A population-based survey conducted in Brazilian capital cities found that only 16% of the population had ever been tested for hepatitis C. These data suggest that much of the Brazilian population with HCV infection remains undiagnosed. The distribution of age ranges at diagnosis and its association with the degree of hepatitis C are still unknown in Brazilian patients.

Material and methodsPatients with HCV infection, diagnosed by HCV RNA (Amplicor-HCV, Roche), were included in the study. Patients with HBV or HIV coinfection, autoimmune diseases, or alcohol intake>20g/day were excluded. HCV genotyping was performed by sequence analysis, and viral load by quantitative RT-PCR (Amplicor, Roche). The METAVIR classification was used to assess structural liver injury. The Chi-square (χ2) test and student's t-test were used for between-group comparisons. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient were used for analysing the correlation between parameters.

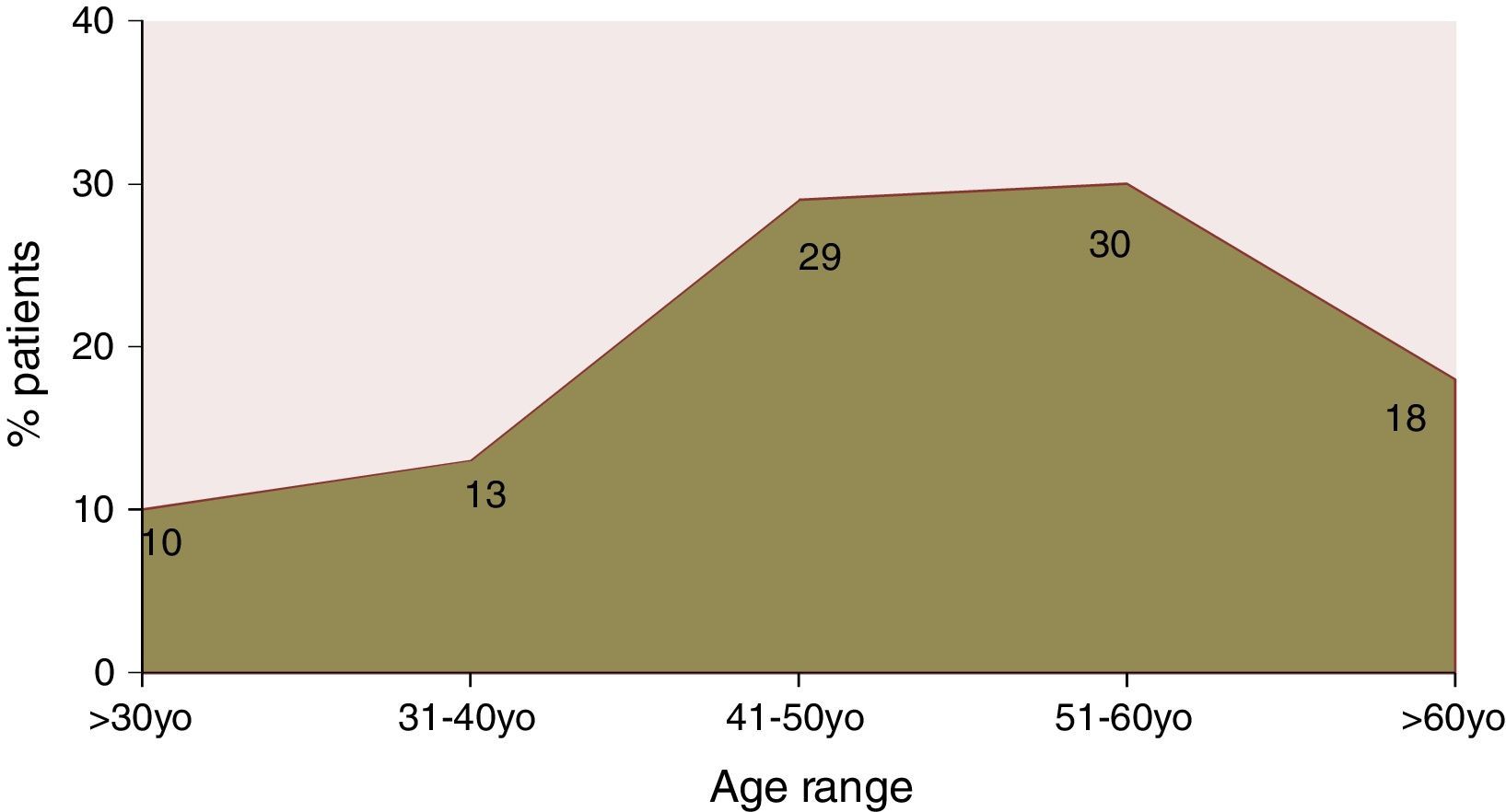

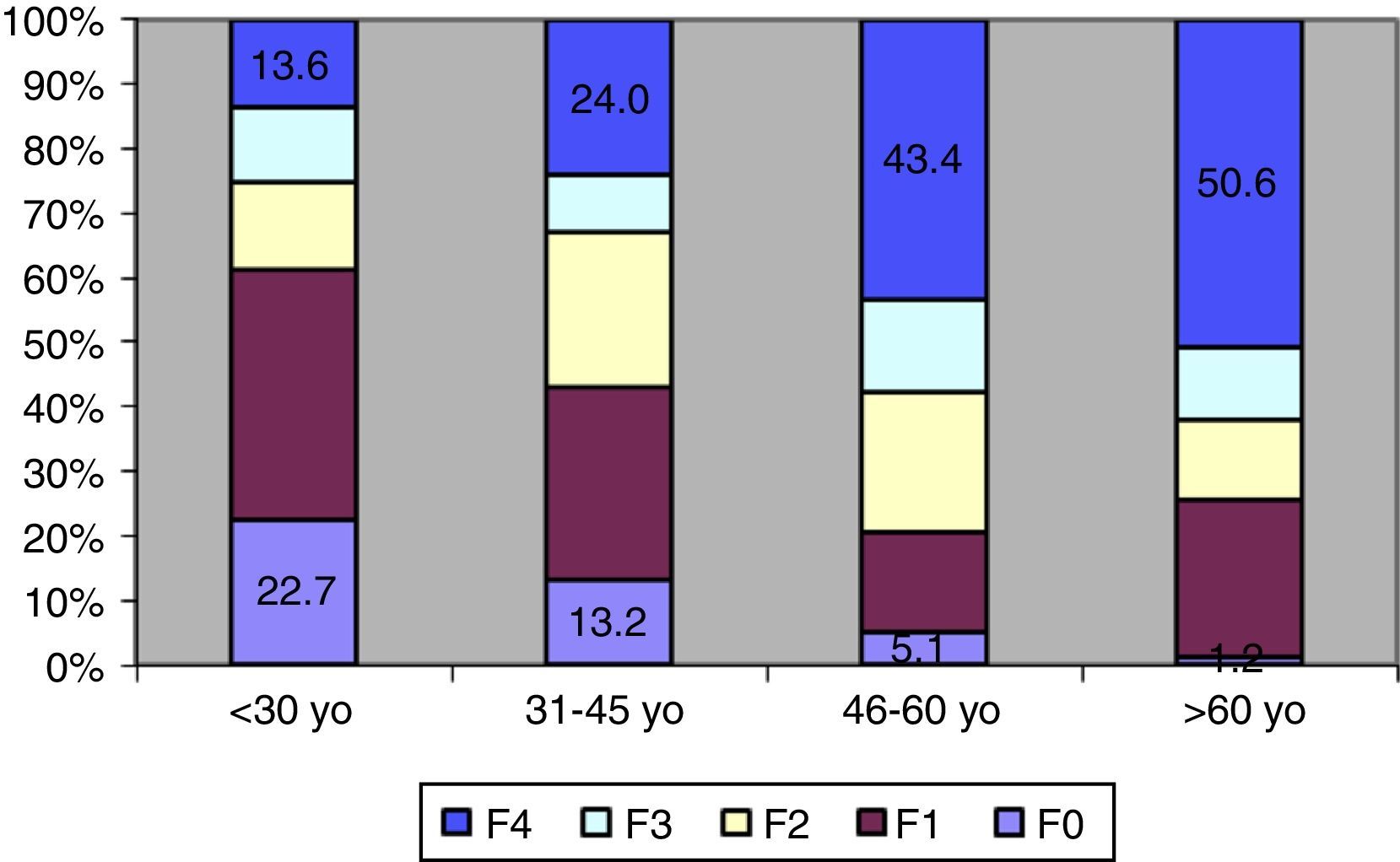

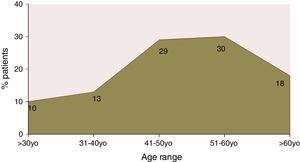

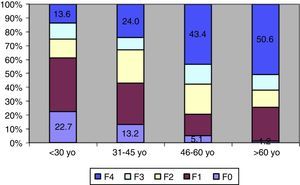

ResultsA total of 525 charts were reviewed. Of the patients included, 49.5% were male, only 10% of the patients were aged less than 30 years; peak prevalence of HCV infection occurred in the 51-to-60 years age range. Genotype 1 accounted for 65.4% of the cases. Information on HCV subtype was obtained in 227 patients; 105 had subtype 1a and 122 had 1b. According to the degree of structural liver injury, 8.3% had F0, 23.4% F1, 19.8% F2, 11.9% F3, and 36.5% F4. Age at diagnosis of hepatitis correlated significantly with fibrosis (rs=0.307, p<0.001). The degree of fibrosis increased with advancing age. Only age at diagnosis and fasting blood glucose were independently associated with disease stage. Those patients with subtype 1a had higher prevalence of F2–F4 than those with subtype 1b.

ConclusionIn Brazil, diagnosis of hepatitis C is more commonly established in older patients (age 45–60 years) with more advanced disease. Reassessment of strategies for hepatitis C diagnosis in the country is required.

According to official estimates of the prevalence of hepatitis C in Brazil and demographic data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE),1,2 approximately 2.5 million people in the country would have been positive for anti-hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) antibodies. A population-based survey conducted in major state capitals found that only 16% of the population had ever been tested for HCV.3 Just over 60,000 patients with hepatitis C have received antiviral treatment in the country over the last 6 years.4 These data show that a large portion of the Brazilian population infected with HCV remains undiagnosed. The high prevalence of advanced hepatitis C in the country appears to reflect the lack of an aggressive policy for diagnosing this serious condition, which is compounded by its oligosymptomatic course. Hepatitis C is the second leading cause of cirrhosis in Brazil and the leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma, and, consequently, the most common cause of liver transplantation in the country.5–7 However, no consistent data are available on the association between age range at diagnosis and disease progression. Therefore, the present study sought to assess the demographic profile of patients with confirmed HCV infection presenting for their first visit at a tertiary referral center, and ascertain whether correlations exist between this variable and clinical and histological severity of the illness.

Material and methodsWe reviewed the charts of all adults (age>15 years) seen consecutively between January 2009 and June 2013 at the outpatient Gastroenterology Clinic of Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), a tertiary referral service for patients with HCV-related liver disease. The inclusion criterion was a confirmed HCV infection. After diagnosis of HCV exposure, usually by detection of anti-HCV antibodies by second-generation and, later in the study period, third-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Abbott IMX, Abbott Laboratories, USA), diagnosis was confirmed by detection of HCV RNA in peripheral blood through the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Amplicor-HCV, Roche Diagnostics). HCV genotyping was later carried out by sequence analysis of the 5′ noncoding region, and viral load was measured by quantitative RT-PCR (Amplicor, Roche).

For analysis of the association between age at diagnosis and degree of liver injury, gender distribution, and distribution of viral genotypes, we excluded patients with hepatitis B virus or HIV coinfection, autoimmune diseases, or alcohol intake>20g/day (regardless of gender). All patients had undergone percutaneous liver biopsy, except those with clinical manifestations or ultrasound and/or endoscopy findings consistent with cirrhosis. The resulting biopsy specimens were embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E), reticulin, and Masson's trichrome for histological examination. On histopathological analysis, structural liver injury was assessed and graded in accordance with the histological METAVIR classification.8

Statistical analysis: Results were expressed as means and standard deviations. The Chi-square (χ2) test or student's t-test was used for between-group comparisons as appropriate. Spearman's rank was used to test for correlation between parameters. The significance level was set at 5% (p<0.05).

ResultsInitial assessment included the charts of 525 patients with HCV infection, of whom 49.5% were male and 50.5% were female. Only 10% of these patients were aged<30 years at diagnosis; peak prevalence occurred between the ages of 51 and 60 years (Fig. 1).

In 61 patients with confirmed viral infection, liver injury could not be staged due to their refusal to undergo biopsy, loss to follow-up, or the presence of exclusion criteria not identified at the time of enrollment. The remaining 464 patients had a gender distribution similar to that of the initial sample and a mean age of 48.9±12.4 years (range, 15–78 years). Regarding genotype, 65.4% had genotype 1 HCV, 29% had genotype 3, 7% had genotype 2, and 4% had other genotypes. Furthermore, HCV subtype was determined in 227 patients with genotype 1: 105 had subtype 1a and 122 had subtype 1b. Regarding the distribution of degrees of structural liver injury, 8.3% of patients had no fibrosis (F0), 23.4% were graded as F1, 19.8% as F2, 11.9% as F3, and 36.5% as cirrhotic (F4).

Age at diagnosis of hepatitis correlated significantly with the degree of structural liver injury (rs=0.307, p<0.001). As shown in Fig. 2, degree of fibrosis increased with advancing age. The percentage of patients with cirrhosis also increased progressively with increasing age range at diagnosis; conversely, the percentage of patients with mild or no fibrosis decreased progressively with advancing age. The presence of advanced fibrosis did not correlate with gender, body mass index, genotype, viral load, or epidemiology of infection.

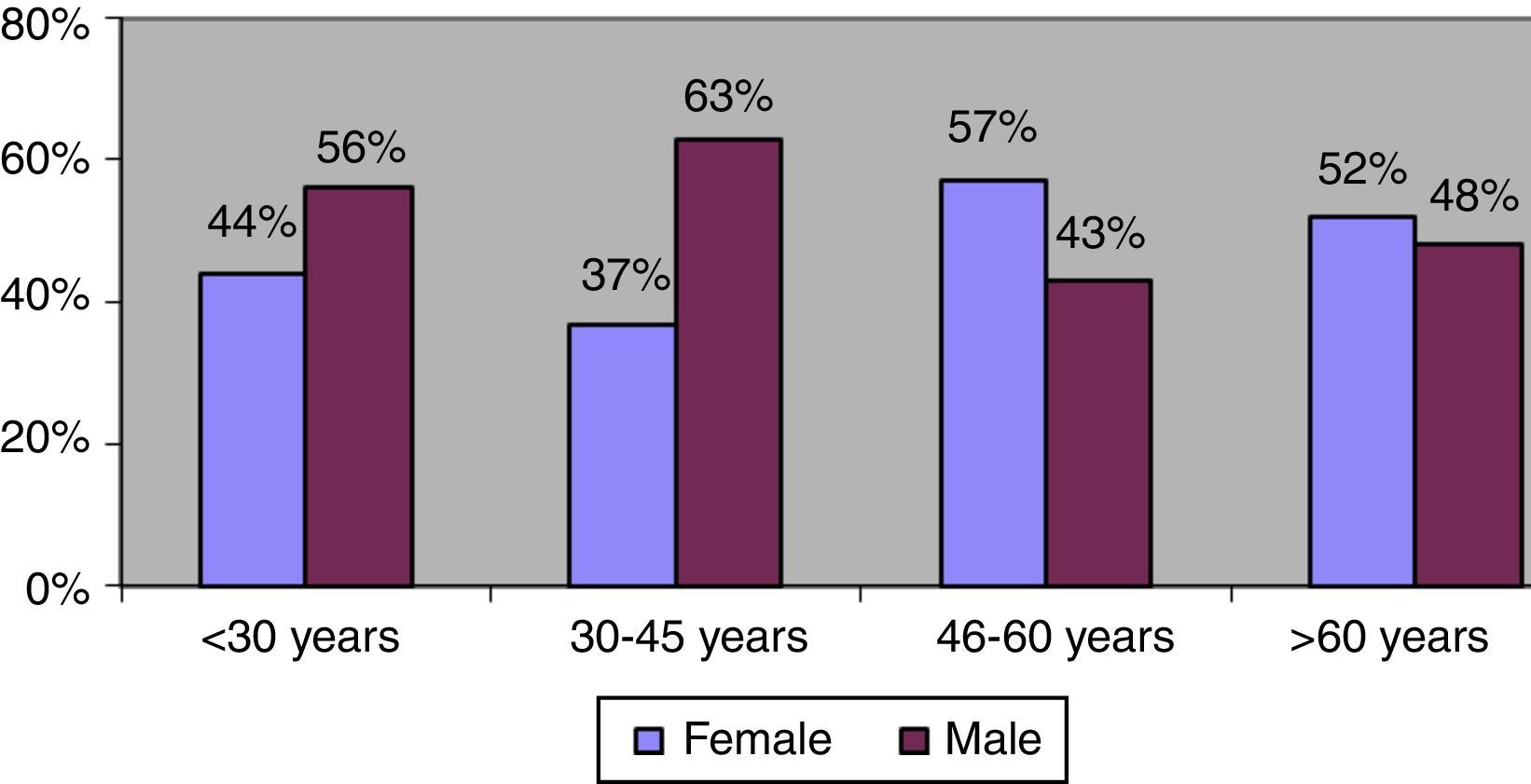

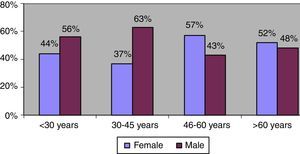

The gender distribution was reversed among patients diagnosed after age 45 years. Among patients younger than this cutoff, men accounted for 60% of all diagnosed cases, whereas after this age, women were the majority, accounting for 55% of cases on average (Fig. 3). However, there were no significant gender differences in the degree of fibrosis (χ2=2.221, p=0.695) or the distribution of viral genotypes (χ2=1.185, p=0.757) in this age range.

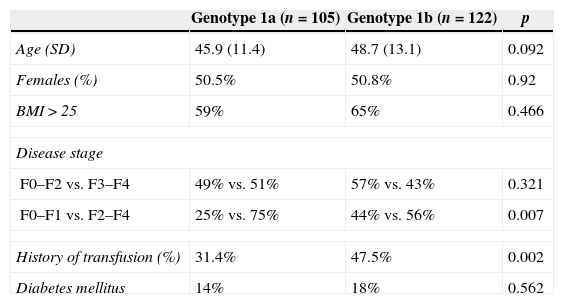

There were no significant differences in gender, age, body mass index, or the presence of diabetes mellitus among different genotype 1 HCV subtypes. However, when patients were stratified by disease stage, despite no differences in the presence of advanced fibrosis (F3, F4), patients with subtype 1a had a statistically higher prevalence of substantial fibrosis (F2–F4) than patients with subtype 1b. A history of blood transfusion was more prevalent among patients with subtype 1b (Table 1).

Clinical, demographic, and histological features of patients with hepatitis C genotype 1, stratified by HCV subtype.

| Genotype 1a (n=105) | Genotype 1b (n=122) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 45.9 (11.4) | 48.7 (13.1) | 0.092 |

| Females (%) | 50.5% | 50.8% | 0.92 |

| BMI>25 | 59% | 65% | 0.466 |

| Disease stage | |||

| F0–F2 vs. F3–F4 | 49% vs. 51% | 57% vs. 43% | 0.321 |

| F0–F1 vs. F2–F4 | 25% vs. 75% | 44% vs. 56% | 0.007 |

| History of transfusion (%) | 31.4% | 47.5% | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14% | 18% | 0.562 |

Although restricted to the adult population, these data show that diagnosis of hepatitis C in Brazil increases in prevalence from the fourth decade of life and that nearly half of all patients in whom the condition is detected are diagnosed between the ages of 46 and 60 years, with peak prevalence at age 50–60 years. These data essentially reproduce those reported by Foccacia et al., 9 who conducted a seroepidemiologic population-based survey of anti-HCV antibody positivity in the city of São Paulo and found that the most significant prevalence was found after age 30 years, with peak prevalence at 50–60 years. These findings were also consistent with the distribution of cases reported to the Brazilian Ministry of Health Notifiable Diseases Information System (Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação, Sinan).10

Another remarkable finding of this study was the impact of age at diagnosis on the degree of liver injury, with a growing prevalence of advanced fibrosis and a progressive reduction in the number of mild cases with advancing age. On analysis of factors associated with disease progression, only age and the presence of diabetes mellitus correlated with more advanced disease in our sample. The importance of age in the natural history of chronic hepatitis C has been demonstrated in a variety of studies conducted in Brazil and elsewhere. Patients infected at an older age or those with a longer disease course present with more advanced stages.11–14 Several investigations have demonstrated rapid disease progression among patients infected at older ages, particularly in studies of patients enrolled with early-stage fibrosis (F0, F1), where progression to advanced fibrosis was more common among patients older than 40–50 years.15,16

The most significant conclusion one can draw from the data presented herein is that, in addition to diagnosing only a minute portion of those persons who are actually infected with HCV in Brazil, the majority of these patients are being diagnosed at advanced stages of hepatitis C. The lack of early diagnosis of hepatitis C (i.e., during the asymptomatic stage) hinders its curative treatment and has a major impact on health expenditures. Indeed, the costs of treating the complications of cirrhosis and performing liver transplantation far exceed those of therapy aimed at eradicating the virus. Several studies have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of broader programs for HCV detection and diagnosis based on patient age rather than testing of high-risk groups alone.17,18 These studies led the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to recognize a need for expansion of the established HCV risk groups to include the so-called “baby boomer” generation, i.e., persons born in the years 1945–1965.19

On the other hand, the finding that patients are being diagnosed at more advanced stages of the disease is a cause for concern, as these patients are known to respond relatively poorly to antiviral therapy, whether with interferon alfa/pegylated interferon and ribavirin or with protease inhibitor-based triple therapy; furthermore, these patients experience more adverse effects during treatment.20–23

In the present study, we were unable to identify any changes in the mode of disease transmission over time. Blood transfusion was the leading known potential source of disease transmission, followed by intravenous drug use. Blood transfusion had occurred, on average, 32.4±9.7 years before diagnosis (median, 33 years). This probably explains the age difference in gender distribution. There was an increase in the prevalence of women being diagnosed with HCV as age advanced, but gender was not significantly associated with the degree of fibrosis. The best explanation for this finding appears to be slower progression of liver disease in women,14,24 which is corroborated by the prolonged clinical course seen in these patients. Indeed, most of these patients still had blood transfusion as the most important factor for disease transmission.

Another interesting finding in this study was provided by HCV subtype analysis. Some investigations have suggested that subtype 1b would be associated with more marked disease progression and a greater trend toward development of hepatocellular carcinoma than subtype 1a.25–27 Other authors, however, maintain that these negative findings are only associated with the more advanced age of patients with subtype 1b, who are believed to be phylogenetically older than those with subtype 1a.25–27 Although patients with subtype 1b in our case series had a greater mean age and were more likely to have contracted HCV through blood transfusion (which reinforces the notion of phylogenetic precedence), we found no significant differences in the degree of fibrosis when patients were stratified using advanced fibrosis (grade F3/F4) as a cutoff. Conversely, when grade F2 (substantial fibrosis) was used as the cutoff for patient stratification, we found a greater frequency of substantial fibrosis among patients with subtype 1a than among those with subtype 1b. There were no significant differences in gender, age, body mass index or the presence of diabetes among the subtypes, which suggests that higher-grade fibrosis was exclusively attributable to HCV subtype. As this was a retrospective study and subtype analysis was limited to patients with genotype 1 HCV, we cannot confirm these findings. However, a more in-depth investigation of the relationship between genotype 1 subtypes and progression of hepatitis C in Brazilian patients is certainly warranted.

This study clearly shows that methods for diagnosing hepatitis C infection must improve in Brazil. If we continue to diagnose patients after the age of 50 years, we will be selecting for cases that are more likely to develop complications, less likely to respond to antiviral therapy, and more likely to develop cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and require liver transplantation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.