We report a case of Ralstonia pickettii sepsis in a 75-year old female patient with chronic kidney failure undergoing hemodialysis. The patient had a permanent vascular access for hemodialysis and was febrile for a few days prior to the sampling for microbiological analysis. She had a fever of 38.8°C, as well as a highly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (64mm/h), high C-reactive protein (290mg/L), and high white blood cell count (18,000 cells/μL). The antimicrobial therapy, which consisted of intravenous ceftriaxone 1g/d, was initiated two days before taking the samples.

The patient's blood culture was positive after 24h incubation in the BACTEC 9050 system. Typical pinpoint colonies were seen on blood agar and small lactose-negative colonies on McConkey agar. The oxidase test was positive. Gram staining revealed Gram-negative rods. Bacterial identification was done by the BBL Enteric/Nonfermenter ID System (Becton Dickinson). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the Etest (LIOFILCHEM) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2010 recommendations.

The isolate showed a high-level resistance to clinically useful aminoglycosides (amikacin, gentamicin, and tobramycin – MICs>256μg/mL). The strain was susceptible to the following antimicrobials: piperacillin/tazobactam (0.5μg/mL), ceftriaxone (3.0μg/mL), ceftazidime (2.0μg/mL), cefepime (1.5μg/mL), imipenem (0.25μg/mL), meropenem (0.5μg/mL), ciprofloxacin (0.064μg/mL), levofloxacin (0.064μg/mL), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (0.25μg/mL).

Despite the in vitro evidence of susceptibility to ceftriaxone, there was no clinical benefit from the administered treatment, as already described.1 The discrepancy between the in vitro testing and the in vivo activity of the drug required a switch to intravenous levofloxacin with a starting dose of 750mg and then 500mg, four times a day. Clinical symptoms subsided within 36hours.

To find the molecular basis of the observed high-level resistance to aminoglycosides, we assayed for putative 16S rRNA methylase genes. The armA, rmtA, rmtB, rmtC and rmtD genes were detected by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as previously described.2 No 16S rRNA methylase gene was identified in the isolate. Enzymatic modification is the other possible mechanism of high-level aminoglycoside resistance. The genes encoding for aminoglycoside modifying enzymes (AMEs) are usually found on plasmids and transposons. Most enzyme-mediated aminoglycoside resistance in Gram-negative bacilli is due to multiple genes. Further studies on AMEs are needed.

In an attempt to determine the source of R. pickettii sepsis, an assessment of the microbiological purity of the hemodialysis fluid was carried out. A sample of dialysis fluid was taken from the septum port in the line between the machine and the dialyser while simultaneously drawing a blood sample. This sample was inoculated into a tube of Trypticase soy broth (Beckton Dickinson) for 24hours at 35°C. Subcultures on blood agar and McConkey agar media were made. R. pickettii was again isolated.

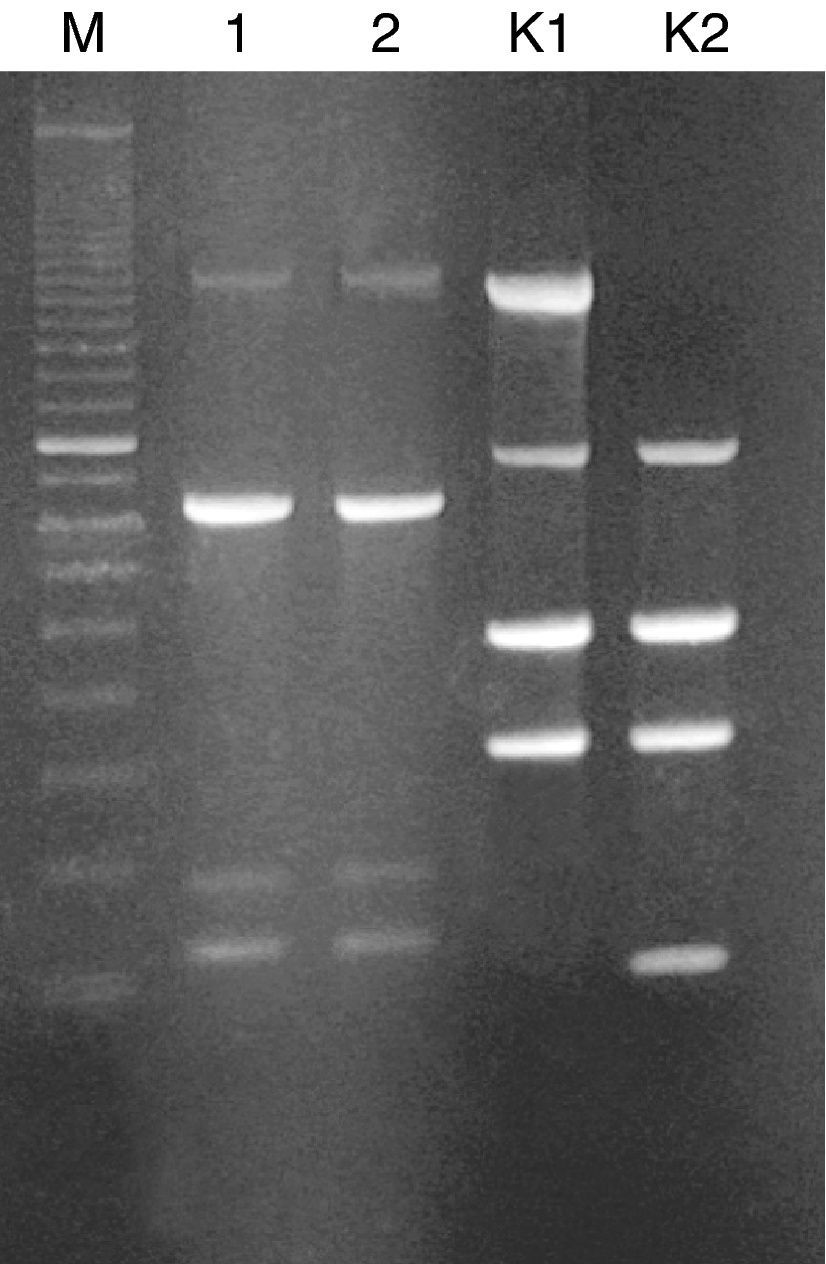

The dialysis fluid strain was compared to that isolated from patient's blood by using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) typing. RAPD was performed with Ready-To-Go RAPD Analysis Beads (GE Healthcare) as previously described.3 Two R. pickettii strain DNAs revealed identical RAPD profiles, each consisting of four bands (with size ranging from 220 to 1600bp) (Fig. 1). Thus, we successfully identified the hemodialysis system as a source of infection in our patient.

Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) of R. pickettii isolates generated with RAPD-4 primer (5′-AAGAGCCCGT-3′). Lanes: M, standard size marker (100-bp ladder); 1, R. pickettii isolate from the patient's blood; 2, R. pickettii isolate from the hemodialysis fluid; K1, RAPD profile of the reference strain E. coli C1a generated with RAPD-2 primer; K2, RAPD profile of the reference strain E. coli BL21 (DE3) generated with RAPD-2 primer (5′-GTTTCGCTCC-3′).

R. pickettii is a relevantly rare isolate that represents a potential threat for immunocompromised individuals, i.e. cancer patients, patients with hematological malignancies, or infants.4–6 It could also contaminate permanent indwelling intravenous devices, respiratory care solutions, distilled water, water for injection, or hemodialysis systems.7–9In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first case of R. pickettii sepsis described in Bulgaria. The hemodialysis system was identified as a source of R. pickettii infection. To prevent hemodialysis-related infections, it is important to maintain hemodialysis systems clear of microbial contamination.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare to have no conflict of interest.