Syphilis is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. Syphilis has three clinical stages and may present various oral manifestations, mainly at the secondary stage. The disease mimics other more common oral mucosa lesions, going undiagnosed and with no proper treatment. Despite the advancements in medicine toward prevention, diagnosis, and treatment syphilis remains a public health problem worldwide. In this sense, dental surgeons should be able to identify the most common manifestations of the disease in the oral cavity, pointing to the role of this professional in prevention and diagnosis. This study describes a case series of seven patients with secondary syphilis presenting different oral manifestations.

Humans are the only natural host known to date of syphilis, an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. This microorganism has positive tropism for several human organs and tissues, with complex clinical implications. Transmission occurs mainly through unprotected sexual intercourse and although the main inoculation site is the genital organs in general, extragenital areas such as the oral cavity and the anal region are also affected.1–5 Other important transmission pathways include the intra-uterus (transplacentary) route during labor,1,4 which causes congenital syphilis.

Syphilis has three clinical stages. The primary stage is characterized by a single chancre that manifests approximately 90 days after exposure and remits spontaneously within two to eight weeks. The secondary stage occurs between 2 and 12 weeks after exposure, when a rash develops on several parts of the skin. The rash subsides spontaneously with no treatment when the condition enters its latent stage. Also called late phase and rarely observed today, the tertiary stage is characterized by gummata and/or neurosyphilis that emerge three years or later after exposure.1,3–10

Although oral manifestations of syphilis may be observed at the primary stage, they are more commonly detected at the secondary stage of the disease as multiple painless aphthous ulcers or irregularly shaped lesions with whitish edges distributed on the oral mucosa and oropharynx, especially on the tongue, lips, and jugal mucosa.4,6,9 The appearance of such lesions varies widely, thus increasing the diagnostic complexity when the dental surgeon is not properly qualified to detect stomatological conditions. For this reason, oral manifestations of syphilis may be mistaken for other, more common oral conditions, with no early diagnosis or appropriate treatment.

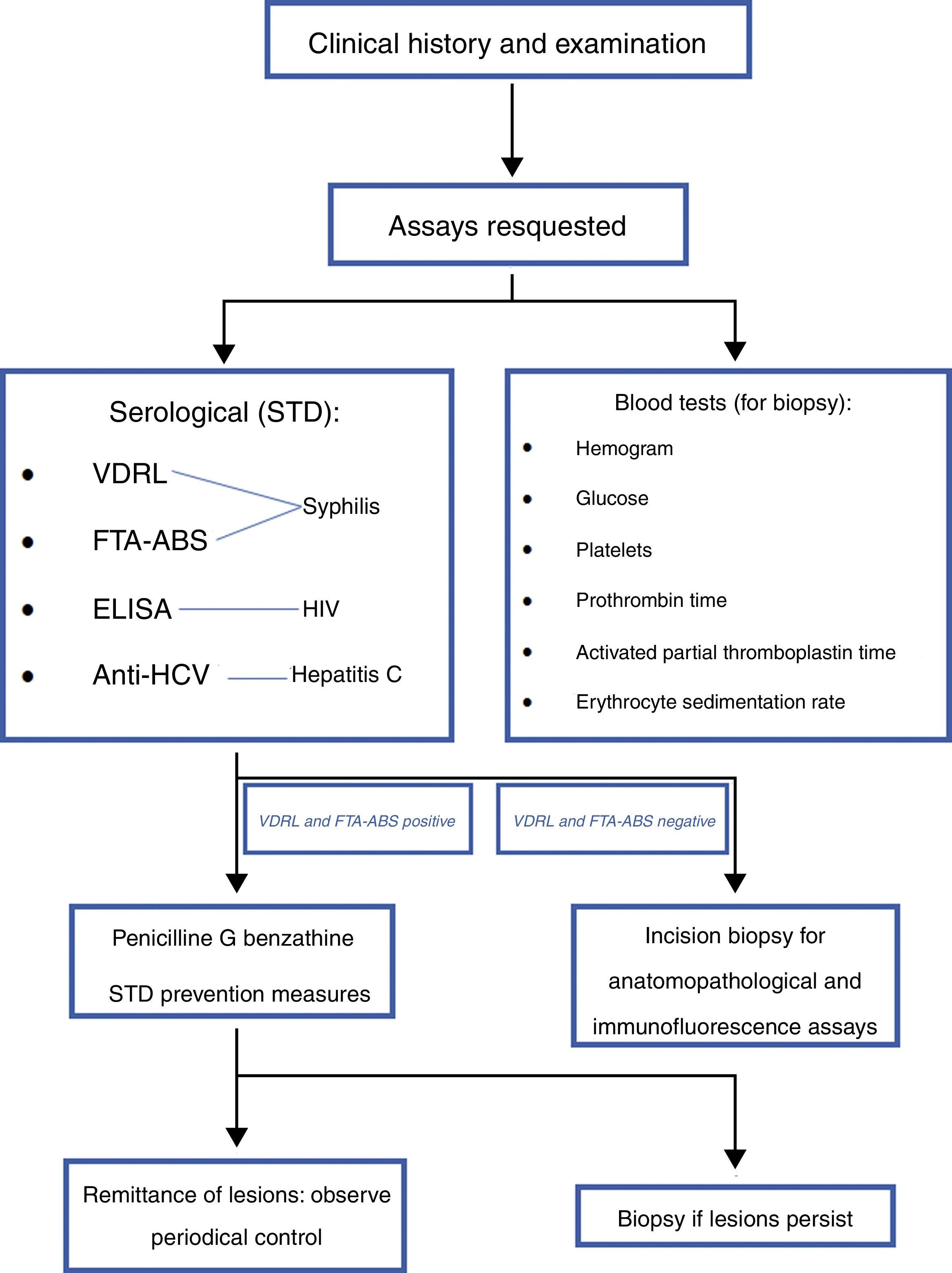

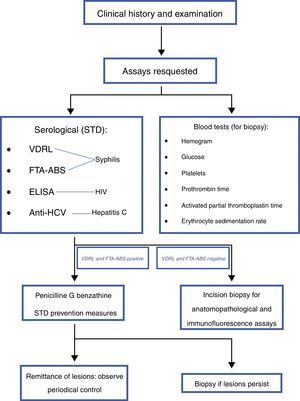

In addition to information obtained directly from the patient during consultation, the diagnosis of syphilis normally includes clinical examination and serological and microbiological assays. As a rule, biopsy is only required when lesions do not subside completely. Standard laboratory assays used to diagnose syphilis at any stage include treponemal and non-treponemal serum tests.3,9

Based on penicillin, the first successful anti-syphilis treatment was documented in 1943. Since then, penicillin is the drug of choice to treat the disease, usually penicillin G benzathine or penicillin G procaine.1,6

This case series describes different oral manifestations of secondary syphilis in seven heterosexual patients. The objective was to discuss the diagnosis and treatment protocols adopted by the Stomatology Unit, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil and to characterize secondary syphilis lesions in the oral cavity and the respective clinical follow-up of patients toward cure.

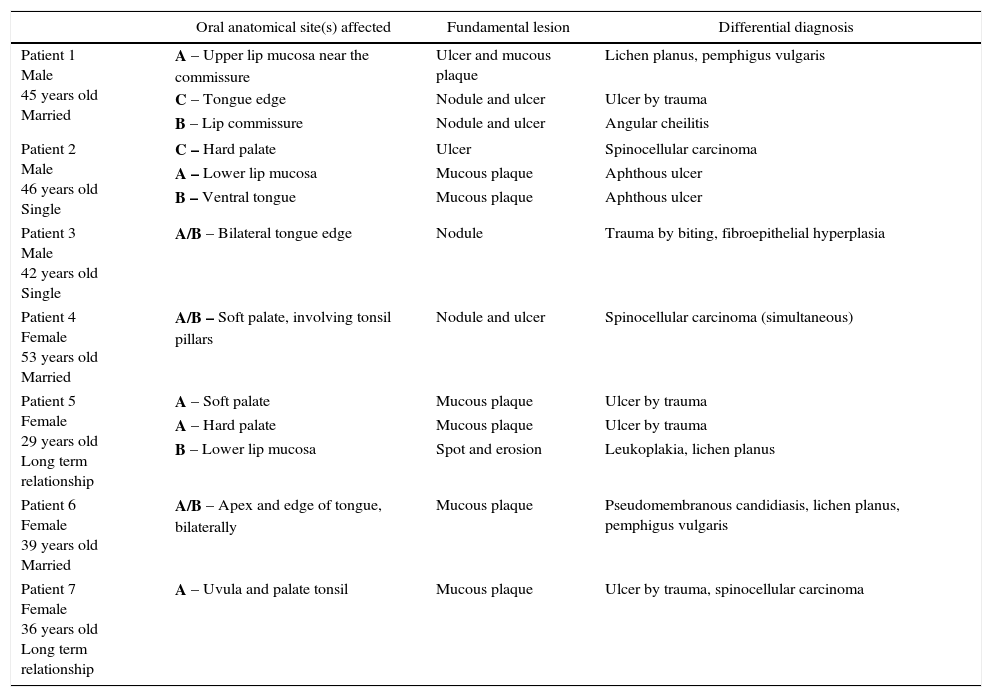

Clinical cases seriesHerein we present seven patients with oral manifestations of secondary syphilis that were referred to our Stomatology Unit. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the patients including age group, gender, and marital status.

Oral anatomical sites affected, type of fundamental lesion and differential diagnosis.

| Oral anatomical site(s) affected | Fundamental lesion | Differential diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 Male 45 years old Married | A – Upper lip mucosa near the commissure | Ulcer and mucous plaque | Lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris |

| C – Tongue edge | Nodule and ulcer | Ulcer by trauma | |

| B – Lip commissure | Nodule and ulcer | Angular cheilitis | |

| Patient 2 Male 46 years old Single | C – Hard palate | Ulcer | Spinocellular carcinoma |

| A – Lower lip mucosa | Mucous plaque | Aphthous ulcer | |

| B – Ventral tongue | Mucous plaque | Aphthous ulcer | |

| Patient 3 Male 42 years old Single | A/B – Bilateral tongue edge | Nodule | Trauma by biting, fibroepithelial hyperplasia |

| Patient 4 Female 53 years old Married | A/B – Soft palate, involving tonsil pillars | Nodule and ulcer | Spinocellular carcinoma (simultaneous) |

| Patient 5 Female 29 years old Long term relationship | A – Soft palate | Mucous plaque | Ulcer by trauma |

| A – Hard palate | Mucous plaque | Ulcer by trauma | |

| B – Lower lip mucosa | Spot and erosion | Leukoplakia, lichen planus | |

| Patient 6 Female 39 years old Married | A/B – Apex and edge of tongue, bilaterally | Mucous plaque | Pseudomembranous candidiasis, lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris |

| Patient 7 Female 36 years old Long term relationship | A – Uvula and palate tonsil | Mucous plaque | Ulcer by trauma, spinocellular carcinoma |

All patients were initially seen at primary healthcare centers complaining of multiple painful lesions in the mouth as their main health problem, and went through the same medical diagnostic protocol (Fig. 1). HIV and hepatitis C exams requested were negative for all patients, and none admitted drug addiction. The most common fundamental lesions were plaques on the mucosa, ulcers, nodules, spots, and erosion, in this order. The most affected anatomical sites included labial mucosa, tongue edge, hard and soft palates, lip commissure, ventral tongue, uvula, and tonsils, respectively. Fig. 2 shows photographs of the oral lesions of each patient. The most frequent diseases considered in the differential diagnosis were ulcers caused by trauma, spinocellular carcinoma, and autoimmune diseases. Table 1 lists the oral sites affected, the fundamental lesion type, and the differential diagnosis for each lesion.

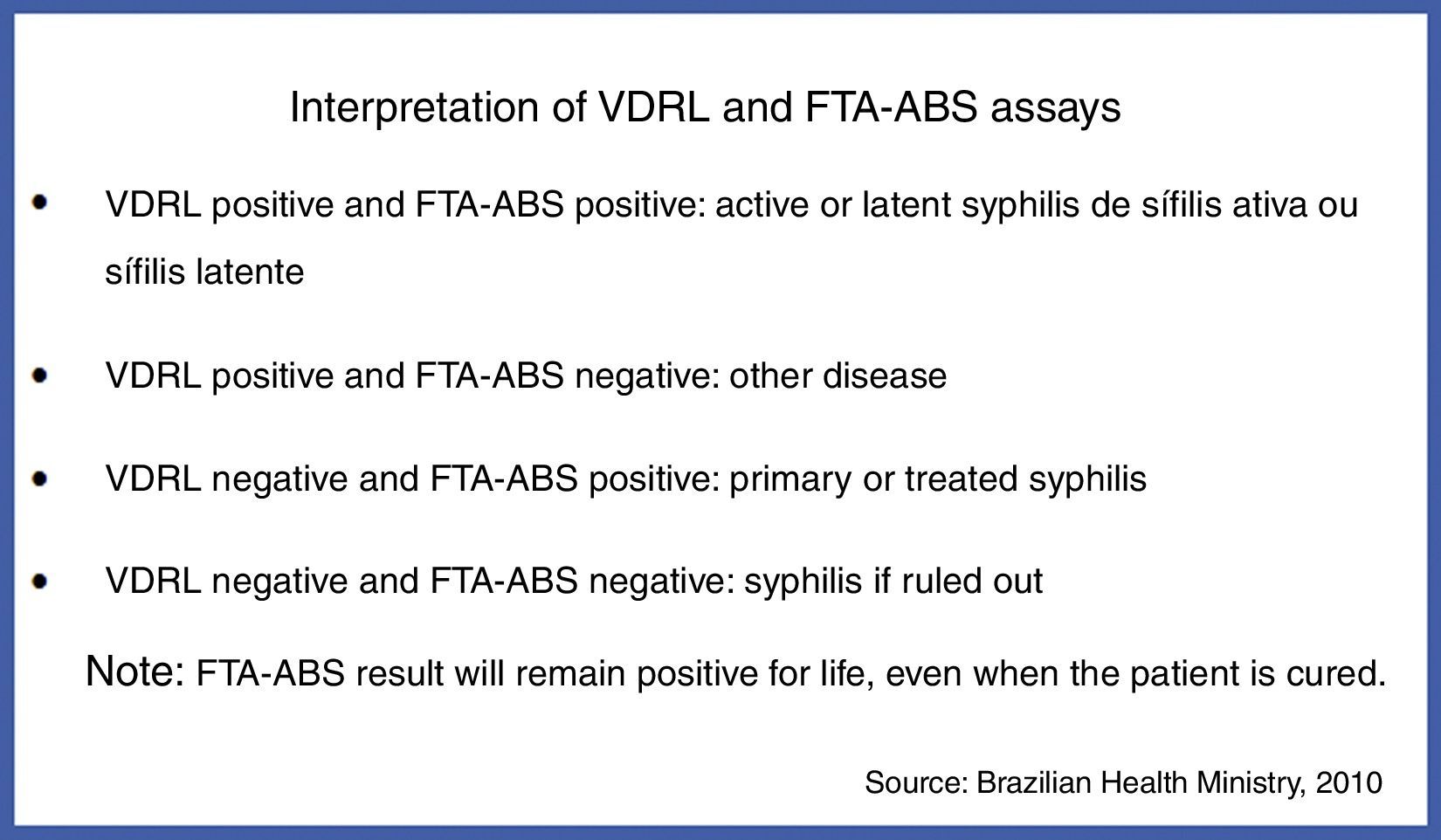

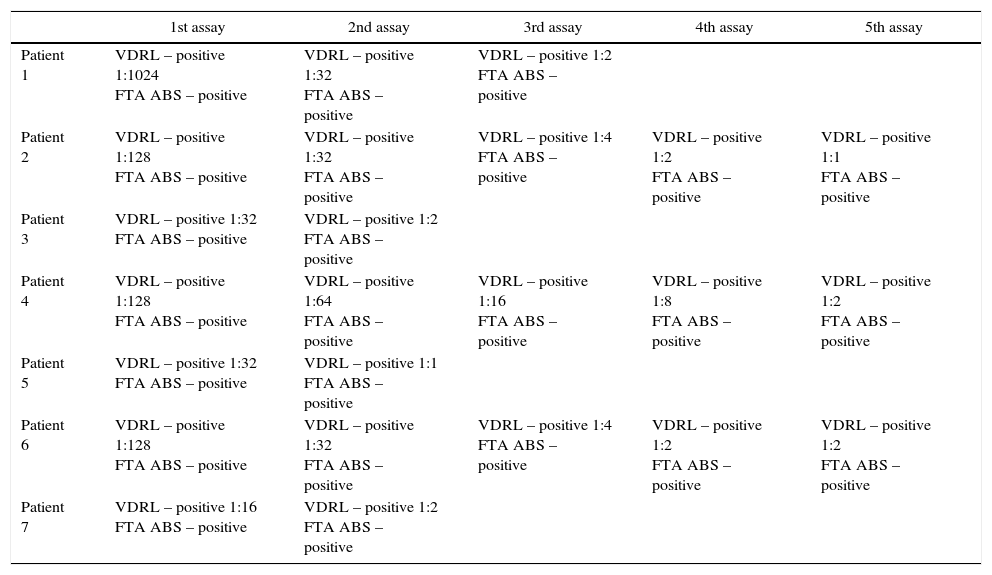

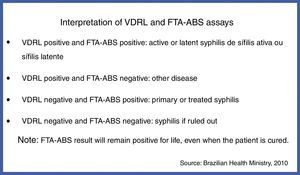

The venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test and the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test were carried out for all patients, which are conventionally requested to diagnose syphilis. Results of both tests are shown in Fig. 3,11 while serological assay results are shown in Table 2.

Results of serological assays. Assays were conducted at approximately 30-day intervals.

| 1st assay | 2nd assay | 3rd assay | 4th assay | 5th assay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | VDRL – positive 1:1024 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:32 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:2 FTA ABS – positive | ||

| Patient 2 | VDRL – positive 1:128 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:32 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:4 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:2 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:1 FTA ABS – positive |

| Patient 3 | VDRL – positive 1:32 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:2 FTA ABS – positive | |||

| Patient 4 | VDRL – positive 1:128 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:64 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:16 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:8 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:2 FTA ABS – positive |

| Patient 5 | VDRL – positive 1:32 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:1 FTA ABS – positive | |||

| Patient 6 | VDRL – positive 1:128 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:32 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:4 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:2 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:2 FTA ABS – positive |

| Patient 7 | VDRL – positive 1:16 FTA ABS – positive | VDRL – positive 1:2 FTA ABS – positive |

Upon confirmation of the diagnosis of syphilis, all patients received the conventional treatment as described by Brazilian health authorities.12 This treatment includes intramuscular injections of penicillin G benzathine 2,400,000 IU a week for three weeks, and follow-up with serological assays until VDRL titers are reduced. Patients are also instructed as to the importance of safe sexual practices, the risk of reinfection when sexual partners are not treated for the disease, and the risk of acquiring HIV and other STDs.

Oral manifestations of secondary syphilis disappeared completely within one to two weeks after the first penicillin injection avoiding the need to carry out biopsy.

DiscussionSTDs are among the main public health problems, causing increasing concern worldwide.13 Approximately 12,000,000 new cases worldwide are estimated to occur every year.14 Syphilis stands out as an important epidemiological marker in the investigation of other STDs, mainly HIV infection.15 In Brazil, an estimated 900,000 new cases are diagnosed every year.16

Two types of syphilis have been described. Congenital syphilis is vertically transmitted, while the acquired form of the disease is an STD.3,4 Acquired syphilis has three clearly distinct clinical stages, called primary, secondary, and tertiary. In addition, the literature mentions a latent stage, which comprises the timespan following infection with T. pallidum, characterized by sero-reactivity and no other evidence of the disease.1,4,5,7,8 All patients whose records were analyzed in the present study had been diagnosed with secondary syphilis, which is characterized by muco-cutaneous manifestations and by hematogenous dissemination that elicits the colonization of several organs.1,17 This stage starts within three to five months after infection. However, if not treated, secondary syphilis may recur as late as two years after exposure.18 It is accompanied by unspecific clinical signs and symptoms, such as general discomfort, headache, low-grade fever, anorexia, weight loss, and lymphadenopathy.4,9,17,18 Pharyngitis, myalgia, and arthralgia may also be present.9 These conditions disappear spontaneously, with no treatment, during the latent period.1,4,5,7,9

Oral manifestations of secondary syphilis include multiple, scattered lesions on the oral mucosa and oropharynx, though the tongue, lips, and jugal mucosa are the most commonly affected sites. Aphthous ulcers similar to gray plaques or ulcers with irregular, whitish edges that are painful at times are also observed. The diffuse character of the inflammatory process in the oropharynx may elicit complaints of sore throat.4,6,9 Oral lesions varies widely in appearance, increasing the complexity of diagnosis if the dental surgeon lack the required qualifications in stomatology. In contrast to primary syphilis, secondary syphilis in the oral cavity is not associated with oral sex habits.

The patients analyzed in the present study exhibited multiple lesions in the oral cavity caused by syphilis with the exception of patient 7, who exhibited a lesion in the uvula only. The lip mucosa and the tongue edge were the anatomical sites most frequently affected (in four patients each), followed by the hard and soft palates (in two patients each), ventral tongue, lip commissure, uvula, and tonsils (in one patient each). The fundamental lesions most commonly detected were mucous plaque (in seven anatomical sites), ulcer (in five), nodule (in four), spot and erosion (in one site each) (Table 1).

Clinical history, physical examination, and serological and microbiological assays are usually sufficient to diagnose syphilis. The information obtained in the present case series show that serological assays for syphilis should be requested from all suspected patients as a means to reach differential diagnosis. Therefore, depending on the clinical manifestation, differential diagnosis are trauma caused by bites, fibroepithelial hyperplasia, lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris, ulcer associated with trauma, angular cheilitis, spinocellular carcinoma, aphthous ulcers, and leukoplakia (Table 1). The variety of differential diagnosis in this case series confirms the findings described in previous studies, that is, secondary syphilis takes on several manifestations in the oral cavity, in which case the disease mimics other more frequent lesions in the oral mucosa, occasionally proceeding along its course with no proper diagnosis and treatment.1–4,8,9

The serology assays requested for the patients in the present study included VDRL and FTA-ABS to investigate syphilis, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for HIV and HCV. All patients had positive VDRL and FTA ABS results (Table 2), confirming the diagnosis of secondary syphilis. The results of HIV and HCV tests were all negative.

It has been shown that patients with syphilis are at higher risk of acquiring other STDs, especially HIV infection, since the syphilitic lesions are suitable sites for the virus to enter the human body.6 This highlights the importance of instructing patients as to preventive measures concerning safe sexual behavior, appropriate medical treatment of partners diagnosed positive for any relevant disease, and the awareness of the risks around sharing needles.

Treponemal and non-treponemal assays are the standard laboratory tests used to detect the presence of syphilis at any stage.3,9 Results of positive non-treponemal assays are reported as the lowest positive dilution. These assays are suitable for evaluating response to treatment and to assess the likelihood of reinfection. However, these tests are not indicated during the latent stage of the disease due to their poor sensitivity.18 These assays include the VDRL and its simplified version, the rapid plasma regain (RPR) test.3,9 Due to their increased specificity and sensitivity, the treponemal assays Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA), the FTA-ABS assay, and ELISA are used mainly as diagnosis confirmation tools.3,9 However, these tests do not clarify activity of the disease and, in most cases, will always remain positive, even after successful treatment.18

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of fast treponemal assays were shown to be comparable to those of standard methods.19 The authors concluded that when resources are limited (that is, when access to laboratories is difficult and screening for syphilis is not conducted), the fast detection assays are useful alternatives.

The first effort to treat syphilis was successfully conducted in 1943, using penicillin, which has since retained its status as drug of choice for treating of all stages of syphilis. Both penicillin G benzathine or penicillin G procaine are used for this purpose.1,6 The Brazilian Ministry of Health defines a single 2,400,000 IU intramuscular dose of penicillin G benzethine as the treatment of choice for both primary and secondary syphilis. However, the tertiary stage of the disease is treated with the same dose, repeated weekly for three weeks.5,12 Due to the difficulty to determine whether secondary syphilis in the cases evaluated was at the early or late stages, the treatment for late secondary syphilis was adopted in order to improve the chances of success.

For patients hypersensitive to penicillin, oral administration of doxycycline 100mg twice a day for 14 days or tetracycline 500mg four times a day for 14 days is indicated, with similar efficacy. These regimens are effective to treat primary, latent secondary, and early secondary stages of syphilis. Cases estimated to be in progress for one year or more (or when it is not possible to establish date of infection), treatment duration is increased to 28 days, either with doxycycline or tetracycline.1,5

Evidence indicates that azithromycin 1g a week for two to three weeks is effective to treat syphilis in penicillin-hypersensitive patients. However, the specialized literature warns that resistance to azithromycin has emerged quickly.9

Although the treatment protocols for syphilis have been clearly defined, few randomized clinical studies have been conducted to ascertain whether azithromycin or penicillin G are more effective to treat early syphilis. For each individual case, the decision to prescribe one or other of these drugs should be based on an evaluation of the cost–benefit relationship and on any risks the patient may have to face.3 A systematic review has recommended that azithromycin should be prescribed to treat early syphilis, though it has to be considered an alternative approach when the patient has hypersensitivity to penicillin or doxycycline is not a feasible option.20 The records of all patients analyzed in the present study show that none had such hypersensitivity.

ConclusionIn spite of the advances in medicine toward the prevention and early diagnosis and treatment of syphilis, the disease remains a public health problem worldwide. The growing prevalence of the disease in immunocompetent individuals is reason for concern, indicating poor compliance with safe sex practices to prevent STDs. Primary syphilis may be observed in the oral cavity, and has been associated with oral sex. The secondary stage of the disease takes a variety of oral manifestations, mimicking other more frequent lesions in the oral cavity, going by undetected and hence remaining without proper treatment. The analysis of a suspected patient's clinical history, combined with physical examination and serological assays normally affords a conclusive diagnosis of the disease, and biopsy is not normally required as an initial diagnostic resource. Therefore, the dental surgeon should be aware of the most common manifestations of syphilis in the oral mucosa so as to play a role not only in the treatment of syphilis, but also in the diagnosis of the disease.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.