Sexually transmitted diseases are still highly prevalent worldwide and represent an important public health problem. Psychiatric patients are at increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases but there are scarce published studies with representative data of this population. We sought to estimate the prevalence and correlates of self-reported sexually transmitted diseases among patients with mental illnesses under care in a national representative sample in Brazil (n=2145). More than one quarter of the sample (25.8%) reported a lifetime history of sexually transmitted disease. Multivariate analyses showed that patients with a lifetime sexually transmitted disease history were older, had history of homelessness, used more alcohol and illicit drugs, suffered violence, perceived themselves to be at greater risk for HIV and had high risk sexual behavioral: practised unprotected sex, started sexual life earlier, had more than ten sexual partners, exchanged money and/or drugs for sex and had a partner that refused to use condom. Our findings indicate a high prevalence of self-reported sexually transmitted diseases among psychiatric patients in Brazil, and emphasize the need for implementing sexually transmitted diseases prevention programs in psychiatric settings, including screening, treatment, and behavioral modification interventions.

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are still highly prevalent worldwide. According to the 2005 World Health Organization (WHO) estimates,1 448 million new cases of curable STDs (e.g., syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis) occur annually throughout the world, not including HIV and other STDs (like herpes or hepatitis), and, among these, 50 million cases occur in the Americas.1

In 2005, the Brazilian Ministry of Heath evaluated the prevalence of STDs on three different populations in six Brazilian capitals: pregnant women, male workers from small industries (both considered to be at an average risk for STDs), and patients from an STD clinic (male and female sample of a group regarded as having a high-risk sexual behavior).3 The prevalence of at least one STD in each of these three populations was, respectively, 42.0%, 5.2% and 51.0%. The prevalence of STDs was higher among younger age groups (20 years old or less), among those with multiple partners, who practised unsafe sex, anal sex, and in those who used injected drugs. In another national survey,4 35.6% of truck drivers reported a lifetime history of STD and, relative to those without STD history, they were older, consumed more illicit drugs, had been incarcerated more often, and had more sex with sex workers.

STDs also represent an important public health problem due to their complications such as neonatal syphilis – which may result in stillbirth, neonatal death or malformation1; cervical cancer caused by human papilloma virus (HPV)5; and pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility due to Chlamydia.5 In addition, STDs, especially genital ulcerative diseases, can facilitate transmission and acquisition of HIV.6 A study7 using anonymous HIV testing and counseling program, conducted in Taiwan from 2006 to 2010, showed 10.7% of participants with at least one STD and 3.5% with HIV in that sample. In the same study, the HIV prevalence was 14.7% among patients with previous STDs, while among those without STDs history it was only 3.0%.7

Patients with chronic mental illness are at increased risk of STDs and present elevated rates of high risk sexual behavior.8 A national sample of psychiatric patients in Brazil9 demonstrated that these patients are sexually active at rates that are similar to those of the overall adult Brazilian population.10 Furthermore, only 16.0% of these psychiatric patients used condoms in the last six months, in comparison to 20.6% among estimates for the overall Brazilian adults during the last year.11 In addition, the use of psychoactive drugs was higher among psychiatric patients compared to the general population, 25.1%9 and 8.9%,12 respectively. In the same sample of psychiatric patients,9 unprotected sexual behavior was associated with having sex under the influence of alcohol and having multiple sexual partners.

However, there are few published studies addressing STDs among patients with psychiatric illnesses.13 A systematic review indicated that most of the published studies on this population are from developed countries and are based on relatively small and non-representative samples.14 The prevalence of selected STDs among psychiatric patients varied from 0.8% to 29.0% for HIV; from 1.6% to 66.0% for Hepatitis B; from 0.4% to 38.0% for Hepatitis C; and from 1.1% to 7.6% for syphilis.14 Over one-third (38.0%) of a sample of patients from two American psychiatric hospitals reported a lifetime history of one or more STDs.15 HIV-related knowledge, greater self-perceived HIV risk, higher intention to use condom and higher rates of unprotected vaginal and anal sex emerged as significant correlates of a prior STD.

The objective of this study was to estimate the prevalence and correlates of lifetime self-reported STDs among patients with mental illnesses under care in a national representative sample in Brazil.

Materials and methodsStudy design and participantsThe sample for the current analysis was drawn from a larger national multicenter cross-sectional study conducted in 11 public psychiatric hospitals and 15 public mental health outpatient clinics (CAPS) in Brazil in 2006, designed to assess risk behavior and sexually transmitted infections/HIV prevalence in a national representative sample of patients with chronic mental illnesses under care (n=2475) previously described.16,17 Briefly, participants had be 18 years old or over and be capable of providing written informed consent.

A preliminary assessment was carried out by mental health professionals in order to evaluate the subjects’ capacity to participate and sign the consent form – those with delusional symptoms, acute psychosis and a severe degree of mental retardation were not eligible. Ethical approval was obtained from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG/ETIC 125/03) and the National Ethical Review Board (CONEP 592/2006), and all participants signed written informed consent. For the current analysis, only those participants who reported being sexually active at least once in life were included (n=2145).

Data collectionA semi-structured person-to-person interview was conducted using a previously tested and validated questionnaire.17 It was administered by experienced and trained mental health care professionals and aimed at obtaining sociodemographic, clinical and behavioral data. The main outcome in this analysis was lifetime self-reported history of STDs and it was assessed with the question: “Have you had any disease transmitted through sexual intercourse or venereal disease?”. Additional questions were asked regarding three main syndromic groups (genital/anal ulcerative diseases, warts, and discharge) and specific STD medical diagnoses (e.g. syphilis, herpes, chancroid, chlamydia, gonorrhea, lymphogranuloma venereum, and condyloma).

Good to excellent reliability (intra and inter-rater) was found for all self-reported data used in the present analysis, including being sexually active (kappa=0.76) and having an STD history (kappa=0.70).18

Explanatory variables included in this analysis were: sociodemographic data (e.g. age, gender, skin color, marital status, schooling, family income, living situation, history of homelessness); clinical characteristics (e.g. type of recruitment center, psychiatric diagnosis, STD history, previous psychiatric hospitalization, previous HIV testing); and, behavioral data (e.g. lifetime tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug and injection drug use, sex under the influence of alcohol/drugs, lifetime unprotected sex, having a partner that refused to use condom, exchanging money/drugs for sex, number of sexual partners, age at first sexual intercourse, lifetime verbal physical or sexual violence, lifetime incarceration, HIV/AIDS knowledge, and self-perception of HIV risk).

Psychiatric diagnoses were obtained from medical charts and were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases-10th Edition (ICD-10). When more than one psychiatric diagnosis was present, these were hierarchically grouped according to clinical severity as follows: (1) schizophrenia (and other psychotic disorders), depression with psychotic symptoms and bipolar disorder; (2) depression, anxiety and others (3) substance use disorder. Living conditions at the time of the interview were defined as stable, when participants reported living in houses, apartments, or hospitals, or unstable, when participants reported living on the streets, public shelters, garages, rooms or other ill-defined places. Condom use was assessed as always, sometimes (more than 50% of the time), rarely (less than 50% of the time), and never. For this analysis, unprotected sex was defined as not always using condoms in all sexual practices during lifetime. HIV/AIDS knowledge was assessed through 10 true or false questions and good knowledge was defined as having eight or more correct answers. These statements have been used in prior studies and were derived from Brazilian population-based studies.19,20 Self-perception of HIV risk was categorized as high or some, no risk, and did not know.

Statistical analysisThe prevalence of lifetime self-reported STDs was expressed as a percentage and it was calculated as the number of participants with prior history of STD divided by the total number of patients included in this analysis. Descriptive analysis was carried out and Chi-square statistic was used to assess differences of categorical data. The magnitude of the associations between explanatory variables and the outcome of interest – history of STD – was estimated by the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The independent effect of potential exposure variables was assessed by multivariate analysis using logistic regression. All variables with p-values equal to or less than 0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in multivariate modeling. A backward deletion strategy was applied and those variables with p-values equal to or less than 0.05 remained in the final model. SAS System® was used for data analysis and Paradox® Windows for the database management.

ResultsAmong the 2475 patients interviewed, 2145 (86.7%) were sexually active (ever) and were included in this analysis. Among these, most participants were under treatment in outpatient centers (CAPS) (64.7%), older than 40 years old (55.5%), white (51.5%), female (52.6%), and 62.3% were single, divorced or widowed (Table 1). Almost half of the sample had less than five years of schooling (48.3%) and for 18.0% of patients the family income was lower than the Brazilian minimum wage at the time of the interview (

Descriptive characteristics among the 2145 eligible psychiatric patients.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |

| Age (>40 years old) | 1190 (55.5) |

| Skin color (white) | 1105 (51.5) |

| Gender (female) | 1129 (52.6) |

| Marital status (single, divorced or widowed) | 1337 (62.3) |

| Schooling (<5 years) | 1036 (48.3) |

| Family income (<1 minimum wagea) | 305 (18.0) |

| Living in unstable situationb | 84 (3.9) |

| Lifetime homelessness | 397 (18.5) |

| Clinical | |

| Type of recruitment center | |

| CAPS | 1387 (64.7) |

| Hospital | 758 (35.3) |

| Previous psychiatric hospitalization | 1228 (57.5) |

| Main psychiatric diagnosis | |

| Psychoses, DPS, BPD | 1197 (55.8) |

| Substance use | 169 (7.9) |

| Others | 779 (36.3) |

| Previous HIV testing | 646 (30.1) |

| Behavioral | |

| Lifetime cigarette smoking | 1574 (73.6) |

| Lifetime alcohol use | 1461 (68.1) |

| Lifetime illicit drug use | 599 (27.9) |

| Lifetime injection drug use | 70 (3.3) |

| Sex under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs | 672 (31.6) |

| Lifetime unprotected sexc | 1944 (91.6) |

| Partner refused to use condom anytime | 588 (28.2) |

| Exchange money and/or drugs for sex | 642 (30.1) |

| Number of sexual partners | |

| Only one | 496 (24.8) |

| 2–9 | 969 (48.4) |

| 10 or more | 536 (26.8) |

| Age of first sexual intercourse (years old) | |

| <14 | 306 (15.0) |

| 14–18 | 1125 (55.0) |

| >18 | 616 (30.0) |

| Lifetime verbal violence | 1533 (71.6) |

| Lifetime physical violence | 1279 (59.8) |

| Lifetime sexual violence | 460 (21.6) |

| Lifetime incarceration | 584 (27.2) |

| Good HIV/AIDS knowledge | 1249 (58.6) |

| High HIV risk self-perception | 415 (20.1) |

DPS, depression with psychotic symptoms; BPD, bipolar disorder.

More than one quarter of the participants (25.8%) reported a history of STD. Lifetime STD symptoms, characterized in three main syndromic groups, were genital discharges (35.8%), genital ulcers (14.2%), and warts (7.6%). Four percent of the participants received a medical diagnosis of syphilis, 3.7% of herpes, 2.4% of chancroid, 10.7% of gonorrhea, 3.1% of chlamydia, 0.8% of lymphogranuloma, and 3.2% of condyloma (Table 2).

Characteristics and prevalence of lifetime sexually transmitted diseases among the 2145 eligible psychiatric patients.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Self-reported STDa | 554 (25.8) |

| Syndromic groups | |

| Genital discharge | 761 (35.8) |

| Genital ulcers | 301 (14.2) |

| Genital warts | 161 (7.6) |

| Medical diagnosis | |

| Syphilis | 79 (3.8) |

| Herpes | 79 (3.7) |

| Chancroid | 50 (2.4) |

| Gonorrhea | 227 (10.7) |

| Chlamydia | 66 (3.1) |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | 16 (0.8) |

| Condyloma | 67 (3.2) |

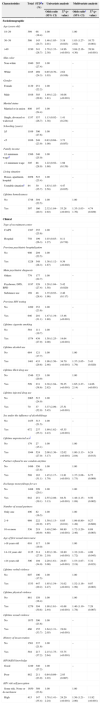

Univariate analysis (Table 3) indicated that the prevalence of self-reported STD was almost two fold higher among men and among those over 40 years old (p<0.001). The odds ratio of self-reported STD was two times higher for those living on the streets or in public shelters than among those living in houses, apartments or hospitals. Also, a previous history of homelessness was statistically associated with past STD. The participants who had a previous psychiatric hospitalization and those who were tested for HIV were more likely to have an STD history (p<0.002). Likewise, the use of cigarette, alcohol, illicit drugs and injected drugs were statistically associated with self-reported STD. Several high risk sexual behavior characteristics were also associated with STD history (p<0.001), as follows: sex under the influence of alcohol/drugs, previous unprotected sex, partner refusing to use condom and receiving or offering money/drugs for sex. In addition, the odds ratio of STD history was more than three times higher among those with 10 or more sexual partners and more than two times higher among those who had their first sexual intercourse before 14 years old. Moreover, patients with a history of verbal, physical or sexual violence and those with past incarceration were also more likely to report previous STD (p<0.001). Finally, the univariate analysis indicated that the prevalence of self-reported STDs was higher among patients who perceived themselves as being at high risk for HIV/AIDS (p<0.001).

Univariate and multivariate logistic analysis of self-reported STDa among the 2145 eligible psychiatric patients.

| Characteristics | Total | STDbn (%) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | X2 (p-value) | Odds ratioc (95% CI) | X2 (p-value) | |||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Age (years old) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 369 | 68 (18.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 30–39 | 586 | 145 (24.7) | 1.46 (1.05–2.01) | 5.18 (0.023) | 1.83 (1.27–2.62) | 10.75 (0.001) |

| >40 | 1190 | 341 (28.7) | 1.78 (1.33–2.38) | 14.96 (<0.001) | 3.04 (2.16–4.30) | 39.94 (<0.001) |

| Skin color | ||||||

| Non-white | 1040 | 285 (27.4) | 1.00 | – | ||

| White | 1105 | 269 (24.3) | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 2.62 (0.106) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1129 | 251 (22.2) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Male | 1016 | 303 (29.8) | 1.49 (1.22–1.81) | 16.08 (<0.001) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married or in union | 808 | 197 (24.4) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Single, divorced or widowed | 1337 | 357 (26.7) | 1.13 (0.92–1.38) | 1.41 (0.234) | ||

| Schooling (years) | ||||||

| ≥5 | 1109 | 306 (27.6) | 1.00 | – | ||

| <5 | 1036 | 248 (23.9) | 0.83 (0.68–1.00) | 3.73 (0.053) | ||

| Family income | ||||||

| ≥1 minimum waged | 1386 | 346 (25.0) | 1.00 | – | ||

| <1 minimum wage | 305 | 88 (28.9) | 1.22 (0.92–1.60) | 1.98 (0.159) | ||

| Living situation | ||||||

| House, apartment, hospital | 2058 | 523 (25.4) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Unstable situatione | 84 | 30 (35.7) | 1.63 (1.03–2.58) | 4.47 (0.035) | ||

| Lifetime homelessness | ||||||

| No | 1748 | 394 (22.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 397 | 160 (40.3) | 2.32 (1.84–2.92) | 53.28 (<0.001) | 1.35 (1.03–1.76) | 4.74 (0.029) |

| Clinical | ||||||

| Type of recruitment center | ||||||

| CAPS | 1387 | 355 (25.6) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Hospital | 758 | 199 (26.3) | 1.03 (0.85–1.27) | 0.11 (0.739) | ||

| Previous psychiatric hospitalization | ||||||

| No | 908 | 204 (22.5) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1228 | 348 (28.3) | 1.36 (1.12–1.67) | 9.39 (<0.002) | ||

| Main psychiatric diagnosis | ||||||

| Others | 779 | 177 (22.7) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Psychoses, DPS, BPD | 1197 | 328 (27.4) | 1.28 (1.04–1.58) | 5.42 (0.020) | ||

| Substance use | 169 | 48 (28.4) | 1.35 (0.93–1.96) | 2.46 (0.117) | ||

| Previous HIV testing | ||||||

| No | 1499 | 353 (23.6) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Yes | 646 | 201 (31.1) | 1.47 (1.19–1.80) | 13.48 (<0.001) | ||

| Lifetime cigarette smoking | ||||||

| No | 564 | 111 (19.7) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Yes | 1574 | 439 (27.9) | 1.58 (1.25–2.00) | 14.64 (<0.001) | ||

| Lifetime alcohol use | ||||||

| No | 684 | 121 (17.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1461 | 433 (29.6) | 1.96 (1.56–2.46) | 34.70 (<0.001) | 1.37 (1.05–1.79) | 5.43 (0.020) |

| Lifetime illicit drug use | ||||||

| No | 1546 | 323 (20.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 599 | 231 (38.6) | 2.38 (1.94–2.92) | 70.35 (<0.001) | 1.65 (1.27–2.14) | 14.06 (<0.001) |

| Lifetime injected drug use | ||||||

| No | 2065 | 515 (24.9) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Yes | 70 | 37 (52.9) | 3.37 (2.09–5.45) | 27.51 (<0.001) | ||

| Sex under the influence of alcohol/drugs | ||||||

| No | 1455 | 313 (21.5) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Yes | 672 | 237 (35.3) | 1.99 (1.62–2.43) | 45.35 (<0.001) | ||

| Lifetime unprotected sexf | ||||||

| No | 179 | 27 (15.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1944 | 524 (27.0) | 2.08 (1.36–3.17) | 12.02 (<0.001) | 1.80 (1.13–2.84) | 6.24 (0.013) |

| Partner refused to use condom anytime | ||||||

| No | 1496 | 356 (23.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 588 | 183 (31.1) | 1.45 (1.17–1.79) | 11.81 (<0.001) | 1.37 (1.08–1.73) | 6.75 (0.009) |

| Exchange money/drugs for sex | ||||||

| No | 1488 | 299 (20.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 642 | 251 (39.1) | 2.55 (2.08–3.13) | 84.51 (<0.001) | 1.48 (1.15–1.89) | 9.56 (0.002) |

| Number of sexual partners | ||||||

| Only one | 496 | 82 (16.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2–9 | 969 | 222 (22.9) | 1.50 (1.13–1.97) | 8.05 (0.011) | 1.09 (0.80–1.49) | 0.27 (0.600) |

| 10 or more | 536 | 219 (40.9) | 3.49 (2.60–4.68) | 69.89 (<0.001) | 1.72 (1.20–2.46) | 8.88 (0.003) |

| Age of first sexual intercourse | ||||||

| >18 years old | 616 | 117 (19.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 14–18 years old | 1125 | 314 (27.9) | 1.65 (1.30–2.10) | 16.80 (<0.001) | 1.32 (1.01–1.72) | 4.08 (0.043) |

| <14 years old | 306 | 104 (34.0) | 2.20 (1.61–3.00) | 24.63 (<0.001) | 1.53 (1.07–2.19) | 5.32 (0.021) |

| Lifetime verbal violence | ||||||

| No | 607 | 106 (17.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1533 | 447 (29.2) | 1.95 (1.54–2.47) | 31.02 (<0.001) | 1.52 (1.16–1.99) | 9.07 (0.003) |

| Lifetime physical violence | ||||||

| No | 861 | 158 (18.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1279 | 394 (30.8) | 1.98 (1.61–2.44) | 41.68 (<0.001) | 1.40 (1.10–1.78) | 7.28 (0.007) |

| Lifetime sexual violence | ||||||

| No | 1675 | 396 (23.6) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Yes | 460 | 155 (33.7) | 1.64 (1.31–2.05) | 19.04 (<0.001) | ||

| History of incarceration | ||||||

| No | 1561 | 337 (21.6) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Yes | 584 | 217 (37.2) | 2.15 (1.75–2.64) | 53.75 (<0.001) | ||

| HIV/AIDS knowledge | ||||||

| Good | 1249 | 340 (27.2) | 1.00 | – | ||

| Poor | 882 | 211 (23.9) | 0.84 (0.69–1.03) | 2.93 (0.087) | ||

| HIV risk self-perception | ||||||

| Some risk. None or do not know | 1650 | 389 (23.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| High | 415 | 147 (35.4) | 1.78 (1.41–2.24) | 24.20 (<0.001) | 1.56 (1.21–2.00) | 11.92 (<0.001) |

DPS, depression with psychotic symptoms; BPD, bipolar disorder.

The multivariate analysis (Table 3) indicated 12 variables which were independently associated (p<0.05) with self-reported STD: being 30–39 years old and older than 40 years old; history of homelessness; lifetime alcohol or illicit drugs use; lifetime unprotected sex; partners’ refusal to use condom at least once; exchanging money/drugs for sex; having more than 10 sexual partners; early age of first sexual intercourse (<14 years old and between 14 and 18 years old); history of verbal or physical violence; and those who perceived themselves as being at high risk for HIV/AIDS.

DiscussionOur results indicate that more than a quarter (25.8%) of participants in this national representative sample of psychiatric patients under care in Brazil had a lifetime history of at least one STD. This result is of public health concern and it is corroborated by other studies among psychiatric patients. In a study of patients with chronic mental illnesses, designed to assess the efficacy of an intervention for HIV prevention, in the USA, the prevalence of self-reported STD was 38%.15 However, their sample was only hospital-based and with psychiatric patients with substance use disorders, which can partially explain their higher proportion of history of STD. King et al.21 demonstrated 40.4% of self-reported STD among patients attending an outpatient university-based psychiatric clinic which included diverse psychiatric diagnoses in USA. Studies carried out in India among psychiatric patients seeking care for substance use disorder22 and among patients hospitalized in a general psychiatric hospital23 found STD rates of 25.1% and 16.2%, respectively. Both studies used serologic tests to investigate syphilis, chlamydia, HIV and hepatitis B.

The prevalence of previous STD found in our study is high when compared with other Brazilian non-psychiatric populations. Many authors studied the prevalence of STDs in the general population, ranging from 5.2% to 21.3%.3,24,25 Among pregnant women the prevalence of STDs ranged from 6.7% to 42.0%.3,26 Population with well-known higher risk sexual behavior were assessed and STDs prevalence ranged from 22.0% to 51.0% when clients of STD clinics were studied.3,27

It should be pointed out the difficulty in comparing data across studies that vary widely in their sampling and assessment methods. Nonetheless, it is important to notice that the prevalence of STDs was higher when compared to our study only when the population studied had well-known higher risk sexual behavior, such as STD clinics clients, or when serologic testing for STD increased the detection rates of the addressed population.

Our study identified several factors associated with history of STD among this representative sample of psychiatric patients. These factors may serve as potential indicators of risk behaviors suitable to preventive actions in these services. The prevalence of self-reported STD was higher among those older than 30 years old. In contrast to higher risk of STD among younger populations described by other authors,2,3 the association found with older age groups in our study can be explained by a lifetime cumulative exposure, usually detected in prevalence as opposed to incidence studies. A similar result was found in a study conducted among 641 truck drivers in Brazil.4 As demonstrated by other studies, substance use is a strong predictor of STD in several populations, including patients with mental illnesses.4,22,24,27 Carey et al.22 demonstrated that psychiatric patients in risk for alcohol and drug abuse had higher prevalence of STDs. In a controlled trial28 addressing HIV prevention, patients who received a substance use reduction intervention were more likely than controls to reduce the number of sexual partners and to endorse stronger intention to use condoms. In our study, alcohol and illicit drug use were independently associated with STD history, while use of tobacco and injected drugs was only found to be associated in univariate analysis. The association of substance use with STD can be explained by poor access to prevention and care and also due to a potential impairment of judgment to practise safe sex, which may lead to poor decisions regarding sexual behavior. Effective alcohol and drug prevention and treatment may reduce sexual risk behavior, and consequently the STDs prevalence.

We have also identified important behavioral factors associated with an increased likelihood of STDs: lifetime unprotected sex, partner's refusal to use condom, exchanging money and/or drugs for sex, having multiple sexual partners, and early age of first sexual intercourse. High risk sexual behaviors among patients with mental illnesses have been highlighted by other investigators. Vanable et al.15 found that patients with mental illness receiving care in a hospital with a previous STD practised unprotected sex more often. Carey et al.,23 also studying psychiatric inpatients, indicated that lifetime STD was statistically associated with exchanging money for sex and having multiples partners. King et al.21 demonstrated that STD was associated with exchanging sex for drugs in a sample of psychiatric outpatients in USA. This high risk sexual behavior was also described in Brazil, in a sample of patients of a psychiatric hospital in the Southeast Region,29 where 68.2% of patients had previous unprotected sex and 2.6% exchanged sex for money or drugs.

In addition to behavioral and substance use correlates, our data also point out the increased social vulnerability profile of these psychiatric patients, including suffering violence and presenting higher rates of homelessness. Those who reported having suffered verbal and physical violence, and those with a history of homelessness had statistically higher proportions of STDs. Our findings are consistent with recent data published by Oliveira30 which indicates that verbal and physical violence against women and men were independently associated with a previous diagnosis of STD among psychiatric patients. In addition, suffering violence was also associated with lifetime homelessness in the same study. People living with mental illnesses are frequently exposed to many factors that leave them in extreme vulnerable conditions, especially those who have experienced homelessness situations. They are often subject to violence, and are more prone to alcohol and drug abuse as well as exchanging sex as a means of obtaining food, shelter, money or drugs. All these factors exacerbate the already fragile individuals and it certainly leaves them more exposed to STDs.

On the other hand, patients who perceived themselves at a higher risk for acquisition of HIV presented higher prevalence of history of STD. This result may actually reflect a dynamics between risk behavior, HIV awareness, and the perception of need and access to care. As proposed by other authors,15 it seems that diagnosis and treatment of STDs may increase HIV-related awareness and knowledge, but they do not necessarily lead to changes in sexual risk behavior. This is consistent with our data, since in our sample, patients with a STD history reported higher rates of sexual risk behavior in comparison to the patients without a previous STD history.

Our study has some limitations: STDs were self-reported, and since they are often asymptomatic, it could lead to a potential underestimation of their prevalence. However, the proportion found was considerably high, which actually reinforces the magnitude of the problem. In addition, reliability of the data was adequate as shown.18 Also, because this is a cross-sectional study, we can only indicate statistical correlations rather than direct causal effect between potential explanatory variables and a history of STDs. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with the literature and have important clinical and public health implications.

In conclusion, as shown, most factors associated with STDs among this representative sample of patients with mental illnesses in Brazil are potentially modifiable behavioral factors. As patients are admitted for care in these mental health services, a good opportunity for STD and risk behavioral screening is created. Although programs designed to integrate STD prevention with the psychiatric care have been successfully implemented,28 only eight (31.0%) of the 26 centers included in our study had specific educational programs for STDs,31 indicating a clear lack of opportunity for prevention and care for STDs. Screening for STDs, including HIV, hepatitis B and C, and syphilis should be part of the routine care in these centers. In addition, counseling, behavioral modification intervention and referral for treatment and follow-up of those with positive results should be implemented on a routine basis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was carried out by the Federal University of Minas Gerais with technical and financial support of the Ministry of Health/Secretariat of Health Surveillance/Department of STD, AIDS and Viral Hepatitis through the Project of International Technical Cooperation 914/BRA/1101 between the Brazilian Government and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization – UNESCO.