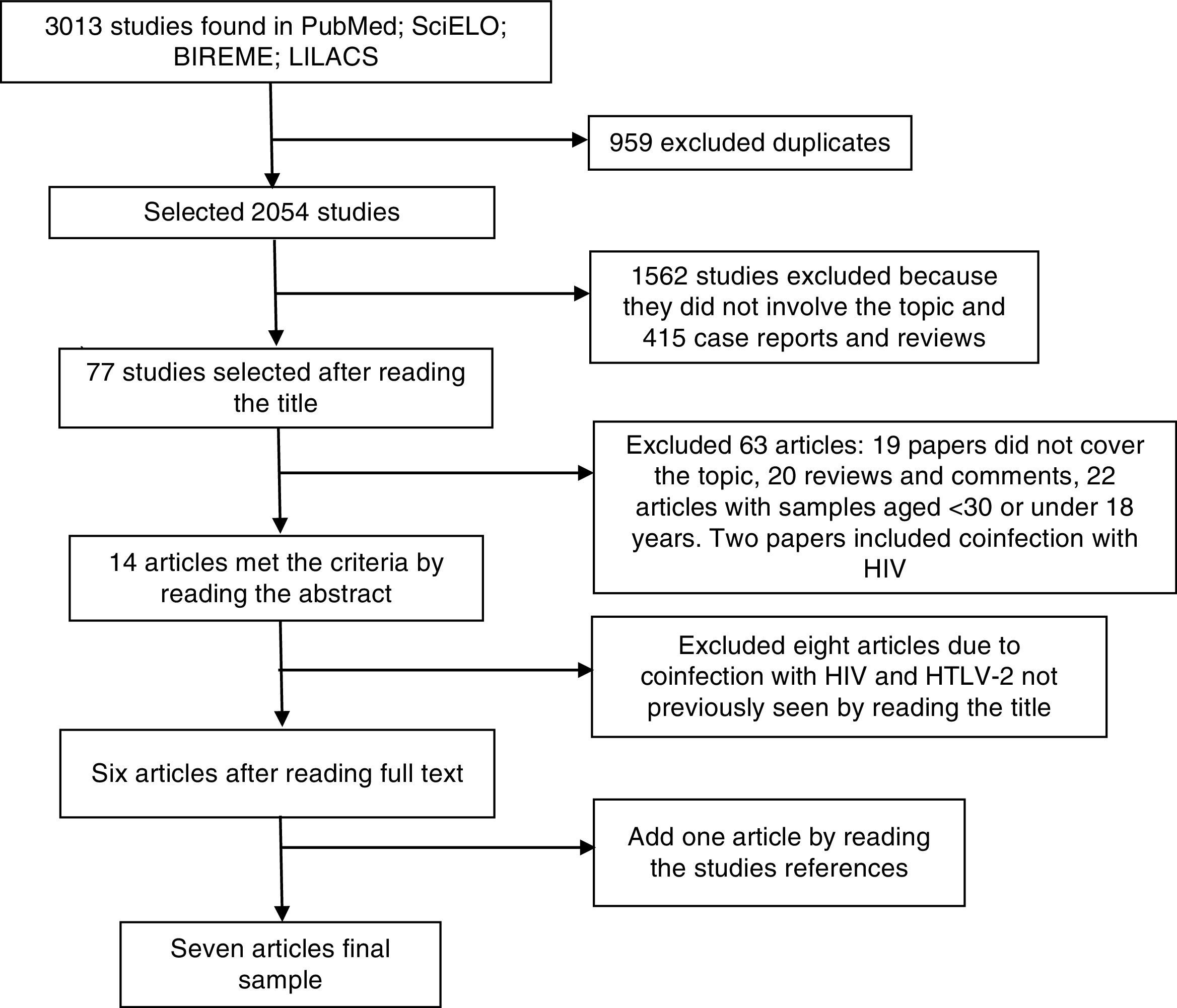

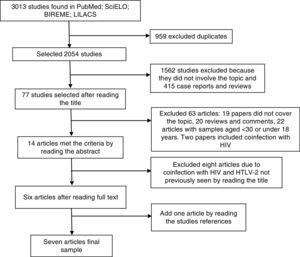

MethodsThis systematic review was based on The PRISMA Statement. Four reviewers searched PUBMED, SciELO, LILACS and BIREME for data from observational studies and clinical trials (n≥30) regarding pain prevalence, characteristics, and associated factors in patients with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1. No limits on publication date or language were established. Studies that did not have pain as an outcome measure or not involving human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infected patients were excluded.

ResultsA total of 3013 articles (including duplicates) were found of which seven met the predetermined criteria. The most common pain region was the lower back (53.0%). Non-neuropathic type (ranging from 52.6% to 86.8%) was more frequent in human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis participants, and neuropathic pain was more common in human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 carriers (53.1%). The pain was mostly reported as moderate or severe. One study showed that chronic pain was negatively associated with quality of life.

DiscussionPain is a common complaint in human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infected patients, with lower back pain as the most frequent site. Pain can either be nociceptive, neuropathic, or both, is frequently severe, and negatively affects quality of life. Only studies of two countries were included in this review, limiting the external validity of the conclusions. The heterogeneity of variables prevented us from implementing a meta-analysis. Further research should better characterize the pain and explore its impact on quality of life, especially using longitudinal study design.

The human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is a retrovirus that can be transmitted by sexual contact, shared needles and syringes, blood transfusions, through the placenta, or during breastfeeding.1,2 The prevalence of HTLV-1 is still unknown, although it is estimated that 10–20 million people worldwide carry the virus.1

The chance of an infected asymptomatic individual to develop HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) ranges between 1 and 5%.3 The prevalence is higher in the Caribbean and South American countries (4%) than in Japan (0.25%). The average prevalence is 2% in Latin America. Therefore, it is estimated that 100,000 cases of HAM/TSP exist worldwide, making this spectrum of HTLV-1 a public health concern in this part of the world.4,5

Nociceptive pain (resulting from inflammatory mediators) and neuropathic pain (secondary from injury and/or dysfunction of the somatosensory system) are frequent, as well as other sensory disturbances.4,6 There are also reports of an association between HTLV-1 infection and rheumatic diseases such as Sjogren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia.7

Although many studies attempted to characterize pain in HTLV-1 infected patients,8–12 it is not clear whether it is a focal manifestation of the neurological complex or a systemic disease, such as other diffuse pain syndromes. To answer these questions, it is important to clarify some relevant issues that remain unclear, such as general prevalence/frequency, the affected sites, associated factors and the most frequent nature of pain (neuropathic or nociceptive) in this disabling condition. The goal of this study was to review the literature regarding pain characteristics and associated factors in patients with HTLV-1.

Materials and methodsThis systematic review was based on the PRISMA Statement for reporting systematic reviews and metanalyses. Four independent reviewers searched PubMed, SciELO, BIREME and LILACS. The search was conducted from October 2014 until January 2016. The search strategy is described in Appendix A.

This review included cross-sectional and cohort studies, in addition to baseline data from clinical trials when it was feasible to extract information regarding pain prevalence and associated factors in HTLV-1 infected patients. No language or publication date restrictions were imposed. The studies had to involve more than 30 participants, aged more than 18 years old, with a clear definition of HTLV-1 or HAM/TSP diagnostic criteria. Other study designs, studies not involving pain as an outcome measure, inclusion of other infections such as human immunodeficiency virus or HTLV-2, and studies involving other neurological diseases were excluded.

Articles were first screened by title, and then by abstract. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were read and eligibility criteria were applied. Disagreement about the inclusion or exclusion of a certain study were resolved by consensus meeting. Data collected from each paper included: (a) pain prevalence in HTLV-1 infected participants; (b) clinical pain description; (c) age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and educational level; and (d) number of participants. Risk of bias focused on specifications of how many participants were lost to follow up, and whether the authors had a conflict of interest.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)13 was used to assess the quality of the included studies, according to their basic designs. The scale includes three domains, with a maximum score (stars) for each of them. The domain of selection (maximum of 5 stars) includes the representativeness of the sample, sample size, non-respondents, and ascertainment of the exposure. The domain of comparability (maximum of 2 stars) includes the comparability between the groups. The outcome domain (3 stars) includes the assessment of the outcome and the statistical test. This scale classifies the articles from one star (low quality) to 10 stars (high quality). The maximum punctuation changes according to each study design (nine points for cohort and case-control studies and 10 points for cross-sectional studies).

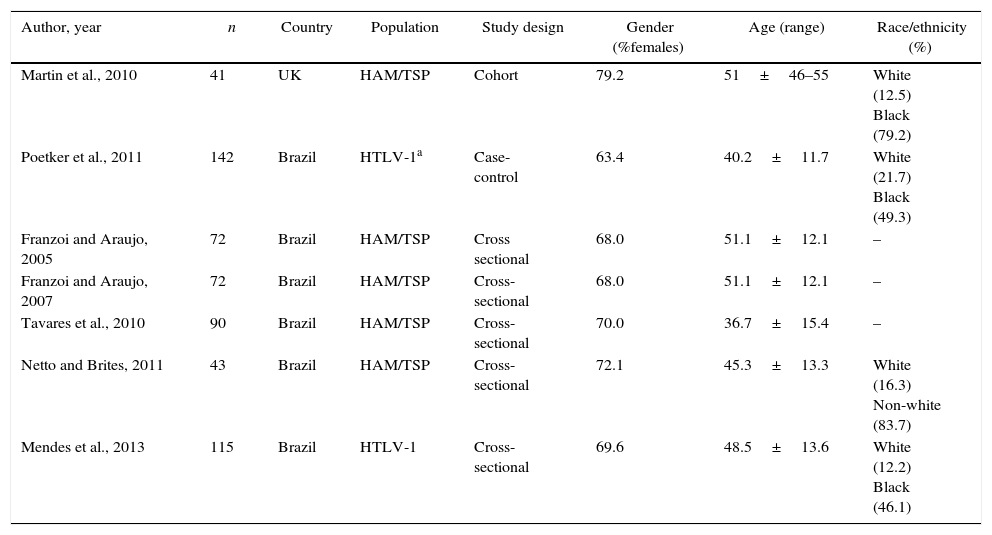

ResultsThe database search yielded 3013 citations, until January 2016, including duplicates (Fig. 1). Seven studies met the predetermined criteria1,6,8–12: six studies were identified from the database search and one study was found after a manual search (Table 1). These studies were published between 2005 and 2013. No clinical trial was included in this review. The total number of participants was 575. Approximately 70% of the included subjects were women, mean age ranging from 40 to 51 years, most of them classified as non-white (Table 1), and from a low socioeconomic and educational status.8–10

Demographic characteristics of subjects of the included studies.

| Author, year | n | Country | Population | Study design | Gender (%females) | Age (range) | Race/ethnicity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin et al., 2010 | 41 | UK | HAM/TSP | Cohort | 79.2 | 51±46–55 | White (12.5) Black (79.2) |

| Poetker et al., 2011 | 142 | Brazil | HTLV-1a | Case-control | 63.4 | 40.2±11.7 | White (21.7) Black (49.3) |

| Franzoi and Araujo, 2005 | 72 | Brazil | HAM/TSP | Cross sectional | 68.0 | 51.1±12.1 | – |

| Franzoi and Araujo, 2007 | 72 | Brazil | HAM/TSP | Cross-sectional | 68.0 | 51.1±12.1 | – |

| Tavares et al., 2010 | 90 | Brazil | HAM/TSP | Cross-sectional | 70.0 | 36.7±15.4 | – |

| Netto and Brites, 2011 | 43 | Brazil | HAM/TSP | Cross-sectional | 72.1 | 45.3±13.3 | White (16.3) Non-white (83.7) |

| Mendes et al., 2013 | 115 | Brazil | HTLV-1 | Cross-sectional | 69.6 | 48.5±13.6 | White (12.2) Black (46.1) |

n, number of participants; UK, United Kingdom; HTLV-1, human T lymphotropic virus-1; HAM/TSP, HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis.

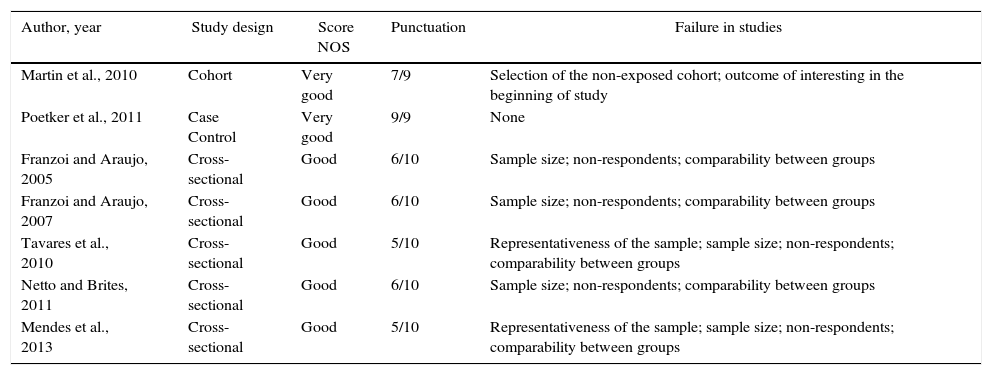

All participants were recruited at HTLV-1 reference centers and were diagnosed according to basic procedures including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction and Western blot confirmation.1,6,8–12 The World Health Organization's (WHO) guideline was used to identify HAM/TSP in six studies (F. Martin, MD, PhD, unpublished data, July, 2015).1,6,8,10–12 Two studies also used De Castro-Costa classification.8,10 One paper did not include HAM/TSP participants.9 According to the NOS, three papers were classified as of good or very good quality, and four were unsatisfactory (Table 3).

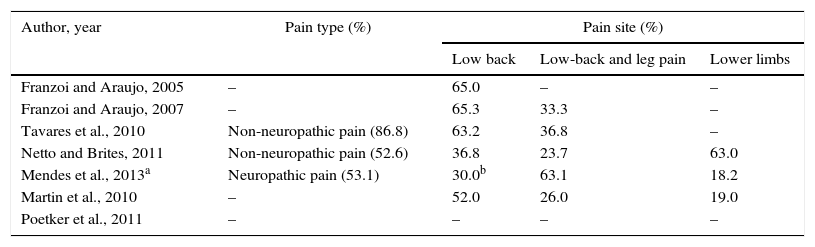

Pain prevalence ranged from 35.3% to 88.4% in the studies.1,6,8–12 Two studies tried to identify an association between pain and sociodemographic characteristics, but did not find any predictors for the development of pain.8,10 The most frequent pain sites were the lumbar region and the lower limbs (Table 2). Lower back pain was considered the worst pain site, had a negative impact on the Bodily Pain Domain of short-form (SF-36) and was described as tiring (54.3%) and sickening (50.0%) by HAM/TSP participants.11 The prevalence of pain in other body regions was less frequently reported, but included arthralgia (35.3%),9 upper limbs (25.5%),8 eyes (23.9%),9 head, face and neck (7.2%), thorax and abdominal regions (4.1%).8

Pain sites and type of subjects in the included studies.

| Author, year | Pain type (%) | Pain site (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low back | Low-back and leg pain | Lower limbs | ||

| Franzoi and Araujo, 2005 | – | 65.0 | – | – |

| Franzoi and Araujo, 2007 | – | 65.3 | 33.3 | – |

| Tavares et al., 2010 | Non-neuropathic pain (86.8) | 63.2 | 36.8 | – |

| Netto and Brites, 2011 | Non-neuropathic pain (52.6) | 36.8 | 23.7 | 63.0 |

| Mendes et al., 2013a | Neuropathic pain (53.1) | 30.0b | 63.1 | 18.2 |

| Martin et al., 2010 | – | 52.0 | 26.0 | 19.0 |

| Poetker et al., 2011 | – | – | – | – |

(–), the study did not include the pain site or type in its result.

Quality assessment of studies according to Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

| Author, year | Study design | Score NOS | Punctuation | Failure in studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin et al., 2010 | Cohort | Very good | 7/9 | Selection of the non-exposed cohort; outcome of interesting in the beginning of study |

| Poetker et al., 2011 | Case Control | Very good | 9/9 | None |

| Franzoi and Araujo, 2005 | Cross-sectional | Good | 6/10 | Sample size; non-respondents; comparability between groups |

| Franzoi and Araujo, 2007 | Cross-sectional | Good | 6/10 | Sample size; non-respondents; comparability between groups |

| Tavares et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | Good | 5/10 | Representativeness of the sample; sample size; non-respondents; comparability between groups |

| Netto and Brites, 2011 | Cross-sectional | Good | 6/10 | Sample size; non-respondents; comparability between groups |

| Mendes et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | Good | 5/10 | Representativeness of the sample; sample size; non-respondents; comparability between groups |

NOS, Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

One study distinguished chronic from acute pain and defined chronic as any pain sustained for a minimum of three months. In this study, all HAM/TSP individuals suffered chronic pain and had a longer duration of the disease. Participants who were followed up for more than two years reported the presence of pain more persistently.10 In a 15-year longitudinal study, 30.0% had become pain free while 25% of previously pain free participants reported pain. At presentation and throughout follow-up pain was more commonly persistent than intermittent.12

In three articles, the terms non-neuropathic, nociceptive, neuropathic and mixed (both neuropathic and nociceptive pain) classified the pain origin. In these cases, the Neuropathic Pain 4 Diagnostic Questionnaire (DN4)14 was used as the screening tool.8,10,11 One study found that neuropathic pain was more common in HTLV-1 carriers irrespective of the presence of HAM/TSP.8 Other studies assessed only HAM/TSP participants diagnosed according to WHO criteria, and found non-neuropathic pain was the most prevalent type (Table 2).10,11 The presence of neuropathic pain, according to one study, was associated with a higher prevalence of disability.10

Pain intensity often ranged from moderate to severe in HAM/TSP participants.10–12 Only one study assessed pain intensity in HTLV-1 carriers, and found that 94.0% had moderate or severe pain irrespective of the body region. Neuropathic pain was reported as more intense than nociceptive pain.8

One study found no difference among HAM/TSP participants with and without pain using the Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and the Osame Scale to assess the impact of the disease. It also described that chronic pain was associated with a negative impact on SF-36 Quality of Life (QoL), and was worse when present in more than one body region.10

In another study, the most frequent aggravating factor was movement, although cold weather, remaining in a same position for a long period of time, and physical efforts were also reported. Drugs and resting were the most frequent factors reported to relieve pain. This study also found that analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID), and tricyclic antidepressants were the most frequently used drugs for relieving pain.11

DiscussionThis paper represents the first study to summarize pain characteristics in HTLV-1 infected subjects. Our results show that pain is frequent and affects predominantly the lumbar region ranging from moderate to intense. It was also found that there is a larger prevalence of non-neuropathic pain in HAM/TSP, while neuropathic pain is more frequent in HTLV-1 carriers irrespective of the presence of HAM/TSP. Pain was most often chronic and affected quality of life, but data about its impact on disability is scarce.

Three papers were classified as good or very good quality, while four were considered unsatisfactory. The most frequent methodological flaws were lack of controls and of representativeness of the investigated sample, because the studies had a small sample sizes and the subjects came from only two reference centers. The heterogeneity of variables prevented us from conducting a meta-analysis.

The results of these articles regarding pain prevalence and lower back pain were similar to those which were not included because of methodological criteria,4,6,15,16 showing that these characteristics are very consistent in HTLV-1. There is only one excluded paper where the result was not similar, but they included children, which was not in the scope of our review. This finding suggests that pain may be different between adults and children.16 Consequently, these results highlight that pain is consistently a problem in HTLV-1 infection, and that the lower back is the main affected region.

Regarding the definition of chronic pain, only one study defined the period considered to determine the chronicity of pain – more than three months.10 Another article did not clearly reported the used diagnostic criteria for chronic pain, but chronicity is implied by the long follow-up. Pain in HTLV-1 tends to be chronic, but remission has also been reported.12 As this phenomenon is poorly understood in HTLV-1 subjects, a more conservative approach in determining a cutoff point should be considered. The presence of continuous or frequent pain for more than six months is in agreement with the standards of the International Association for the Study of Pain,17 and should be used in future studies. Chronicity of pain was expected because neuropathological examinations evidenced chronic inflammatory lesions18 and HTLV-1 infection and HAM/TSP are chronic diseases without a definitive treatment.19

The general conception is that the pain in HAM/TSP is neuropathic, as it is commonly associated with other neurologic symptoms such as paraparesis and urinary disturbance, but a higher prevalence of this type of pain was found in HTLV-1 infected participants, irrespective of the presence of HAM/TSP.8

Despite this general concept, two studies found that non-neuropathic pain was more common than neuropathic pain in patients with HAM/TSP.10,11 One study used seven of 10 questions of the DN4, which lowers the cutoff point to define neuropathic pain from four to three. As the average DN4 score in this study was 1.72 (SD 1.50), we assume that a portion of the patients who were classified as non-neuropathic in fact had neuropathic pain. However, as the prevalence of non-neuropathic pain was very high (86.8%),11 this most likely would not change the assumption that non-neuropathic pain is frequent in HAM/TSP. The second study found a more balanced distribution between neuropathic (47.3%) and non-neuropathic pain (estimated to be 52.7%).10 However, it was not clear if they used seven or 10 questions of the DN4, and which cutoff point was considered. This may also have altered the results, but it probably would not dramatically modify the overall vision that both neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain are present in HAM/TSP.

The presence of non-neuropathic pain suggests a role of inflammation secondary to the infection in the pathophysiology of pain in HTLV-1. In general, the inflammatory activity is higher in HAM/TSP than in viral carriers without myelopathy.20 The release of local and systemic cytokines associated with inflammation mediated by cluster of differentiation antigen 4 (CD4) or CD8 T cells suggest that complex mechanisms may be involved in HTLV-1 pain. Inflammation in nervous and non-nervous structures is most likely the cause of the presence of both nociceptive and neuropathic pain, and these types may differ depending on the body region.21 Pain is not restricted to lower back and lower limbs and it was sometimes present in more than six body regions in the same subject,8 suggesting that HTLV-1 systemic involvement can lead to diffuse inflammation and pain.

Pain intensity was often moderate to severe in HTLV-1 and HAM/TSP participants, which suggests that it is misdiagnosed, misunderstood, and undertreated. Had pain been managed more adequately, severity would have probably been lower. The use of analgesics, NSAIDs and tricyclic antidepressants in one study was associated with some improvement in pain control,11 but there are no guidelines for the use of drugs for the control of symptoms in patients with HTLV-1. Clinical trials to investigate the impact of analgesic procedures in this population are strongly recommended. In addition to analgesics, these trials should also evaluate other drugs to control the disease.

Two trials not included in this review reported some improvement of pain. The first used Cyclosporin A in seven patients for 48 weeks,22 and another used transcranial direct current stimulation in 20 HTLV-1 infected participants.23 However, two other trials, one using Zidovudine plus Lamivudine in a six-month treatment regimen in 16 subjects,24 and the other using Prednisolone, Pegylated Interferon and Sodium Valproate in 13 participants for 25 weeks25 did not find significant differences between drugs and placebo regarding improvement of pain.

Pilates exercises and physical therapy (with proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) had clinical relevance in the control of the lower back pain in HTLV-1 infected patients and HAM/TSP patients.26,27 This suggests that pain in these patients may have, in part, a mechanical origin, which needs to be properly investigated. The major limitations of clinical trials regarding pain control are small sample sizes and short-term follow-up.

Two papers presented the impact of pain on quality of life, but only one was included in this review. However, both presented similar results showing that HAM/TSP patients with pain had lower SF-36 QoL scores compared to patients with the same disease but without pain.10,28 Although pain intensity is considered to be the main outcome in pain studies, the assessment of quality of life gives relevant information about the impact of the symptom in daily activities. Future studies should include QoL assessment along with pain outcomes, broadening the understanding of how patients deal with this harming symptom.

All studies included in this review came from only two countries, limiting the external validity of the conclusions. Further research needs to be done, especially with longitudinal design, with better methodological quality and trials including larger number of patients and longer follow-up periods.

Our findings summarize pain characteristics and prevalence among patients with HTLV-1, showing that it is common and ranges from moderate to severe intensity and affects quality of life in this population.

FundingThis study was funded by National Council for Scientific and Technologic Development (CNPq), and the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Databases searched: PUBMED, SciELO, MEDLINE, LILACS.

Limits: Human.

Filter: No filter.

- 1.

Pain AND HTLV

- 2.

Pain characteristics AND HTLV

- 3.

Pain prevalence AND HTLV

- 4.

((Pain) AND HTLV) NOT adult t cell leukemia lymphoma

- 5.

((Pain) AND (HTLV NOT adult t cell leukemia lymphoma)) NOT HIV

- 6.

((((Prevalence characteristics) OR pain) AND HTLV) NOT adult t cell leukemia lymphoma) NOT HIV

- 7.

((((Neuropathic) AND Nociceptive) OR pain) AND HTLV) NOT adult t cell leukemia lymphoma

- 1.

Pain Study Group includes: Tamires Cristina Martins de Vasconcelos, Pedro Larocca Magalhães, Kionna Oliveira Bernardes Santos, Katia Nunes Sá, Fernanda C. Queiros.