Members of the genus Myroides are aerobic Gram-negative bacteria that are common in environmental sources, but are not components of the normal human microflora. Myroides organisms behave as low-grade opportunistic pathogens, causing infections in severely immunocompromised patients and rarely, in immunocompetent hosts. A case of Myroides odoratimimus cellulitis following a pig bite in an immunocompetent child is presented, and the medical literature on Myroides spp. soft tissue infections is reviewed.

Myroides species, formerly classified as Flavobacteriun odoratum, are Gram-negative, nonfermentative, obligately aerobic, yellow-pigmented, and non-motile rods, with a characteristic fruity odor. The genus Myroides comprises two species, Myroides odoratus and Myroides odoratimimus.1 Although commonly found in soil and water, Myroides spp. are rare clinical isolates and are often not considered pathogenic. The organism has been isolated from urine, blood, wounds, and respiratory secretions.2,3 Clinical infection with Myroides spp. is exceedingly rare; however, cases of endocarditis, ventriculitis, and soft tissue infections, and two outbreaks, one of urinary tract infection and the other of central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection due to contaminated water, have been reported.4–13

A case of Myroides odoratimimus cellulitis following a pig bite, in an immunocompetent child, is reported, and the English medical literature on confirmed Myroides spp. soft tissue infections is reviewed.

Case presentationA 13-year-old male was admitted to the pediatric emergency unit because of the deterioration of a wound on his right tibia, accompanied by elevated fever. Sixty hours earlier a pig had bitten the boy on the upper third of his right tibia, causing an approximately 3 cm-wide lacerated wound. The wound was cleansed and sutured in the emergency department of the regional hospital and the boy was treated empirically with oral cefuroxime and metronidazole. Despite this therapy, during the following days the injury progressively deteriorated and presented a purulent secretion.

Upon clinical examination his temperature was 39°C and the wound presented signs of cellulitis. Regional lymphadenopathy or lymphangitis were not detected. Laboratory tests revealed elevated peripheral WBC count of 11,700/mm3 (neutrophils 75%), and inflammatory markers were also increased (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ERS] 49mm/h, and a C-reactive protein elevated at 9.36mg/dL [normal value: 0.08-0.8mg/dL]).

Two different swab specimens of purulent material were collected and sent for culture, prior to the administration of empiric antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam 2.2mg/6h IV and clindamycin 600mg/8h IV).

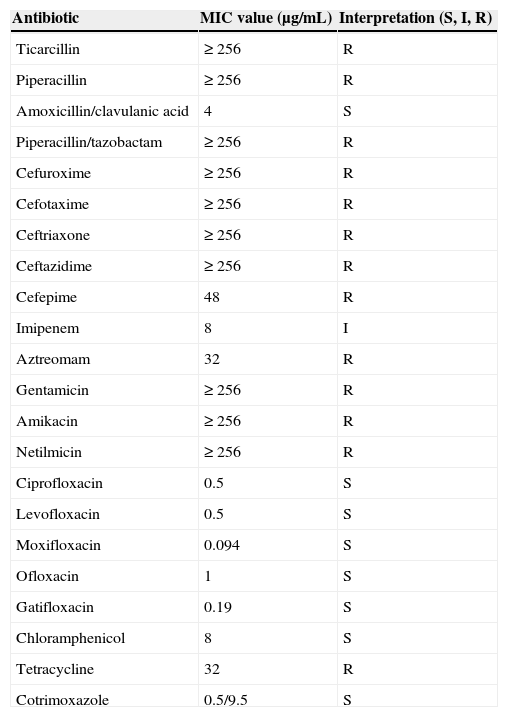

The pus culture yielded a Gram-negative rod, eventually identified as Myroides odoratimimus (conventional and molecular typing). The in vitro susceptibility testing of the isolate proved it resistant to piperacillin/tazobactam, aztreonam, aminoglycosides, intermediately susceptible to imipenem, and susceptible to all quinolones tested, cotrimoxazole, chloramphenicol, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Table 1). Based on the results of the susceptibility testing, the piperacillin/tazobactam was switched to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1.25g/8h IV.

In vitro susceptibility of the Myroides odoratimimus isolate.

| Antibiotic | MIC value (μg/mL) | Interpretation (S, I, R) |

|---|---|---|

| Ticarcillin | ≥ 256 | R |

| Piperacillin | ≥ 256 | R |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 4 | S |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | ≥ 256 | R |

| Cefuroxime | ≥ 256 | R |

| Cefotaxime | ≥ 256 | R |

| Ceftriaxone | ≥ 256 | R |

| Ceftazidime | ≥ 256 | R |

| Cefepime | 48 | R |

| Imipenem | 8 | I |

| Aztreomam | 32 | R |

| Gentamicin | ≥ 256 | R |

| Amikacin | ≥ 256 | R |

| Netilmicin | ≥ 256 | R |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | S |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | S |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.094 | S |

| Ofloxacin | 1 | S |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.19 | S |

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | S |

| Tetracycline | 32 | R |

| Cotrimoxazole | 0.5/9.5 | S |

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

On the seventh hospitalization day, given the absence of improvement and persistence of an elevated ESR of 49mm/h, an MRI of the right tibia was performed, which revealed osteolytic lesions on the medial condyle of the right tibia. The patient was transferred to surgery and a drain on the right tibia was positioned. On the second day post-surgery, ciprofloxacin 400mg/12h IV was added to the therapeutic regimen, and on the third day post-surgery, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was discontinued. The patient received intravenous ciprofloxacin for ten days and continued with oral ciprofloxacin for an additional ten days.

Gradually, the patient's clinical condition improved and laboratory values returned to normal. The patient was finally discharged on the 13th post-surgery day, in a good physical condition.

DiscussionAnimal attacks on people all over the world result in million of injuries, deaths, and a large economic expense. It is estimated that in the United States the cost from injuries and fatalities due to animals is over 2 billion dollars annually.14 Information on animal-related injuries and specifically on the biting injuries from pigs and the infections that develop from them, is lacking in Greece.

Several cases of pig bite wound infections, most frequently cellulitis with abscess formation, have been described.15–18 A variety of microorganisms such as Pastereulla spp., Actinobacillus spp., Streptococcus spp. and Staphylococcus aureus, which are commensal oropharyngeal flora, have been implicated in wound infections following pig bites.15–17 In 1990, Goldstein et al. reported the isolation of a Flavobacterium-like organism from a hand infection following a pig bite.18 The present case represents the first case of Myroides odoratimimus pig bite wound infection.

Since the spectrum of pig bite pathogens is broad and could include unusual bacteria, cultures must be always considered in pig bite wounds to guide therapy.

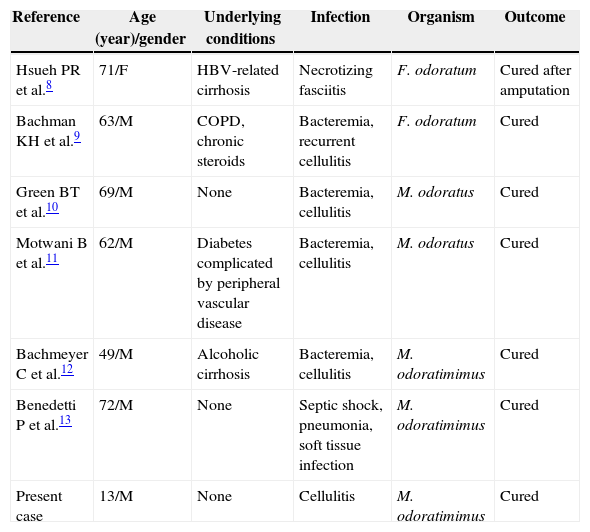

In 1979, Holmes et al. reported 24 cases of isolation of Flavobacterium odoratum, and the infection was only suspected in five of them.2 In one case, the organism was isolated from an amputation stump, and in another, from the skin of gangrenous feet.2 Soft tissue infection was well established in six previous cases: cellulitis associated with bacteremia in four patients, soft tissue infection with septic shock and pneumonia in one patient, and necrotizing fasciitis in another patient8–13 (Table 2).

Cases of Myroides spp. soft-tissue infections.

| Reference | Age (year)/gender | Underlying conditions | Infection | Organism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsueh PR et al.8 | 71/F | HBV-related cirrhosis | Necrotizing fasciitis | F. odoratum | Cured after amputation |

| Bachman KH et al.9 | 63/M | COPD, chronic steroids | Bacteremia, recurrent cellulitis | F. odoratum | Cured |

| Green BT et al.10 | 69/M | None | Bacteremia, cellulitis | M. odoratus | Cured |

| Motwani B et al.11 | 62/M | Diabetes complicated by peripheral vascular disease | Bacteremia, cellulitis | M. odoratus | Cured |

| Bachmeyer C et al.12 | 49/M | Alcoholic cirrhosis | Bacteremia, cellulitis | M. odoratimimus | Cured |

| Benedetti P et al.13 | 72/M | None | Septic shock, pneumonia, soft tissue infection | M. odoratimimus | Cured |

| Present case | 13/M | None | Cellulitis | M. odoratimimus | Cured |

Except for two cases that have been described in immunocompetent individuals, Myroides species usually affect immunocompromised hosts, such as those with liver cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on long-term corticosteroid treatment.8–13 The present case is the first soft tissue infection caused by Myroides reported in an immunocompetent child.

On several occasions the invasive potential of Myroides species by spreading from the cutaneous site of origin to the bloodstream has been demonstrated.8–10 In the present patient, the organism from the skin penetrated and caused osteolytic lesions on the right tibia.

Antibiotic treatment is currently problematic because most strains are resistant to β-lactams, monobactams, carbapenems, and aminoglycosides.2 It has been shown that resistance to β-lactams is due to the production of chromosome-encoded metallo-β-lactamases (TUS-1 and MUS-1).19 Clinical isolates are usually susceptible to quinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and clinical cure has been observed in several cases when ciprofloxacin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were administered.4,5,8,9 The strain isolated from this patient was also multiresistant and treatment with ciprofloxacin, based on the susceptibility test, was required for cure. For this reason, antimicrobial susceptibility testing is recommended in all isolates, to provide clinical guidance in the selection of the appropriate antimicrobial agent.

Myroides species should be included in the differential diagnosis of skin and soft tissue infections in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts, especially when the patient is not responding to routine antimicrobial treatment.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare to have no conflict of interest.