Clostridium difficile is a leading cause of diarrhea in hospitalized patients worldwide. While metronidazole and vancomycin are the most prescribed antibiotics for the treatment of this infection, teicoplanin, tigecycline and nitazoxanide are alternatives drugs. Knowledge on the antibiotic susceptibility profiles is a basic step to differentiate recurrence from treatment failure due to antimicrobial resistance. Because C. difficile antimicrobial susceptibility is largely unknown in Brazil, we aimed to determine the profile of C. difficile strains cultivated from stool samples of inpatients with diarrhea and a positive toxin A/B test using both agar dilution and disk diffusion methods. All 50 strains tested were sensitive to metronidazole according to CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints with an MIC90 value of 2μg/mL. Nitazoxanide and tigecycline were highly active in vitro against these strains with an MIC90 value of 0.125μg/mL for both antimicrobials. The MIC90 were 4μg/mL and 2μg/mL for vancomycin and teicoplanin, respectively. A resistance rate of 8% was observed for moxifloxacin. Disk diffusion can be used as an alternative to screen for moxifloxacin resistance, nitazoxanide, tigecycline and metronidazole susceptibility, but it cannot be used for testing glycopeptides. Our results suggest that C. difficile strains from São Paulo city, Brazil, are susceptible to metronidazole and have low MIC90 values for most of the current therapeutic options available in Brazil.

Clostridium difficile is a spore-forming Gram-positive bacillus. This microorganism produces two major toxins, enterotoxin A and cytotoxin B, that can cause diarrhea, pseudomembranous colitis, colon dilation, sepsis, and even death.1

The incidence and severity of C. difficile infections (CDI) is growing in many countries due in part to the dissemination of a hyper virulent strain known as North America Pulse type 1 (NAP1) or ribotype 027.2

Until the 1980s, there was little interest in researching new antibiotics for the treatment of CDI because most patients responded well to treatment with metronidazole or oral vancomycin. More recently, infection recurrence and the limitations of the available therapeutic options have become clearer.3 There are still doubts about the accuracy and correlation of different methods used to evaluate in vitro antibiotic sensitivity as well as the sensitivity of C. difficile strains to the recommended treatment regimens.

This study assessed the susceptibility profiles of a collection of C. difficile strains cultivated from stools of inpatients with diarrhea in six tertiary hospitals in São Paulo, Brazil. We also aimed to evaluate if disk diffusion method could be an alternative for susceptibility testing of the main drugs used in the treatment of CDIs. It was not a purpose of the study to evaluate the epidemiological data of the patients.

Materials and methodsClostridium difficile strainsConsecutive clinical strains of Clostridium difficile (n=50) were cultivated from stool samples of inpatients with diarrhea in six tertiary hospitals in São Paulo from March to December 2013 (one sample per patient). Stool samples were randomly selected for culture based on their positivity when tested with the ProScpect™ C. difficile Toxin A/B Microplate Assay (Thermo Scientific). Stool cultures for C. difficile were carried out as previously described, with modifications.4 In summary, approximately 0.5g of feces were mixed with 0.5mL 95% ethanol, vortexed and incubated at room temperature (20–25°C) for 1h. The suspension was vortxed again and two drops were plated on Brucella agar supplemented with 5% horse blood and 0.2% sodium taurocholate. Plates were incubated in a 2.5L anaerobic jar containg the Atmosphere Generation System AnaeroGen (Oxoid-Thermo Scientific) for 72h at 36°C. Identification to the species level was achieved by MALDI-ToF MS using the MALDI Biotyper LT System (Bruker).

The strains were stored in 10% skim milk at −70°C and subcultured on Brucella agar with 5% horse blood twice before utilization in susceptibility tests.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testingThe antimicrobials tested in this study were: metronidazole (Sigma-Aldrich), moxifloxacin (Sigma-Aldrich), nitazoxanide (Farmoquímica), teicoplanin (Sigma-Aldrich), tigecycline (Pfizer), and vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Disk diffusion was performed as described by Erikstrup et al.5 Cultured strains were suspended in thioglycollate broth to a density of 1.0 McFarland (≈3.0×108CFU/mL) with the aid of DensiCheck® (bioMérieux). The suspension was then seeded onto Brucella Blood Agar supplemented with 10% sterile defibrinated lysed horse blood, hemin (5μg/mL) and vitamin K (1μg/mL). To optimize the growth of C. difficile, plates were pre-reduced for 24h in an anaerobic atmosphere generated by the AnaeroGen system (Oxoid-Thermo Scientific) before use. For inoculum preparation, inoculation and incubation the 15-15-15 rule was followed.5

After 24h of incubation at 36°C in anaerobic atmosphere, generated with the aid of the AnaeroGen Atmosphere Generation Systems (Oxoid-Thermo Scientific), inhibition zone diameters were measured under reflected light considering 100% inhibition. Duplicate tests were performed for each strain on two separate days. The inhibition zone diameters were correlated with the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) obtained by agar dilution for each strain and drug combination.

For nitazoxanide and metronidazole 6-mm paper disks were prepared by adding 10μL of a 0.5mg/mL solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma), while for vancomycin and teicoplanin 6-mm paper disks with a potency of 5μg were prepared by adding 10μL of a 0.5mg/mL solution in reagent grade water. A 30μg teicoplanin disk (Oxoid-Thermo Scientific) was also tested. For tigecycline and moxifloxacin, we used commercially available disks (Oxoid-Thermo Scientific) containing 15 and 5μg, respectively. There are currently no interpretative criteria for disk diffusion when testing C. difficile.

For agar dilution bacterial strains were tested according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)6 and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)7 guidelines. Bacterial suspensions were prepared in thioglycollate broth to 0.5 McFarland turbidity (≈1.5×108CFU/mL) before 1μL of each suspension was transferred to the agar plates with the aid of a Steers replicator. Plates containing antibiotic were stamped starting from the lowest concentration. The MIC was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration inhibiting visible growth after 48h of incubation at 37°C in anaerobiosis. Tests were performed in duplicates.

The CLSI breakpoints for MICs were used for metronidazole and moxifloxacin,8 while EUCAST criteria were used for metronidazole and vancomycin.7 The interpretative criteria are summarized in Table 2. There are currently no interpretative criteria for tigecycline, teicoplanin, and nitazoxanide; consequently, only MIC50 and MIC90 values were calculated. For teicoplanin and nitazoxanide, the ECOFFinder spreadsheet9 was used to estimate epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFFs). C. difficile ATCC 700057 strain was used for quality control and tested simultaneously with each batch of antimicrobial susceptibility tests.

Statistical analysisFor metronidazole, moxifloxacin, and vancomycin categorical agreement between agar dilution and tentative interpretative criteria for disk diffusion was evaluated using CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints for agar dilution. The errors were classified as previously described.10

ResultsFrom March 1st to December 31st 2013 there were 1884 patients for which the detection of C. difficile toxins A and B by ELISA was ordered by the attending physicians. A total of 239 (12.7%) patients had a positive test. The mean age of patients with a positive test result was 61.3 years and most (61.1%) were female. A total of 50 fecal samples were ramdomly selected and cultured for isolation of C. difficile. The recovery rate was 100%. These isolates were confirmed to be C. difficile by mass spectrometry and were used for susceptibility tests.

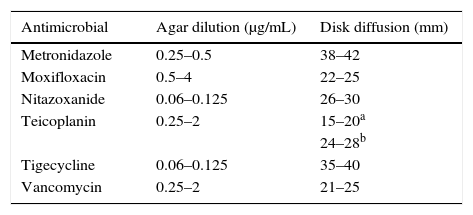

All the MIC results for the quality control strain C. difficile ATCC 700057 were inside the expected range recommended by the CLSI (Table 1). For teicoplanin, for which there is no CLSI or EUCAST expected range for this strain, the MIC range was 0.25–2μg/mL and the inhibition zone diameter ranged from 15 to 20mm and 24 to 28mm for the 5μg and 30μg disks, respectively (Table 1).

Minimal inhibitory concentrations and inhibition zone diameters obtained for C. difficile ATCC 700057 by the agar dilution and disk diffusion methods.

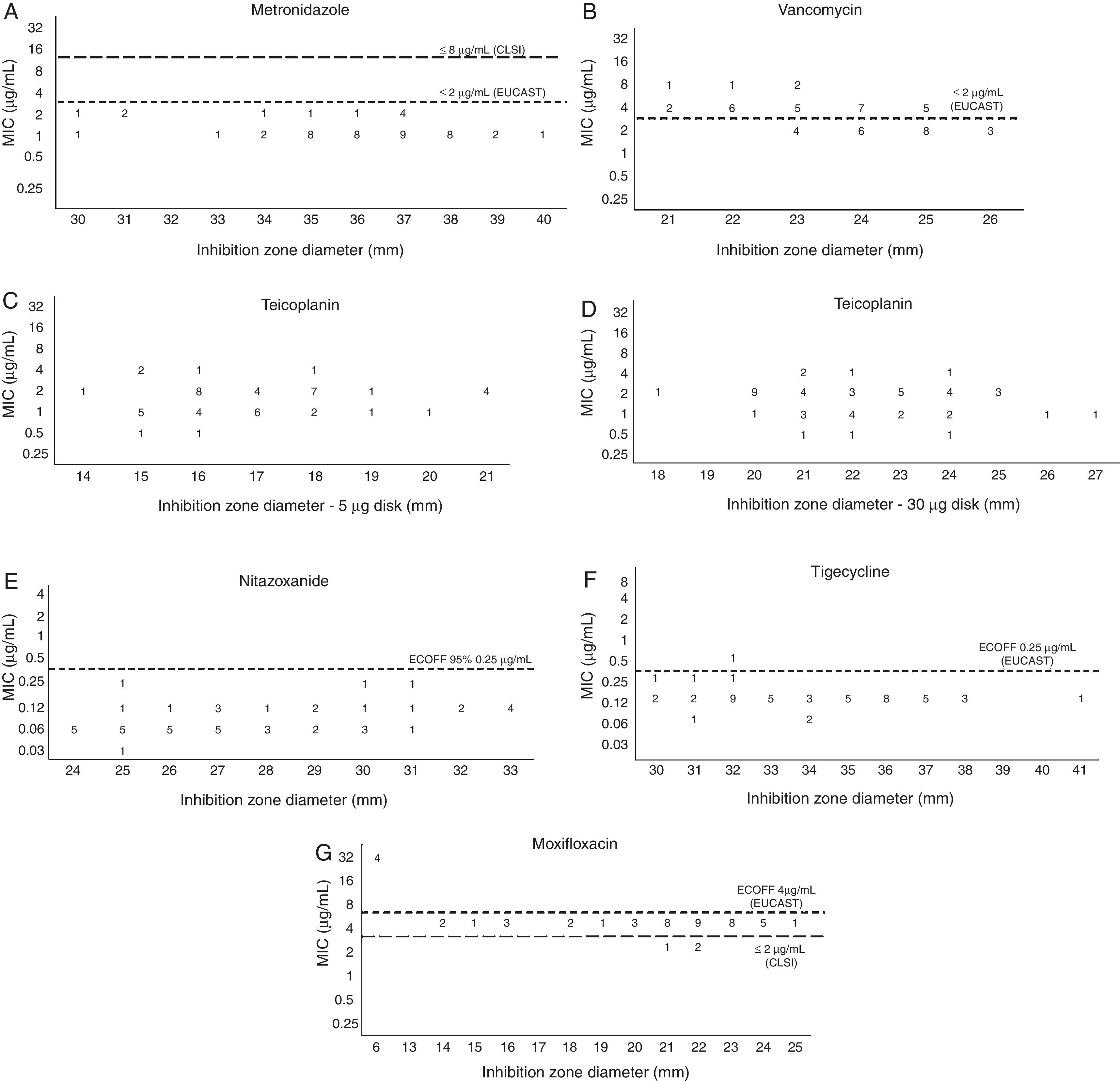

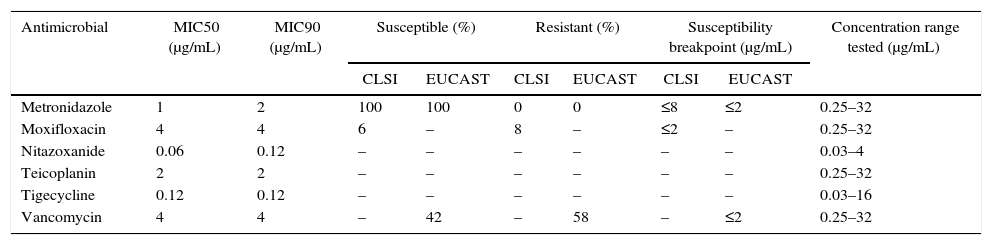

All tested strains were susceptible to metronidazole both by CLSI and EUCAST criteria. The MIC50 and MIC90 values are displayed in Table 2. Using 30mm as the susceptibility breakpoint for disk diffusion there would be 100% category agreement between agar dilution and disk diffusion methods (Fig. 1A).

Susceptibility profile of 50 Clostridium difficile isolates by agar dilution.

| Antimicrobial | MIC50 (μg/mL) | MIC90 (μg/mL) | Susceptible (%) | Resistant (%) | Susceptibility breakpoint (μg/mL) | Concentration range tested (μg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI | EUCAST | CLSI | EUCAST | CLSI | EUCAST | ||||

| Metronidazole | 1 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ≤8 | ≤2 | 0.25–32 |

| Moxifloxacin | 4 | 4 | 6 | – | 8 | – | ≤2 | – | 0.25–32 |

| Nitazoxanide | 0.06 | 0.12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.03–4 |

| Teicoplanin | 2 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.25–32 |

| Tigecycline | 0.12 | 0.12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.03–16 |

| Vancomycin | 4 | 4 | – | 42 | – | 58 | – | ≤2 | 0.25–32 |

There are currently no CLSI breakpoints for glycopeptides when testing C. difficile. Twenty-one strains (42%) had an MIC ≤2μg/mL for vancomycin and were classified as susceptible using the EUCAST breakpoint for C. difficile. MIC50 and MIC90 values are displayed in Table 2.

Using the 2μg/mL EUCAST susceptibility breakpoint for vancomycin none of the values obtained for inhibition zone diameter would result in a major error rate under 1.5% (Fig. 1B). The same was observed for teicoplanin (Fig. 1C and D), if we use the same EUCAST susceptibility breakpoint available for vancomycin, both with the he 5μg or the 30μg disks.

For nitazoxanide, the interpretation criteria for DD and MIC have not been defined by CLSI or EUCAST. The MIC50 and MIC90 values are displayed in Table 2. All strains with an inhibition zone diameter ≥24mm had an MIC value ≤0.25μg/mL, the calculated ECOFF value (Fig. 1E).

There are currently no tigecycline susceptibility breakpoints according to CLSI or EUCAST. The MIC50 and MIC90 are displayed in Table 2. The calculated ECOFF was 0.25μg/mL. All isolates, except one, had an inhibition zone diameter ≥30mm and an MIC higher than 0.25μg/mL (Fig. 1F).

For moxifloxacin, both the MIC50 and MIC90 were 4μg/mL (Table 2). Four (8%) strains had high MIC values of 32μg/mL (Fig. 1G). Applying the CLSI susceptibility breakpoint of 2μg/mL for moxifloxacin, only 6% of the strains would be considered susceptible. Using this MIC breakpoint, none of the values obtained for inhibition zone diameter would result in a very major error rate under 1.5%.

DiscussionWe evaluated the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of a collection of 50 C. difficile strains using both agar dilution and disk diffusion.

All strains were susceptible to metronidazole, and the highest MIC value was 2μg/mL, two dilutions bellow the susceptibility breakpoint of 8μg/mL recommended by the CLSI. These findings agree with a recent publication that evaluated a large collection of strains from Europe and found the same MIC90 values.11

Although we did not detect resistant strains, metronidazole resistance in C. difficile has been reported very rarely. Freeman et al.11 found only one isolate with an MIC value ≥8μg/mL among 916 tested by agar dilution. Concerning the metronidazole disk diffusion method5,5,12 we found that an inhibition zone diameter ≥30mm for a metronidazole disk containing 5μg can be indicative of susceptibility, while Erikstrup and colleagues5 recommend using 23mm as the breakpoint. This difference between breakpoints is most probably due to the number of strains tested in this work, but all strains classified as susceptible by the 30mm breakpoint would also be classified as susceptible with the 23mm breakpoint.

Oral metronidazole has been recommended as the treatment of choice for mild disease while oral vancomycin is usually recommended for the treatment of severe infections and recurrences.13 In this study the MIC90 for vancomycin was 4μg/mL, which is one dilution above the value found by Freeman et al.11 Our results may not be comparable to theirs, because they used the Wilkins-Chalgren agar and we used Brucella agar. Baines et al.14 demonstrated that MIC values obtained using Brucella agar for agar dilution were lower than those obtained when using Etest strips. Erikstrup and colleagues5 used the Etest and not the gold standard agar dilution. Consequently, this may explain why we did not find good correlation between disk diffusion and agar dilution methods. Our results contrast to those from Erikstrup and colleagues,5 since in this work no inhibition zone size would result in a very major error rate below 1.5%. Our results agree well with previous findings that supported the witdrawal of the interpretative criteria for vancomycin disk diffusion, when testing Staphylococcus, from CLSI documents.15 There are no CLSI interpretative criteria for vancomycin when testing C. difficile, while EUCAST recommends a susceptibility breakpoint of 2μg/mL. Based on this breakpoint, Freeman et al.11 reported a low (0.87%) resistance rate when testing a large collection of strains. Although the results from this study are different from those of Freeman et al.,11 our findings are supported by the fact that the mean vancomycin MICs obtained for the quality control strain C. difficile ATCC 700057 was 2μg/mL, which is one dilution below the upper limit.8

Teicoplanin and nitazoxanide are alternative treatments for CDI3,16 but there are currently no susceptibility breakpoints defined by EUCAST or CLSI. The MIC90 obtained for teicoplanin in this study is two dilutions above that obtained by Barbut et al.17 This difference is probably due to the fact that we used Brucella agar and they used Wilkins-Chalgren agar. Baines et al.14 demonstrated that agar dilution with Wilkins-Chalgren agar generates results one dilution lower than those generated by Brucella agar.

In this study the MIC90 for nitazoxanide was 0.125μg/mL. This finding agrees with a previous study from Freeman et al.18 that tested strains from ribotypes 001, 027 and 106 with reduced susceptibility to metronidazole. To date there are no reports on the nitazoxanide disk diffusion method for C. difficile. Although in this work we did not find nitazoxanide isolates with high MICs, our results indicate that 24mm could be used as a screening for isolates with MICs ≤0.125μg/mL.

There are some reports in the literature that describe tigecycline as an alternative therapeutic option for patients with refractory CDI.19 In this study we obtained an MIC90 of 0.125μg/mL for this antimicrobial. This value is the same as obtained by Hecht et al.20 There are currently no EUCAST or CLSI susceptibility breakpoints for tigecycline when testing C. difficile, but EUCAST recommends an ECOFF of 0.25μg/mL. Using this value as a susceptibility breakpoint, 98% of the strains would be considered susceptible. There are currently no reports on disk diffusion for tigecycline when testing C. difficile. Although in this work we did not find isolates with a high tigecycline MICs, our results indicate that 30mm could be used as a screening for isolates with MICs ≤0.5μg/mL.

Resistance to fluoroquinolones has been suggested as a screening for the presence of the hyper virulent strain NAP1/BI/027.21,22 CLSI recommends 2μg/mL as the susceptibility breakpoint value, while strains with an MIC of 4μg/mL should be classified as intermediate. EUCAST has no susceptibility breakpoint for moxifloxacin when testing C. difficile, but recommends an ECOFF value of 4μg/mL.

In this study the MIC90 was 4μg/mL and four strains had an MIC ≥32μg/mL. Using CLSI breakpoints 6% of the strains would be classified as susceptible, 86% intermediate, and 8% resistant. This resistance rate is much lower than that found in Europe (39.9%) by Freeman and colleagues.11 To date there is no report on the presence of the 027 ribotype emerging in Brazil and possibly this low resistance rate indicates the predominance of ribotypes other than 027, but ribotyping was not performed in this study. If we had used 13mm as the resistance breakpoint, then the four resistant strains would have been detected. We found a superposition of intermediate and susceptible categories by disk diffusion. Consequently, this method cannot be used to preview susceptibility but can be used to screen for moxifloxacin resistance.

ConclusionsAll strains tested in this study were susceptible to metronidazole according to EUCAST and CLSI breakpoints. Nitazoxanide and tigecycline were higly active, both with an MIC90 of 0.125μg/mL. The MIC90 were 4μg/mL and 2μg/mL for vancomycin and teicoplanin, respectively.

The disk diffusion method can be used to screen for metronidazole, tigecycline and nitazoxanide susceptibility, and moxifloxacin resistance but cannot be used for testing vancomycin and teicoplanin.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.