Stewardship programs have been developed to optimize the use of antibiotics, but programs focusing on antifungal agents are less frequent.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the quality of antifungal prescriptions in a tertiary care hospital, and to test if a simple educational activity could improve the quality of prescriptions.

MethodsThe study comprised three phases: 1) Retrospective audit of all antifungal prescriptions in a 6-month period, applying a score based on six parameters: indication, drug, dosage, route of administration, microbiologic adequacy after results of cultures, switching to an oral agent, and duration of treatment; 2) Creation of text boxes in the electronic medical records with information about antifungal agents, shown during prescription; 3) Retrospective audit of all antifungal prescriptions in a 6-month period, applying the same 6-parameters score, and comparison between the two periods.

ResultsAmong 333 prescriptions, fluconazole was the most frequently (80.5%) prescribed agent. Hematology (26.7%), Infectious Diseases Department (22.8%), Internal Medicine (15.9%) and Intensive Care Unit (14.4%) were the units with most antifungal prescriptions. The median score for the 333 prescriptions was 8.0 (range 0 – 10), and 72.7% of prescriptions were considered inappropriate. The median and mean scores in the first and second audit were 8.0 and 6.9, and 8.0 and 7.9, respectively (p<0.001). All items that comprised the score improved from the first to the second audit. Likewise, there was a reduction of inappropriate prescriptions (80.2% in the first audit vs. 64.6% in the second audit, p=0.001).

ConclusionsA large proportion of inappropriate prescriptions was observed, which improved with the implementation of simple educational activities.

Invasive fungal disease (IFD) is a major complication in hospitalized patients, affecting different populations, including patients with cancer, rheumatic diseases, patients with AIDS, transplant recipients, and critically ill patients.1,2 As a consequence, the number of antifungal prescriptions has increased. One of the greatest challenges in the management of IFD is how to prevent the inadequate use antifungal agents, with an impact on patient care and hospital and health system expenditures. Accordingly, stewardship programs have been developed in order to guide clinicians on how to use antimicrobial agents in an efficient way.3 Most of the stewardship programs have focused on antibiotics, with less initiatives in IFD and use of antifungal agents.4-8 In this study we evaluated the quality of antifungal prescriptions in a tertiary care hospital and tested if a simple educational activity could improve the quality of prescriptions.

Patients and methodsThis was a quasi-experimental study conducted at Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho, a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital located in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This hospital has about 250 beds, distributed in different clinics including medical and surgical specialties, hematopoietic and solid organ transplantation, hematology, oncology, and intensive care unit (ICU). The hospital provides a Mycology Laboratory with expertise in the diagnosis of superficial and IFD. Patient care, including prescription of antifungal agents, is provided by medical doctors and residents. The study was approved by the institution's ethical committee.

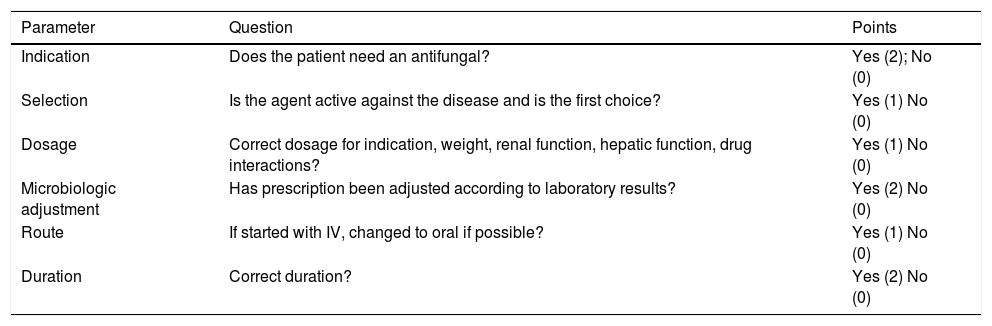

The study comprised three phases. In the first phase, we conducted a retrospective audit of all prescriptions of antifungal agents in a 6-month period (April through September 2016). The following antifungal agents were considered in the audit: fluconazole, amphotericin B (deoxycholate, lipid complex and liposomal), voriconazole, posaconazole, and echinocandins. Adequacy of antifungal prescriptions was defined according to the score proposed by Valerio et al,9 consisting of six items: indication, selection of the agent, dosage, microbiologic adjustment (appropriate change after results of cultures and other tests), administration route (change from parenteral to oral if possible) and duration. For each item a question was posed, and points were attributed accordingly (Table 1). The minimum and maximal points for each prescription were 0 and 10, respectively. Any prescription with a score below 10 was considered inadequate.

A scoring system for the evaluation of antifungal prescription adequacy.

IV = intravenous

For each prescription we collected data about the hospital ward and indication: prophylaxis, empiric or targeted treatment (when an antifungal agent was started once a fungal disease was diagnosed), by reviewing the patients’ charts. Cases in which an antifungal agent was started upon a suspicion of a fungal disease (e.g., candidemia) but the diagnosis was not confirmed were classified as “empiric”. The antifungal agent was deemed to have been used for “no apparent reason” when a clear reason for the use of antifungal was not fond after careful review of patients’ charts. Adequacy of each prescription was taken from the Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (aspergillosis and cryptococcosis),10,11 the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases (candidiasis),12 and the European Conference of Medical Mycology (mucormycosis, fusariosis).13,14

The following phase consisted of creation of charts with information about antifungal agents, including spectrum of activity, indication, dosages, cost, dose adjustments in case of liver or renal failure and drug interactions. The charts were inserted in the electronic medical records system in a way that whenever an antifungal drug was prescribed, the charts popped up as a new window that disappeared only after it had been scrolled from top to bottom, thus allowing the prescriber to read the information. All the hospital staff was informed about these changes before its implementation.

In the third phase we performed another retrospective audit in all antifungal prescriptions in a 6-month period (July through December 2018), using the same scoring system. The scores in the first and third phase were then compared.

Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, and compared between groups using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as medians and ranges or means and standard deviation, and compared using the Mann-Whitney test. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc).

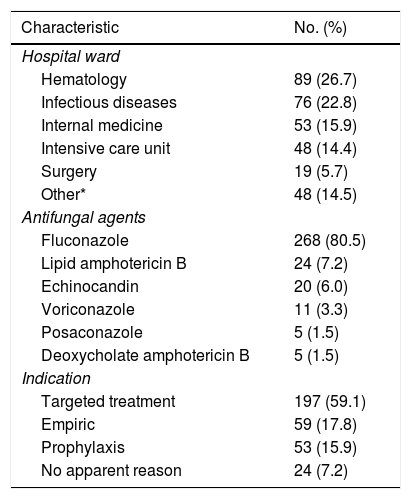

ResultsA total of 333 prescriptions of antifungal agents in 270 patients were audited: 172 in the first phase and 161 in the third phase of the study. The median age of the 270 patients was 51.5 years (range 17 – 89) and 130 patients (48.1%) were females. Most antifungal prescriptions originated from the Hematology ward (26.7%), followed by Infectious Diseases ward (22.8%), Internal Medicine (15.9%) and ICU (14.4%). Fluconazole was by far the most frequently prescribed agent (80.5%), followed by a lipid formulation of amphotericin B (7.2%), and an echinocandin (6.0%). The antifungal agents were given as prophylaxis in 15.9%, empiric in 17.7% and as targeted treatment in 59.2% (Table 2). Out of all fluconazole prescriptions, 65.3% were for targeted treatment, 15.3% as prophylaxis, 10.8% as empiric therapy, and 8.6% without an apparent reason. By contrast, the 24 prescriptions of a lipid formulation of amphotericin B were for empiric therapy (54.2%) or targeted treatment (45.8%)

Characteristics of 333 antifungal prescriptions.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Hospital ward | |

| Hematology | 89 (26.7) |

| Infectious diseases | 76 (22.8) |

| Internal medicine | 53 (15.9) |

| Intensive care unit | 48 (14.4) |

| Surgery | 19 (5.7) |

| Other* | 48 (14.5) |

| Antifungal agents | |

| Fluconazole | 268 (80.5) |

| Lipid amphotericin B | 24 (7.2) |

| Echinocandin | 20 (6.0) |

| Voriconazole | 11 (3.3) |

| Posaconazole | 5 (1.5) |

| Deoxycholate amphotericin B | 5 (1.5) |

| Indication | |

| Targeted treatment | 197 (59.1) |

| Empiric | 59 (17.8) |

| Prophylaxis | 53 (15.9) |

| No apparent reason | 24 (7.2) |

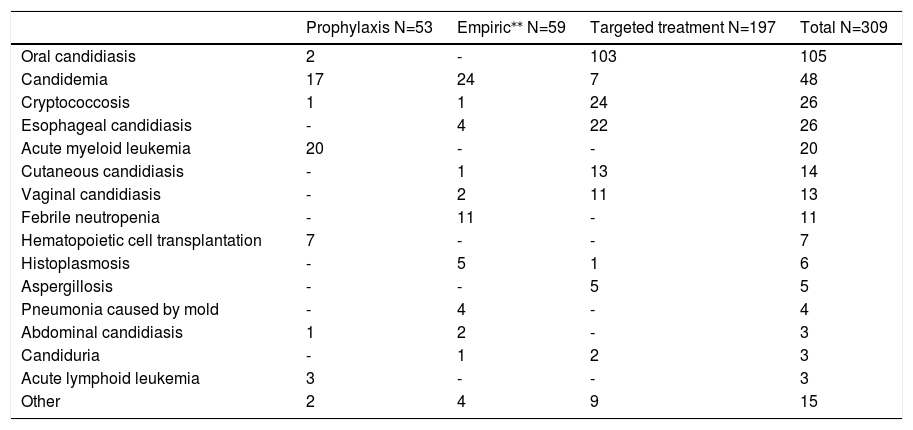

As shown in Table 3, among the 53 prescriptions as prophylaxis, the main indications were for acute myeloid leukemia in induction remission (n=20) and critically ill patients at high risk to develop candidemia (n=17). Among the 59 prescriptions as empiric therapy, candidemia (n=24) and febrile neutropenia (n=11) were the main indications. As targeted treatment (197 prescriptions), the main indications were oral candidiasis (n=103), cryptococcosis (n=24), esophageal candidiasis (n=22), cutaneous candidiasis (n=13), and vaginal candidiasis (n=11).

Indications for prophylactic, empiric and therapeutic use of antifungals in 309 prescriptions*.

| Prophylaxis N=53 | Empiric⁎⁎ N=59 | Targeted treatment N=197 | Total N=309 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral candidiasis | 2 | - | 103 | 105 |

| Candidemia | 17 | 24 | 7 | 48 |

| Cryptococcosis | 1 | 1 | 24 | 26 |

| Esophageal candidiasis | - | 4 | 22 | 26 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 20 | - | - | 20 |

| Cutaneous candidiasis | - | 1 | 13 | 14 |

| Vaginal candidiasis | - | 2 | 11 | 13 |

| Febrile neutropenia | - | 11 | - | 11 |

| Hematopoietic cell transplantation | 7 | - | - | 7 |

| Histoplasmosis | - | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Aspergillosis | - | - | 5 | 5 |

| Pneumonia caused by mold | - | 4 | - | 4 |

| Abdominal candidiasis | 1 | 2 | - | 3 |

| Candiduria | - | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 3 | - | - | 3 |

| Other | 2 | 4 | 9 | 15 |

The median score for the 333 prescriptions was 8.0 (range 0 – 10), and 72.7% of prescriptions were considered inadeqate. The item with the highest rate of inadequacy was microbiologic adjustment (57.7%), followed by duration of treatment (27.3%) and administration route (26.7%). The item with the lowest rate of inadequate prescriptions was indication (10.2%).

Comparing the two periods of audit, there were no significant differences (p=0.10) in the reasons for antifungal use, either in prophylaxis (15.1% vs. 16.8%), empiric (20.3% vs. 14.9%), or targeted treatment (54.7% vs. 64.0%). The rate of prescriptions without apparent reason reduced from 9.9% to 4.3% (p=0.06).

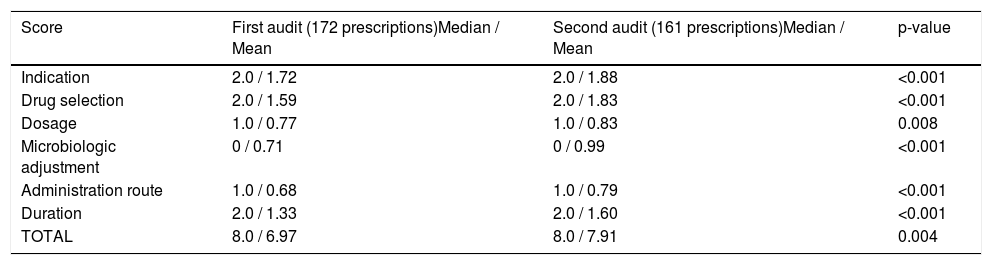

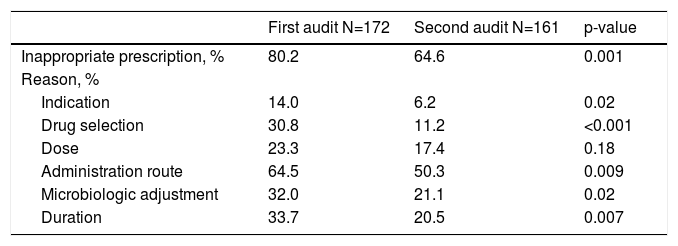

Table 4 shows the median and mean scores in the two periods of audit. The median and mean scores in the first and second audit were 8.0 and 6.9, and 8.0 and 7.9, respectively (p<0.001). All items that comprised the score improved from the first to the second audit. Likewise, there was a reduction of inadequate prescriptions (80.2% in the first audit vs. 64.6% in the second audit, p=0.001). The only item that did not show a significant improvement was the dosage (Table 5).

Median and mean scores of antifungal prescriptions in the two audit periods.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study attempting to characterize the quality of antifungal prescriptions conducted in Brazil. We found a high proportion of inadequate antifungal prescriptions, probably reflecting the lack of information about medical mycology and antifungal agents by prescribers. We also found that a simple measure, the creation of informative charts in the electronic medical record system, was able to improve the quality of antifungal prescriptions.

The audit of antifungal prescriptions allowed us to identify the most frequent antifungal agents used, their indications, and the wards with most of the prescriptions. Fluconazole was by far the most frequently prescribed agent, mostly for the treatment of oral candidiasis. In addition, 46 prescriptions were for cutaneous or mucosal candidiasis (Table 3). Other than superficial or mucosal fungal disease, candidemia was the most frequent clinical situation where an antifungal agent was prescribed, being 7 as targeted treatment and 41 (12.3% of all prescriptions) as empiric therapy or prophylaxis. Prophylaxis or empiric therapy for candidemia is appealing in ICU patients, despite the lack of solid evidences supporting these indications.15,16 Therefore, most ICU patients with clinical deterioration despite adequate antibiotic therapy receive empiric therapy for candidemia. A major problem in this scenario is when empiric therapy should be discontinued because the overuse of azoles or echinocandins may increase antifungal resistance.17 The use of fungal biomarkers such as 1,3-beta-D-glucan may help to discontinue empiric antifungal therapy in ICU patients.18,19

A preemptive (or diagnostic-driven) strategy for antifungal use in hematologic patients has been increasingly employed worldwide, after the incorporation of serum galactomannan.20 Although we did not include this category in our study, we have used preemptive antifungal therapy in the hematology ward since 2008. Indeed, three of the 11 prescriptions classified as “empiric” were preemptive.

In the present study we applied a scoring system developed by a Spanish group.9 In that study, antifungal prescriptions were evaluated in 100 patients, and the mean score of adequacy was 7.7, which is not different from our median score (8.0). The proportion of prescriptions with at least one inadequate item was 57% in the Spanish study, and the items with the highest rates of inadequacy were microbiologic adjustment (35%), drug selection (31%) and duration (27%). In the present study we found a higher rate of inadequate prescriptions (72.7%) and microbiologic adjustment (57.7%), duration (27.3%) and administration route (26.7%) were the items with the highest rate of inadequacy. These differences may be related to the characteristics of the hospitals or educational level of prescribers. With this regard, strategies to stimulate prescribers to collect microbiologic material to confirm diagnosis may improve the quality of the prescriptions.

A remarkable finding of our study was that the quality of prescriptions improved from the first to the second audit, with the proportion of inadequate prescriptions dropping from 80.2% to 64.6%, with significant improvement in all items except dosage of antifungal. Between the two audits we inserted informative charts in the electronic medical record system of the hospital, allowing clinicians to improve their education about the use of antifungal agents. Although we did not evaluate directly the level of knowledge of the prescribers, it is reasonable to assume that this simple educational activity resulted in significant improvement in the quality of prescriptions. Educational activities represent an important element for the success of antifungal stewardship programs, as shown in other studies.21-29 These activities include the application of questionnaires to evaluate gaps in knowledge of prescribers, the implementation of local guidelines, daily audits of antifungal prescriptions with bedside advice and others.

A potential limitation of our study was the long time between the first and second audits, due to a delay in the incorporation of educational alerts in the electronic medical records. This long time between audits could have influenced the results because of the turnover of medical residents that occur every year. Other limitation of our study is that we did not directly evaluate differences in the knowledge of prescribers before and after the implementation of the educational part of the study.

In conclusion, in this study we found a large proportion inadequate antifungal prescription, which was improved with the implementation of simple educational activities.