Leprosy can be considered a dissimulated disease, mainly when presented as atypical cases leading to mistaken diagnosis at the emergency setting. Herein we report six patients referred to the emergence room with hypotheses of acute myocardial infarction and arterial and venous thrombosis, although with chronic neurological symptoms; the seventh patient was referred with a wrong suspicion of infected skin ulcer. Positive findings included hypo-anesthetic skin lesions and thickened nerves; 100% were negative for IgM anti-phenolic glycolipid-I, while 71.4%, 100% and 42.8% were positive for IgA, IgM and IgG Mce1A. RLEP-PCR was positive in all patients. Ultrasound of peripheral nerves showed asymmetric and focal multiple mononeuropathy for all patients. Unfortunately, in many patients leprosy is often misdiagnosed as other medical conditions for long periods thus delaying initiation of specific treatment. This paper is intended to increase physicians’ awareness to recognize leprosy cases presented as both classical and unusual forms, including in emergency department.

Leprosy diagnosis is still a challenge worldwide mainly because of the multifaceted clinical presentation. Leprosy expertise is declining among physicians, even in endemic areas, and focusing almost exclusively on cutaneous signs results in a non-timely diagnosis.1 In contrast, the neurological symptoms that worsen over time (tingling, electric-shock pain, foot-drop, loss of sensation, muscle cramp) can emulate many clinical conditions,1 therefore presenting as an atypical case at the emergency room (ER). Usually in leprosy, only acute reactions are treated as emergency;2 however, among many patients cared at the emergency department, certainly there are patients with undiagnosed leprosy.

Diagnosis of leprosy, essentially clinical, is based upon detection of at least one of the following signs/symptoms: a) lesion(s) and/or area(s) of the skin with changes in thermal and/or pain and/or tactile sensitivity; b) thickening of peripheral nerve(s), associated with sensory and/or motor and/or autonomic changes; and/or c) presence of M. leprae, confirmed by smear microscopy or skin biopsy,3 that can be confirmed by RLEP-PCR.4,5

As a complement to the clinical evaluation, there are quantitative assessments of anti-glycolipid-I (anti-PGL-I) and IgA, IgM and IgG antibodies against the anti-mammalian cell entry 1A (anti-Mce1A) protein by indirect ELISA.4,6

Considering that neural involvement is present in all clinical forms of leprosy, as damage to the nerve trunks and/or cutaneous nerve endings,5,7 the evaluation of these nerves by ultrasound is helpful due to the possibility of examining a larger territory of the nerve that may be inaccessible to clinical examination, as well as better locating and defining the thickening point and/or peripheral nerve alteration.8

The objective of this report is to draw attention to mistaken referrals of atypical clinical leprosy cases with chronic neurological symptoms to the ER, underscoring the need to improve the teaching of leprosy for all health professionals, mainly in medical schools.

Case seriesThis is a cross-sectional study carried out at a tertiary referral hospital in Ribeirão Preto, inner São Paulo, Brazil. The emergency department (ED) where this study was carried out, there are approximately 650 visits monthly, all of them referred from secondary health care units following medical evaluation. The sampling frame of the study includes patients who accessed care at the ED from April 2020 through April 2021.

Herein, we report a case series of leprosy patients diagnosed at the ER, aged 34 to 75 years; clinical features and complementary exams are detailed in Table 1 to 4. Of the referred patients, three were suspected of having acute coronary syndrome, as they complained of tingling in the left upper limb without chest pain, electrocardiograms with sinus rhythm without ischemic cardiac changes and normal-range cardiac markers. Two other patients were suspected of acute arterial occlusion, and another patient of deep vein thrombosis, as they all complained of unilateral leg pain and two of them had feet-drop. Venous and arterial ultrasounds were normal. The sixth patient was referred with a suspicion of an infected skin ulcer.

Patient demographics, presenting symptoms, clinical and peripheral nerves ultrasound characterization.

Legend: AAO acute arterial occlusion; ACS acute coronary symdrom; CSA cross-sectional area; DVT deep vein thrombosis; LUL left upper limb.

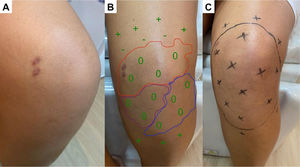

Positive dermatoneurological findings on examination included hypo-anesthetic skin lesions (Figs. 1–3), thickened nerves and altered hands (42.8%) and feet (100%) tactile sensitivity. All cases were multibacillary and had some grade disability (GD), with 42.9% of G2D.

(A) Hypochromatic, hypo-anesthetic macule on the left upper limb; (B) Areas with loss of tactile sensitivity [green dashed area = 0.07 gram-force (normal threshold of tactile sensitivity); blue dashed area = 0.2 g-f; purple dashed area = 2.0 g-f; red dashed area = 4.0 g-f]; (C-D) improvement of tactile sensitivity after five months of multibacillary multidrug therapy.

(A) Hypochromatic, hypo-anesthetic macule on the left knee; (B) Areas with loss of tactile sensitivity [anesthetic (0), hypoesthetic (-) and normoesthesic (+) points to green monofilament (0.07 g-f, normal threshold of tactile sensitivity); blue dashed area = 0.2 g-f; purple dashed area = 2.0 g-f; red dashed area = 4.0 g-f); (C) improvement of tactile sensitivity after six months of multibacillary multidrug therapy.

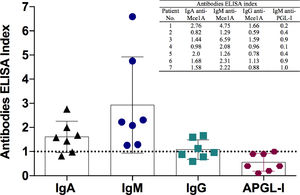

Considering serological results, 100% (7/7) were negative for IgM anti-PGL-I, 71.4% (5/7), 100% (7/7) and 42.8% (3/7) were positive for IgA, IgM and IgG anti Mce1A protein of Mycobacterium antibodies, respectively (Fig. 4). Mycobacterium leprae DNA RLEP-PCR was positive in 100% (7/7) patients. Ultrasound of peripheral nerves showed asymmetric and focal multiple mononeuropathy in all patients, four with intraneural Doppler signal (Fig. 5).

Leprosy serology: comparison of antibodies levels by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) against IgM anti-PGL-I (APGL-I) and IgA, IgM and IgG anti-Mce1A antigens of M. leprae. The respective index was calculated by dividing the optical density of each sample by the cut-off, and indexes above 1.0 were considered positive.

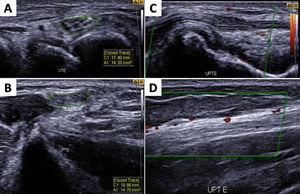

Ultrasonography showing asymmetric neuropathy at the left ulnar nerve with thickened transverse sectional areas in the cubital tunnel (A-UTE) and in the distal region of the arm (B-UPTE) with hyperechoic perineurs and evident fascicular distention (C), in addition to blood flow in the epineural and intraneural region (D) as a sign of active neuritis.

All patients started multidrug therapy (MDT/WHO). Two of them also used prednisone 1 mg/kg/day with slow reduction of neural inflammation. All patients showed significant improvement in dermatological signs and neurological symptoms under specific antimicrobial treatment.

For leprosy surveillance, 15 intra-domiciliary contacts from four leprosy patients were also evaluated, and three (20%) new leprosy patients were diagnosed, all from the same family.

DiscussionThe decline in leprosy prevalence and the commitment to leprosy elimination as a public health problem in many countries have been accompanied by a decline in disease expertise.9 Leprosy can mimic many common dermatological and neurological conditions,4,5 leading to delays in diagnosis. However, even in the presence of anesthetic lesions with thickened nerves, hallmarks signs, many physicians seem to lack the skills to diagnose leprosy, even the classic forms. In routine, almost exclusively neuritis is considered an emergency in leprosy, an exclusive sign to justify emergency care because of acute neural damage and sensory and/or motor disability. Surprisingly, all our patients had a history of chronic neural pain, longer than three months, but only four of them showed neuritis on ultrasound (positive intraneural Doppler signal). Additionally, all patients had altered feet tactile sensitivity test, also defining the pattern of asymmetrical and focal multiple mononeuropathy in leprosy diagnosis, and also for the clinical-therapeutic follow-up.

Serological techniques and PCR are used as complementary tests, but unfortunately they are only restricted to referral and research centers. PGL-I-serological positivity may indicate continuous exposure to the bacillus in the community, but negative results do not exclude the diagnosis of leprosy. In addition to clinical findings, we also used serological tests with a new biomarker (Anti-Mce1A) that indicates active or previous disease, and/or for screening of household contacts. The anti-Mce1A antibodies (IgA, IgM and IgG) showed significantly better diagnostic performance than anti-PGL-I, as already described, with sensitivity and specificity ranging from 74.2-100% and 89.1-100%, respectively,6 while anti-PGL-I showed lower seropositivity range of 23-78% among leprosy patients.6

As published before by Frade et al.,8 we analyzed the cross-sectional areas (CSA) in median nerves (carpal tunnel and distal forearm), ulnar nerves (cubital tunnel and distal arm), common fibular nerves (head of fibula and distal thigh) and tibial nerves (posterior to the ankles). Nerve asymmetry was calculated by the difference between the biggest and the smallest CSA in the same nerve point. Nerve focallity was calculated by the difference between two points (proximal and distal CSA) in the same nerve. Qualitative morphological alterations were defined by loss of fascicular nerve pattern, heterogeneous fascicular distention, signs of perineural fibrosis. The intra-nerve Doppler positive sign is indicative of active neuritis.

Ultrasonography is a technique that allows good quantitative and qualitative representation of peripheral, superficial and deep nerves by measuring cross sectional areas and provides information about echotextural changes and fascicular patterns in neuropathies, which allow the detection of asymmetry and focallity of peripheral nerve thickening.8,10 Ultrasound evaluation was in line with the multibacillary classification of the patients, since 100% showed nerve thickening, even in those presenting only hypochromatic macular lesions, as clinical signs.

In the daily routine of health services, the unavailability of complementary molecular biology and serologic tests to detect the different clinical forms of leprosy, the reaction states and the identification of subclinical infection are challenges to control the magnitude of the disease, leading to misdiagnosis at the ER.

Attention to the possibility of leprosy diagnosis at emergency services should be paid not only in countries considered endemic, but in all countries where the medical expertise on leprosy is far from ideal. This case series exemplifies the need to strengthen the teaching of leprosy health professionals both in graduate courses and residency programs of the various specialties, as well as the importance to continuously promote leprosy education among health workers. All clinicians must be alert to neurological symptoms, mainly the neural pain, besides dermatological signs of leprosy, allowing for an early diagnosis thus avoiding many cases of irreversible nerve damage and interrupt the chain of disease transmission

Financial supportThis work was supported by the Center of National Reference in Sanitary Dermatology focusing on Leprosy of Ribeirão Preto Clinical Hospital, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil; the Brazilian Health Ministry (MS/FAEPAFMRP-USP: 749145/ 2010 and 767202/2011); Fiocruz Ribeirão Preto - TED 163/2019 - Processo: N° 25380.102201/2019-62/ Projeto Fiotec: PRES-009-FIO-20. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributionsAll authors meet the criteria for authorship, including acceptance of responsibility for its scientific content. All authors have contributed to prepare and they approved the final manuscript

![(A) Hypochromatic, hypo-anesthetic macule on the left upper limb; (B) Areas with loss of tactile sensitivity [green dashed area = 0.07 gram-force (normal threshold of tactile sensitivity); blue dashed area = 0.2 g-f; purple dashed area = 2.0 g-f; red dashed area = 4.0 g-f]; (C-D) improvement of tactile sensitivity after five months of multibacillary multidrug therapy.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/14138670/0000002500000005/v1_202110310703/S1413867021001033/v1_202110310703/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w95uaF0+42b+pWE4hY44gaZY=)