Sepsis is one of the major causes of death and is the biggest obstacle preventing improvement of the success rate in curing critical illnesses. Currently, isotonic solutions are used in fluid resuscitation technique. Several studies have shown that hypertonic saline applied in hemorrhagic shock can rapidly increase the plasma osmotic pressure, facilitate the rapid return of interstitial fluid into the blood vessels, and restore the effective circulating blood volume. Here, we established a rat model of sepsis by using the cecal ligation and puncture approach. We found that intravenous injection of hypertonic saline dextran (7.5% NaCl/6% dextran) after cecal ligation and puncture can improve circulatory failure at the onset of sepsis. We found that the levels of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, interleukin-6 and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 levels in the lung tissue of cecal ligation and puncture rats treated with hypertonic saline dextran were significantly lower than the corresponding levels in the control group. We inferred that hypertonic saline dextran has a positive immunoregulatory effect and inhibits the overexpression of the inflammatory response in the treatment of sepsis. The percentage of neutrophils, lung myeloperoxidase activity, wet to dry weight ratio of lung tissues, histopathological changes in lung tissues, and indicators of arterial blood gas analysis was significantly better in the hypertonic saline dextran-treated group than in the other groups in this study. Hypertonic saline dextran-treated rats had significantly improved survival rates at 9 and 18h compared to the control group. Our results suggest that hypertonic saline dextran plays a protective role in acute lung injury caused after cecal ligation and puncture. In conclusion, hypertonic/hyperoncotic solutions have beneficial therapeutic effects in the treatment of an animal model of sepsis.

Infection and sepsis cause a very high disease rate and morbidity in patients with critical illness. Clinical epidemiological data have revealed that sepsis is one of the major causes of death in critical patients and has become the biggest obstacle in the success rate for curing high-risk diseases.1 Obtaining a better understanding of severe infectious complications and their prevention and treatment are undoubtedly of considerable theoretical value and clinical significance. The pathogenesis of sepsis is very complicated. It is difficult to treat, and involves a series of basic problems such as infection, inflammation, immunity, blood coagulation, and tissue injury; furthermore, it is associated with pathophysiological changes in multiple body systems and organs.

Recent studies have made considerable progress on the onset and clinical significance of sepsis. However, no results have shed light on the anti-inflammatory treatment of sepsis and multi-organ dysfunction (MODS) syndrome. Currently, the standard fluid used in fluid resuscitation is an isotonic solution such as 0.9% NaCl solution and lactated Ringer's solution. Many studies have shown that hypertonic/hyperoncotic solutions used for fluid resuscitation can rapidly increase the plasma osmotic pressure, enable the interstitial fluid to return to the blood vessels rapidly and thereby restore the effective circulating blood volume,2,3 and provide therapeutic effects for pulmonary edema caused by hemorrhagic shock.4 Zallen et al.5 reported that hypertonic saline can improve hemodynamic disorders in hemorrhagic shock, prevent neutrophil activation, and inhibit ICAM-1 expression by migrating through the intestinal lymphatic pathway. Junger et al.6 found that hypertonic saline used for resuscitation in hemorrhagic shock can inhibit neutrophil and endothelial cell activation. These studies suggest that hypertonic saline can function in immune regulation during resuscitation from shock. However, doubts remain about its usefulness for the treatment of sepsis. In the present study, we developed a rat model of sepsis using the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) approach to investigate the influence of hypertonic/hyperoncotic solutions on mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate, their potential role in the regulation of serum inflammatory cytokines, and their influence on lung tissue apoptosis and tissue ICAM-1 expression in septic rats and to discuss their potential therapeutic effects in the treatment of sepsis.

Materials and methodsEstablishment of a rat sepsis modelIn total, 128 male Wistar rats (10–12 weeks old, weight: 230–280g) were provided by the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The rats were anaesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 3% sodium pentobarbital (30–50mg/kg). The MAP was monitored by placing a catheter in separated right common carotid artery and measured by connecting a pressure transducer. Arterial blood was sampled by placing a catheter in the carotid artery. HSD and 0.9% NaCl solution (NS) were administrated by placing a catheter in the separated left jugular vein. A rat sepsis model was established using the CLP approach. We performed traditional disinfection of the abdomen and a median skin incision of approximately 2–3cm to expose the abdominal cavity. The cecum was freed from the mesentery; the base of the cecum was ligated with a 3-0 suture, and punctured at two sites 3mm apart by using a No. 9 needle. The intestinal canal was then restored to ensure smooth intestinal passage, the abdominal layers were sutured, the lost fluid was replenished, and the wounds were bandaged after disinfection with tamed iodine. Operation procedures for the sham operative (SOP) group were the same as-mentioned above, except for the CLP approach.

Rat groupsThe rats were randomly divided into four groups: the SOP group (n=21) received a subcutaneous injection of 30mL/kg 0.9% NaCl after the operation; the CLP group (n=45) received a subcutaneous injection of 30mL/kg 0.9% NaCl after the operation; the CLP+NS group (n=45) received a subcutaneous injection of 30mL/kg 0.9% NaCl and a jugular vein infusion of 5mL/kg 0.9% NaCl at 0.4mL/(kgmin) for 3h after the operation; and the CLP+HSD (n=28) group received subcutaneous injection of 30mL/kg 0.9% NaCl and a jugular vein infusion of 5mL/kg 7.5% NaCl/6% dextran at 0.4mL/(kgmin) for 3h after the operation.

The experiments were performed in adherence with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the treatment of animals and ethical animal research. In addition, animals were killed at 0, 9, and 18h after the operation. Blood samples and lung tissues were collected for examination. Equal volumes of 0.9% NaCl were immediately injected upon each blood sampling.

Determination of serum inflammatory cytokine levelsPlasma TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Blood samples were collected from the common carotid artery at 0, 9, and 18h after CLP. Blood aliquots of 0.8mL were added to Eppendorf tubes containing sterile pyrogen-free ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) anticoagulant and centrifuged (3000rpm) for 15min at 4°C. The plasma samples (100μL) obtained at 0, 9, and 18h after the operation were used, and the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were measured in duplicate using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Arterial blood gas analysisThe carotid artery blood of rats in each group was sampled (0.2mL) at 0, 9, and 18h after the operation, and the pH, PaO2, and PaCO2 in the blood samples were assayed using a portable blood gas analyzer (i-STAT, Abbott, Chicago, USA).

Percentage of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) neutrophilsBALF collection and cell sorting methods were performed as reported by Reis et al.7 and Callol et al.8 The trachea and lung of the sacrificed rats were exposed at 18h after the operation. The right bronchus was ligated, the trachea was fixed on the annular cartilage with forceps, and a transverse incision was made under it. By removing the No. 7 needle, an approximately 10-cm-long plastic infusion tube was kept remaining. The tube was inserted into the tracheal cavity, sutured at one end, and fixed on a 5-mL syringe at the other end. Sterile saline (2mL, 37°C) was slowly injected into the lung, and suctioned back after 30s. The above procedures were repeated thrice and a total of 5mL of BALF was collected. The BALF was centrifuged at 3000rpm for 10min and the cells in the pellet were stained using Wright's staining. One hundred cells were counted and classified under a microscope equipped with an oil-immersion lens according to leukocyte features. The percentage of neutrophils was calculated as follows: percentage of neutrophils (%)=number of neutrophils counted/number of total cells counted×100%.

Measurement of lung myeloperoxidase (MPO) activityAll the rats were sacrificed 18h after the operation. The frozen right lower lobe lung samples were then weighed and homogenized in 2mL of 50mmol/L phosphate buffer at pH 6.0 containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). The samples were then frozen on dry ice and thawed at room temperature thrice, after which they were sonicated. The suspensions were then centrifuged at 4000rpm for 15min. MPO activity in the supernatant was assessed by measuring the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-dependent oxidation of o-dianisidine dihydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co.), according to a previous report.9 We mixed 0.1mL of the supernatant with 2.9mL of phosphate buffer (50mmol/L, pH 6.0) containing 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) and 0.167mg/mL o-dianisidine dihydrochloride (Sigma). The change in absorbance was measured at 460nm using a spectrophotometer (U-2000; Hitachi Instruments, Webster, NY). MPO activity was derived from the observed change in absorbance per minute. The MPO activity was normalized further to the total protein content of the supernatant, which was measured by the micro-Lowry technique.10 Activity is expressed as units of MPO activity per milligram of protein.

Wet to dry weight ratio of lung issuesAfter the rats were sacrificed, the right lung tissues were harvested and the wet weight was measured first. Then, the tissue samples were dried at 80°C for 72h and weighed again to obtain the dry weight. The ratio of wet to dry weight was calculated.

Pathological changes in the lung tissueThe lung tissues were harvested at 18h for histopathological analyses. The harvested lung tissues were fixed in buffered formaldehyde (10% in PBS, pH 7.4) for 8h. The fixed organs were dehydrated in graded ethanol and embedded in paraffin (Tissue-processor, Japan). Then, 4-μm sections were cut using a sliding microtome (Leica Jung SM 2000, Germany) and the paraffin was removed using xylene. The tissue sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin and visualized under a light microscope.

Determination of the ICAM-1 mRNA level in lung tissuesThe rats were sacrificed at 9 and 18h after the operation. Total RNA was extracted using the one-step approach by adding 1mL Trizol to 100mg of right lung tissue. cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer's instructions, and 1μL cDNA was used as the template for PCR amplification using the following primer sequences: upstream: 5′-CGGTAGACACAAGCAAGAGA-3′; downstream: 5′-GCAGGGATTGACCATAATT-3′; β-actin (207bp) upstream: 5′-CCAACTGGGACGATATGGAG-3′; downstream: 5′-CAGAGGCATA CAGGGACAAC-3′. The PCR reaction conditions were as follows: predenaturation at 94°C for 5min until start of the cycle; followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 56°C for 30s, and 72°C for 1min; and a final extension step at 72°C for 7min. For β-actin amplification, the following conditions were used: predenaturation at 94°C for 5min until start of the cycle; followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 56°C for 30s, 72°C for 1min; and a final extension step at 72°C for 7min. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the amplified products were scanned using a gel imaging system. The mRNA expression level was expressed as the ratio of ICAM-1 to β-actin band luminosity.

Survival rateThe survival rate of experimental animals in each group was given by point statistics at 9 and 18h postoperatively.

Statistical methodsMeasurement data were statistically processed using SPSS 11.5 software and expressed as means±standard deviation (x¯±s). Means among multiple groups were compared using ANOVA, two groups were compared using t-test, and p<0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

ResultsHemodynamic effects of HSDThe baseline MAP in each group was not significantly different (Table 1). During the entire research period, the MAP was stable in the SOP group, but decreased significantly between 9 and 18h in the CLP and CLP+NS groups. Hemodynamic disorders were detected but the MAP was significantly better in the CLP+HSD group than in the CLP and CLP+NS groups at 9h. The difference was statistically significant and the HSD showed a continued improvement in blood pressure from 9h onwards.

Baseline values of parameters in each group.

| SOP (n=10) | CLP (n=10) | CLP+NS (n=10) | CLP+HSD (n=10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP (mmHg) | 119±5 | 120±7 | 117±6 | 118±7 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 74.72±13.59 | 74.81±19.13 | 73.67±13.27 | 75.08±15.59 |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 56.55±12.46 | 60.91±10.41 | 58.13±12.35 | 59.18±11.24 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 90.14±11.80 | 88.63±12.76 | 87.26±13.56 | 89.23±10.84 |

| pH | 7.411±0.034 | 7.407±0.030 | 7.419±0.033 | 7.413±0.029 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 122±11 | 121±10 | 123±12 | 120±11 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 38±6 | 37±5 | 37±5 | 38±4 |

Baseline levels of mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), arterial blood pH, PaO2, and PaCO2 in rats that received laparotomy plus vehicle (SOP, n=10), cecal ligation and puncture (CLP; n=45), CLP plus normal saline (CLP+NS, jugular vein injection of 5mL/kg 0.9% NaCl at an infusion speed of 0.4mL/(kg·min) for 3h after the operation; n=45), and CLP plus HSD (CLP+HSD, jugular vein infusion of 5mL/kg 7.5% NaCl/6% dextran at an infusion speed of 0.4mL/(kg·min) for 3h after the operation; n=28). Data are expressed as means±SEM.

The baseline TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in each group were not significantly different (Table 1). The plasma TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in the SOP group were not significantly different at 9 and 18h, suggesting that the laparotomy did not significantly influence the expression of these markers. The plasma TNF-α levels in the CLP and CLP+NS groups were significantly increased at 9h and gradually increased thereafter. During the entire experiment phase, the plasma TNF-α level in the CLP+HSD group was significantly lower than the corresponding values in the CLP and CLP+NS groups (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, in the CLP and CLP+NS groups, the IL-1β expression levels increased sharply at 9h and 18h. The plasma IL-1β level in the CLP+HSD group showed biphasic changes and although it was significantly lower than that in the CLP, the IL-1β level in this group was significantly different from that in the SOP group at 9 and 18h (Fig. 1B). The plasma IL-6 levels in the CLP and the CLP+NS groups increased sharply until 9h and decreased slowly thereafter. The plasma IL-6 level in the CLP+HSD group was initially lower than that in the CLP and CLP+NS groups; however, the levels were similar among these groups at 18h (Fig. 1C).

Effect of HSD on (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-1β, (C) IL-6, (C) pH, (D) PaO2, and (E) PaCO2 in rats with sepsis induced by peritonitis. The graphs illustrate the changes during the experimental period in animals that received laparotomy plus vehicle (SOP; n=10), cecal ligation and puncture (CLP; n=45), CLP plus normal saline (CLP+NS, jugular vein injection of 5mL/kg 0.9% NaCl at an infusion speed of 0.4mL/(kgmin) for 3h after the operation; n=45), and CLP plus HSD (CLP+HSD, jugular vein infusion of 5mL/kg 7.5% NaCl/6% dextran at an infusion speed of 0.4mL/(kgmin) for 3h after the operation; n=28). Data are expressed as means±SEM. *p<0.05 for all groups vs. sham. #p<0.05 for HSD vs. NS.

The baseline levels of arterial blood pH, partial pressure of oxygen, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in each group were not significantly different (Table 1). The arterial blood pH in each group was decreased at 9h, but it further decreased at 18h in the CLP and CLP+NS groups, whereas the blood pH showed the same gradual increasing trend in the SOP and CLP+HSD groups (Fig. 1E).

The arterial partial pressure of oxygen did not significantly change in the SOP group, but it showed a sharp decrease at 9h followed by a gradual decrease until 18h in the CLP and CLP+NS groups. The arterial partial oxygen pressure in the CLP+HSD group decreased at 9h, but it was significantly higher than the corresponding values in the CLP and CLP+NS groups. Such effects continued until 18h (Fig. 1F).

The arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide increased slightly at 9h in the CLP, CLP+NS, and CLP+HSD groups, but showed a continuous rising trend even at 18h in the CLP and CLP+NS groups. The arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide in these two groups showed a higher increasing trend than that in the CLP+HSD group, which was slightly increased during the study duration but did not show significant change compared to the baseline value at 0h in the SOP group (Fig. 1G).

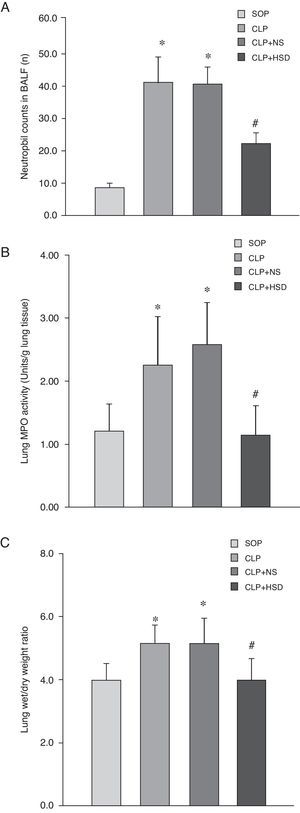

Effect of HSD on the number of BALF neutrophils, lung myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and wet to dry weight ratio of lung tissueThe percentage of BALF neutrophils was higher in the CLP and CLP+NS groups than in the SOP group. There were more BALF neutrophils in the CLP+HSD group than in the SOP group; however, this value was still significantly lower than the corresponding values in the CLP and CLP+NS groups (Fig. 2A). The MPO activities in the CLP and CLP+NS groups were significantly increased as compared to the SOP group; however, the MPO activity in the lung tissue in the CLP+HSD group was lower than that in the CLP and CLP+NS groups (Fig. 2B). The CLP and CLP+NS groups had a higher wet to dry weight ratio of lung tissues as compared to the SOP and CLP+HSD groups (Fig. 2C).

Effect of HSD on (A) BALF neutrophil number, (B) lung tissue MPO and (C) wet/dry weight ratio of lung tissue activities in rats with sepsis induced by peritonitis. The graph illustrates changes during the experimental period in animals that received laparotomy plus vehicle (SOP; n=6), cecal ligation and puncture (CLP; n=6), CLP plus NS (CLP+NS; n=6), and CLP plus HSD (CLP+HSD; n=6). Data are expressed as means±SEM. *p<0.05 for all groups vs. sham. #p<0.05 for HSD vs. NS.

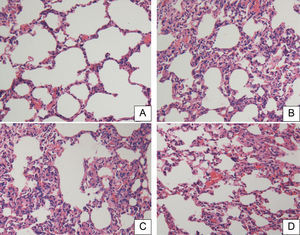

There were no significant pathological changes in rat lung tissue sections in the SOP group at 18h (Fig. 3A). The lung tissues in the CLP and CLP+NS groups showed significant inflammatory pathological changes such as hemorrhage, alveolar congestion, thickening of alveolar walls/hyaline membrane formations, and infiltration and aggregation of neutrophils in airspaces or vessel walls (Fig. 3B and C). The CLP+HSD group had significantly fewer inflammatory changes as compared to the CLP and CLP+NS groups (Fig. 3D).

Histopathological studies of lung tissue. Light microscopy showed lung sections of rats in the (A) sham-operated (SOP) group, (B) cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) group, (C) CLP+NS group, and (D) CLP+HSD group. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (original magnification, 200×).

The ICAM-1 levels in the CLP and CLP+NS groups were increased at 9h and further increased at 18h. The ICAM-1 levels in the CLP+HSD group were significantly lower than those in the CLP and CLP+NS groups (Fig. 4).

Effect of HSD on survival ratesThe rats in the SOP group did not die within 18h. The survival rates of animals in the CLP group at 9 and 18h were 62.2% and 31.1%, respectively. The survival rates of rats in the CLP+NS group at 9 and 18h were 57.8% and 35.6%, respectively. The survival rates of the CLP+HSD group at 9 and 18h were 85.7% and 64.3%, respectively. Thus, intravenous infusion of HSD can improve the early survival rate (within 18h) in CLP rats. However, the survival rate of the CLP+HSD group was decreased at 9h. Therefore, additional therapeutic means must be implemented in order to improve the survival rate of CLP rats using HSD.

DiscussionClinically, many cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor, interleukins, and adhesion molecules, are produced during sepsis as a result of stimuli by bacteria and bacterial endotoxins. Interactions between these various cytokines result in the activation of a cascade reaction.11 The septic shock progresses and patients frequently die from multiple organ failures because of inflammatory reaction imbalance, inflammatory cell infiltration, micro-thrombosis, microcirculation disorders, tissue hypoperfusion, lactic acidosis, imbalance between oxygen supply and demand, and decline of myocardial contraction force.

In a rat model with CLP-induced septic shock, bacteria leaked to the internal organs, infected the abdominal cavity, and caused systemic infection and septic shock. In the present study, the rats that underwent CLP exhibited signs such as piloerection, curling, fatigue, and hypokinesia, eating less, weight loss, shortness of breath, severe bleeding in snouts and inner canthi, and trembling. Rats in the SOP group moved freely, responded sensitively, and exhibited normal drinking behavior. The hemodynamic changes, times, and patterns of changes in the cytokine levels in the CLP group were similar to those observed in clinical human patients with sepsis while lung edema, congestion, and infiltrative inflammatory changes occurred in the lung tissues of rats. These symptoms are similar to those observed in human patients with sepsis. These results demonstrated that a septic shock rat model can be effectively established using the CLP approach.

The present study found that the CLP+HSD group showed significant hemodynamic improvement. This is supposed to be related to blood volume expansion owing to transfer of interstitial fluid and intracellular fluid into blood vessels by osmotic pressure gradients after injection of HSD into the blood vessels.12 The hypertonic saline can enhance myocardial contraction forces, improve cardiac capacity, and regulate angiostasis under the body's infectious state, thus helping improve the circulatory failure in sepsis.

In sepsis, multiple inflammatory pathways such as the cytokine network and coagulation cascade are triggered as a result of the complex interactions between the body and infectious factors such as bacteria.13 TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are released in massive amounts and inappropriate immune activation is induced in the body, resulting in organ- and cellular-level injuries. Fiorentino et al.14 found that appropriate expression levels of inflammatory cytokines are beneficial for a body's resistance to infection. Our study also verified that the TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in CLP+HSD rats were significantly decreased as compared to the CLP and CLP+NS groups. Furthermore, we observed that HSD did not completely inhibit these cytokines; rather, their expression levels were considerably reduced. This finding suggested that HSD plays a positive immunoregulatory role in the treatment of sepsis. We inferred that HSD can play this role via multiple pathways: during severe infections; immunoparalysis caused by the presence of immunosuppressive mediators such as PGE2, TGF-β, and IL-10; late MODS; inhibition of T cell proliferation by PGE2. In such cases, the injected hypertonic saline may help to improve the inhibition of T cell activation and proliferation by expressing additional levels of migration inhibitory factor.

In sepsis, proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1 activate endothelial cells and upregulate ICAM-1 expression. ICAM-1 is attached to the pulmonary capillary endothelium. Neutrophils adhere to the endothelial cells and become trapped in lung tissues continuously under the effects of β2-integrins and ICAM-1, and the lung is injured by the release of reduced oxygen-free radicals and proteases.15 Fahrner et al.16 observed that HSD can reduce the number of white blood cells increased by formyl-methionyleucylphenylalanine (FMLP) stimulus, cause respiratory bursts and polymorphonuclear cell aggregation, and increase the expression level of β2-integrin (CD18) in the normal human body. We also observed that HSD plays a positive regulatory role on the expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6; the ICAM-1 mRNA levels in lung tissues were lower in the CLP+HSD group than in the other two CLP groups. Furthermore, the various indicators were significantly better in the CLP+HSD group than in the CLP and CLP+NS groups. Taken together, these results suggest the protective role of HSD in acute lung injury caused after CLP.

ConclusionIn the present study, we created rat models of septic shock using the CLP approach. Rats that were intravenously injected with 7.5% NaCl/6% dextran (HSD) showed improvements in the circulatory failure during the study period after CLP. Our study also confirmed that the TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression levels and the ICAM-1 levels were lower in the HSD-treated rats than in the control rats. We inferred that HSD plays a positive immunoregulatory role in sepsis, thus inhibiting the overexpression of inflammatory response factors. Investigated parameters such as neutrophil percentage, MPO activity, wet to dry weight ratio of lung tissues, histopathological changes in the lung tissues, arterial blood gas indicators such as pH and partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide were significantly better in the HSD-treated rats than in the other CLP groups. Taken together, these findings suggested that HSD plays a protective role in acute lung injury caused by CLP. Our study showed that the hypertonic/hyperoncotic solution has better therapeutic effect in the treatment of septic shock and sepsis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by a grant from the Wuhan Municipal Health Bureau Fund (grant number WX10C15).