The results of several new clinical trials that compared the effectiveness of entecavir (ETV) treatment with that of adefovir (ADV) treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) were published in recent years. However, the numbers of patients included in these clinical trials were too small to draw a clear conclusion as to whether ETV is more effective than ADV. Therefore, a new meta-analysis was needed to compare ETV with ADV for the treatment of CHB. A search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR), MEDLINE, the Science Citation Index, Embase, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and the Wanfang Database for relevant studies published between 1966 and 2010 was performed. Trials comparing the use of ETV and ADV for the treatment of CHB were assessed. Of the 2,358 studies screened, 13 randomized controlled clinical trials comprising 1,230 patients (ETV therapy, 621; ADV therapy, 609) were analyzed. The serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA clearance rate obtained in patients treated with ETV was significantly higher than that in patients treated with ADV at the 24th and 48th weeks of treatment (24 weeks: 59.6% vs. 31.8%, relative risk [RR], 1.82, 95% CI: 1.49–2.23; 48 weeks: 78.3% vs. 50.4%, RR, 1.61, 95% CI: 1.32–1.96). The serum HBeAg clearance rate, the HBeAg seroconversion rate, and the ALT normalization rate obtained for patients treated with ETV were also higher than the corresponding values for patients treated with ADV at the 48th week of treatment. The safety profiles were similar between patients treated with ETV and those treated with ADV. The evidence reviewed in this meta-analysis suggests that patients with hepatitis B have a greater likelihood of achieving a viral response and a biomedical response when treated with ETV than when treated with ADV.

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver and can cause both acute and chronic disease. Hepatitis B puts people at a high risk of death from liver cirrhosis and cancer. Approximately 2 billion people worldwide have been infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), and approximately 350 million live with chronic infection.1 In mainland China, a nationwide survey in 2006 showed that the prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was approximately 1.5% in children under the age of 8 years and 7.18% in the nationwide population between the ages of 1 and 59 years.2 HBV has become the most important cause of chronic hepatitis and end-stage liver disease in China.

Adefovir (ADV) and entecavir (ETV) are nucleos(t)ide analogs that have been approved for the treatment of chronic HBV infections for a number of years. ETV is associated with a delayed development of resistance and a low incidence of resistance in treatment-naïve patients. In addition, this drug exhibits antiviral activity against lamivudine (LAM)-resistant HBV, although ETV exhibits some degree of cross-resistance.3 In recent years, a number of clinical trials have compared the efficacy and adverse effects of ETV and ADV for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B (CHB).4–17 However, these clinical trials have reached inconsistent conclusions. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis that included a relatively large number of patients. The data for this meta-analysis were collected from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR), MEDLINE, the Science Citation Index (SCI), the Excerpta Medica Database (Embase), the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), the China Biological Medicine Database (CBM), and the Wanfang Database, and were used to compare the efficacy of ETV treatment with that of ADV treatment in patients with hepatitis B.

Materials and methodsSearch strategyThe CCTR, MEDLINE, the SCI, Embase, the CNKI, the CBM, and the Wanfang Database were searched to identify randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) published in the area of hepatitis B and antiviral therapy between 1966 and 2010. The keywords used in the literature searches were hepatitis B, HBV, entecavir, adefovir, treatment, and trial.

Data extractionTwo authors (Liu E and Zhao S) independently screened titles and abstracts for potential eligibility and reviewed the full texts to determine final eligibility. The data were independently extracted from the included trials for quantitative analyses, and any disagreement was subsequently resolved by discussion. The quantitative data included sample size; pre-treatment patient characteristics, including the age range and gender; type of treatment (ADV or ETV); doses of the drugs; SVRs; HBeAg seroconversion rate; and viral suppression at the end of treatment.

Inclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria applied were the following: (i) study design–the RCT was performed to compare the therapeutic effects of ADV and ETV; (ii) study duration–patients were treated for 24 or 48 weeks; (iii) language of publication–English or Chinese; (iv) outcomes measured–HBeAg seroconversion rate, serum HBeAg clearance rate, serum HBV DNA clearance rate, and ALT normalization rate. Reports that concerned the same studies were excluded by examining the author list, institution, sample size, and results.

Outcome measureThe HBeAg seroconversion rate, the serum HBeAg clearance rate, the serum HBV DNA clearance rate and the ALT normalization rate were used as the main outcome measures to assess the effects of ADV or ETV treatment in the included trials. Serum HBeAg clearance or HBV DNA clearance was defined as a reduction in HBeAg or HBV DNA to undetectable levels. All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat method.

Assessment of study qualityTwo authors (WeiK and Li Y) independently and informally assessed the study quality by treatment type (ADV or ETV); doses; rates of response; study population, eligibility criteria and participation rate; reasons for failure to complete the study; covariates and cofounders with appropriate techniques for control; acknowledgement of commercial support; and statistical methodology.

Statistical analysisIn this meta-analysis, a random- or fixed-effects model was adopted because of the anticipated variability among trials with respect to the patient populations.18,19 Meta-analysis was performed using fixed-effects or random-effects model, depending on the absence or presence of significant heterogeneity. When heterogeneity due to variability was significant (p>0.1), a random-effects model was used; otherwise the fixed-effects model was used. The measure of association used in this meta-analysis was the relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The summary RR with the 95% CI was calculated using RevMan 5.0 with the random- or fixed-effects model (Review Manager Version 5.0 for Windows; The Cochrane Collaboration–Oxford, UK). The result was assumed to be statistically significant when the 95% CI did not include one.

Heterogeneity was assessed using a chi-square test, and the quantity of heterogeneity was measured using the I2 statistic. When patients were discontinued, the data were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Patients who did not achieve the selected endpoints were considered to have failed therapy. The total number of patients was used as the denominator.

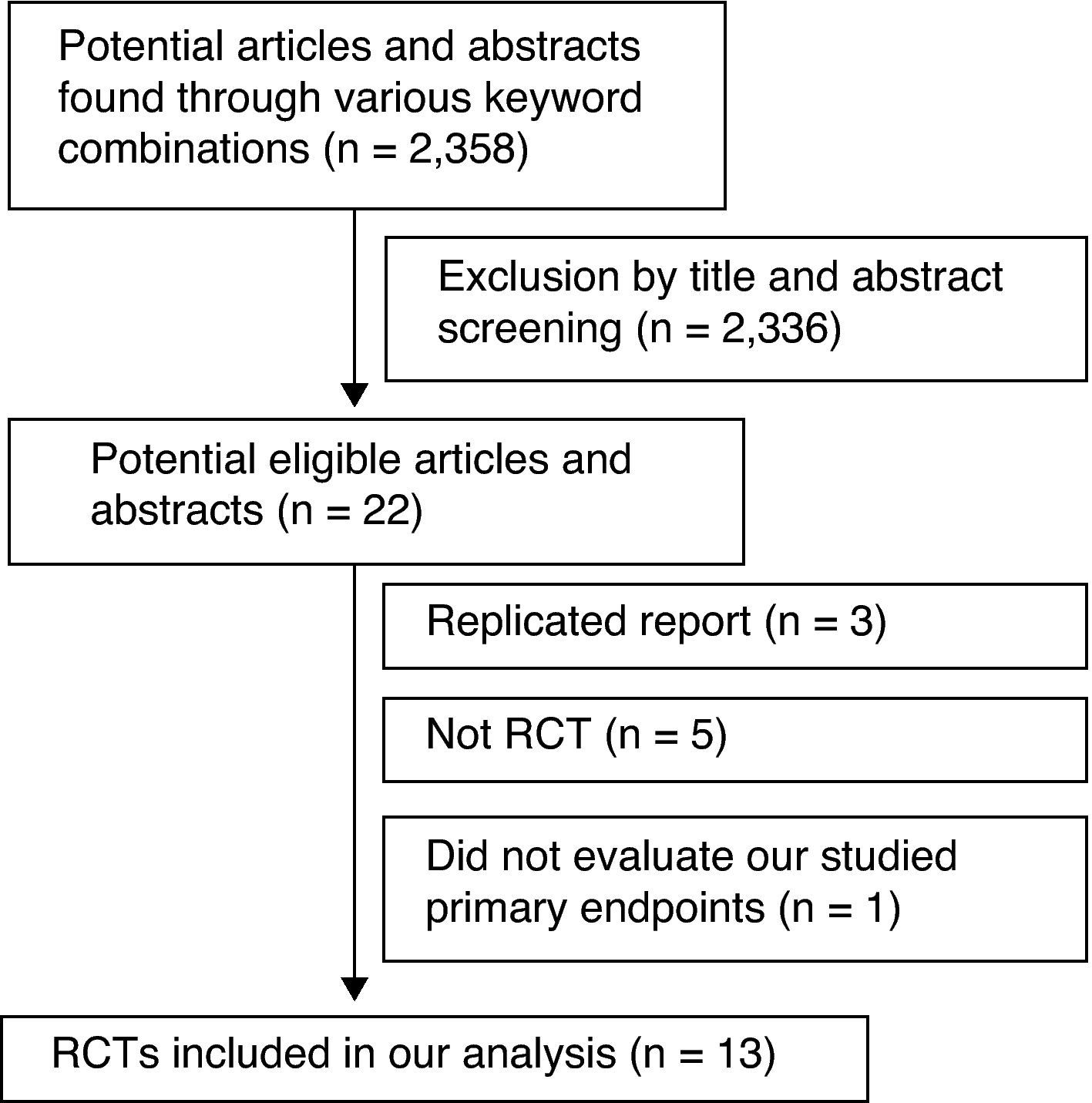

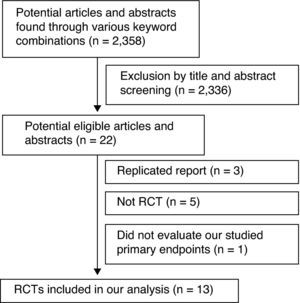

ResultsLiterature researchOf the 2,358 articles identified through the electronic database search, 13 RCTs matched the selection criteria. 4–17 There was unanimity between the two authors regarding the selection of relevant articles (Sihai Zhao and Enqi Liu) (Fig. 1).

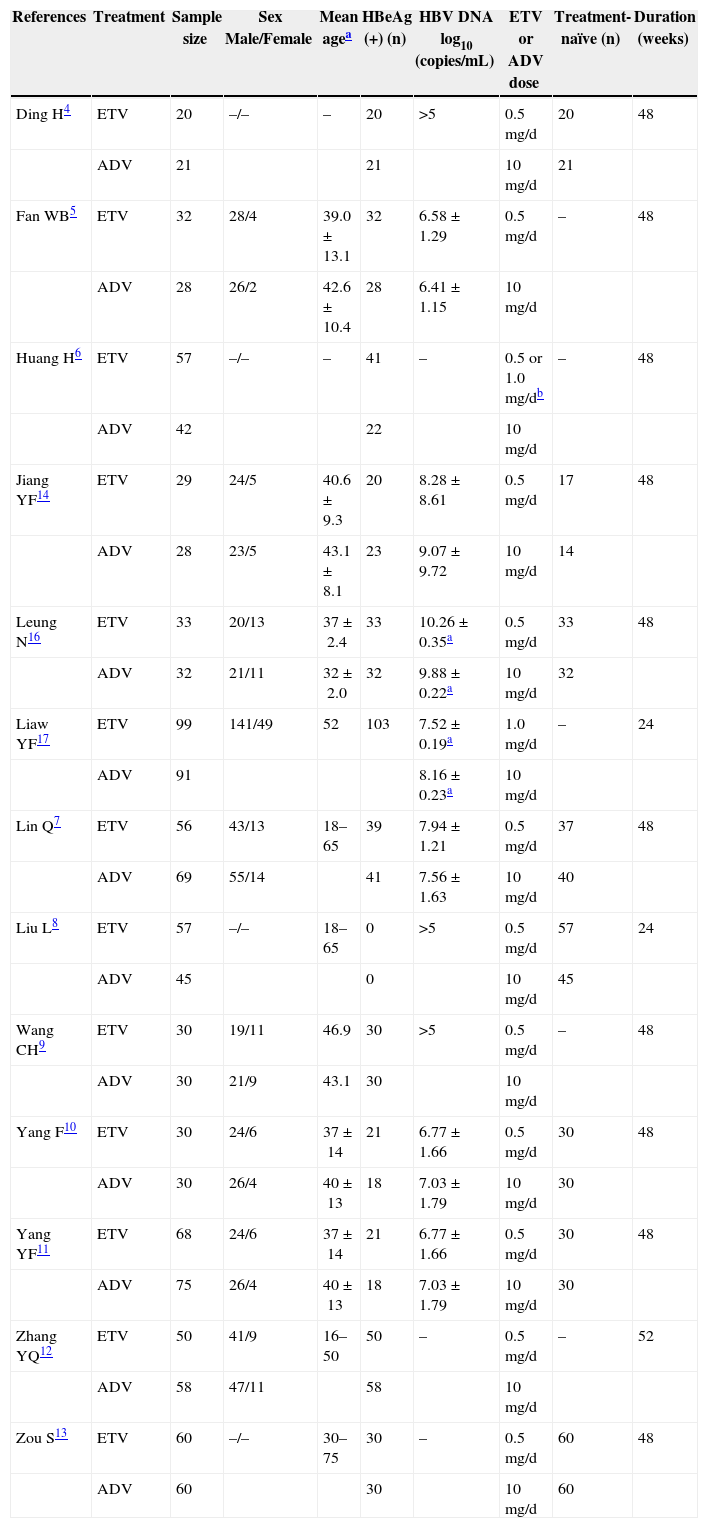

Clinical trial characteristicsThe patients included in the 13 trials were randomly assigned to the ETV or ADV therapy groups. Of the 1,230 patients, 621 were treated with ETV, and 609 were treated with ADV. All included trials were single-center studies. ETV was used at a fixed dose of 0.5mg/day except in the studies by Huang et al., in which the dose was 1mg/day for treatment-naïve patients. ADV was used at a fixed dose of 10mg/day. The baseline characteristics of the patients of the four included trials are summarized in Table 1.

Pre-treatment patient characteristics for the trials included in the meta-analysis.

| References | Treatment | Sample size | Sex Male/Female | Mean agea | HBeAg (+) (n) | HBV DNA log10 (copies/mL) | ETV or ADV dose | Treatment-naïve (n) | Duration (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ding H4 | ETV | 20 | –/– | – | 20 | >5 | 0.5mg/d | 20 | 48 |

| ADV | 21 | 21 | 10mg/d | 21 | |||||

| Fan WB5 | ETV | 32 | 28/4 | 39.0±13.1 | 32 | 6.58±1.29 | 0.5mg/d | – | 48 |

| ADV | 28 | 26/2 | 42.6±10.4 | 28 | 6.41±1.15 | 10mg/d | |||

| Huang H6 | ETV | 57 | –/– | – | 41 | – | 0.5 or 1.0mg/db | – | 48 |

| ADV | 42 | 22 | 10mg/d | ||||||

| Jiang YF14 | ETV | 29 | 24/5 | 40.6±9.3 | 20 | 8.28±8.61 | 0.5mg/d | 17 | 48 |

| ADV | 28 | 23/5 | 43.1±8.1 | 23 | 9.07±9.72 | 10mg/d | 14 | ||

| Leung N16 | ETV | 33 | 20/13 | 37±2.4 | 33 | 10.26±0.35a | 0.5mg/d | 33 | 48 |

| ADV | 32 | 21/11 | 32±2.0 | 32 | 9.88±0.22a | 10mg/d | 32 | ||

| Liaw YF17 | ETV | 99 | 141/49 | 52 | 103 | 7.52±0.19a | 1.0mg/d | – | 24 |

| ADV | 91 | 8.16±0.23a | 10mg/d | ||||||

| Lin Q7 | ETV | 56 | 43/13 | 18–65 | 39 | 7.94±1.21 | 0.5mg/d | 37 | 48 |

| ADV | 69 | 55/14 | 41 | 7.56±1.63 | 10mg/d | 40 | |||

| Liu L8 | ETV | 57 | –/– | 18–65 | 0 | >5 | 0.5mg/d | 57 | 24 |

| ADV | 45 | 0 | 10mg/d | 45 | |||||

| Wang CH9 | ETV | 30 | 19/11 | 46.9 | 30 | >5 | 0.5mg/d | – | 48 |

| ADV | 30 | 21/9 | 43.1 | 30 | 10mg/d | ||||

| Yang F10 | ETV | 30 | 24/6 | 37±14 | 21 | 6.77±1.66 | 0.5mg/d | 30 | 48 |

| ADV | 30 | 26/4 | 40±13 | 18 | 7.03±1.79 | 10mg/d | 30 | ||

| Yang YF11 | ETV | 68 | 24/6 | 37±14 | 21 | 6.77±1.66 | 0.5mg/d | 30 | 48 |

| ADV | 75 | 26/4 | 40±13 | 18 | 7.03±1.79 | 10mg/d | 30 | ||

| Zhang YQ12 | ETV | 50 | 41/9 | 16–50 | 50 | – | 0.5mg/d | – | 52 |

| ADV | 58 | 47/11 | 58 | 10mg/d | |||||

| Zou S13 | ETV | 60 | –/– | 30–75 | 30 | – | 0.5mg/d | 60 | 48 |

| ADV | 60 | 30 | 10mg/d | 60 |

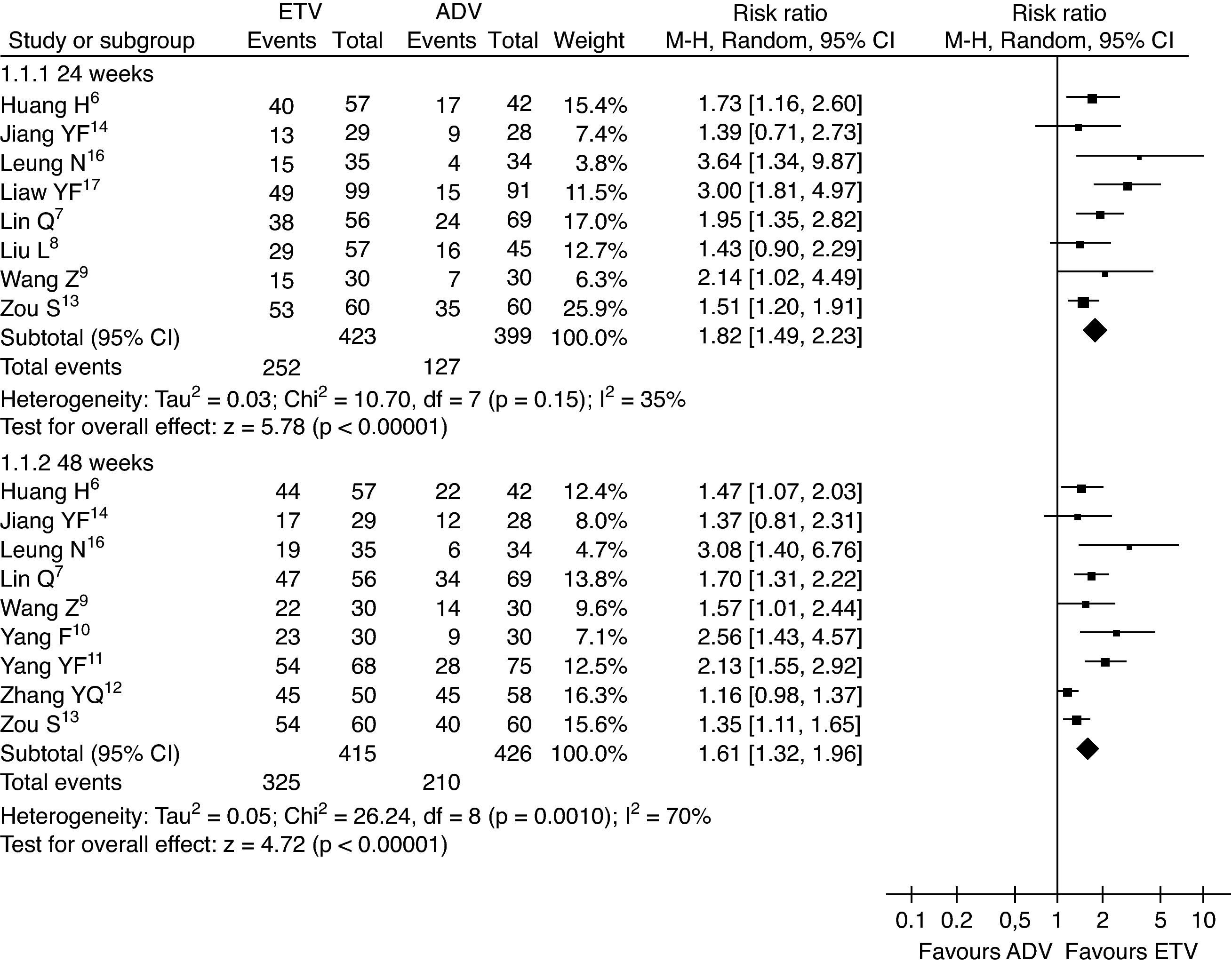

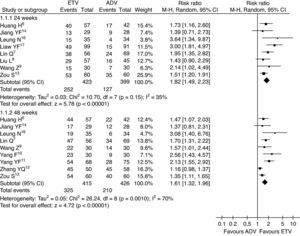

In this study, the combined serum HBV-DNA clearance rate in the ETV treatment group was higher than that in the ADV group at the 24th and 48th weeks of treatment (59.6% vs. 31.8%, RR=1.82, 95% CI: 1.49–2.23, p<0.01; 78.3% vs. 50.4%, RR=1.61, 95% CI: 1.32–1.96, p<0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2).

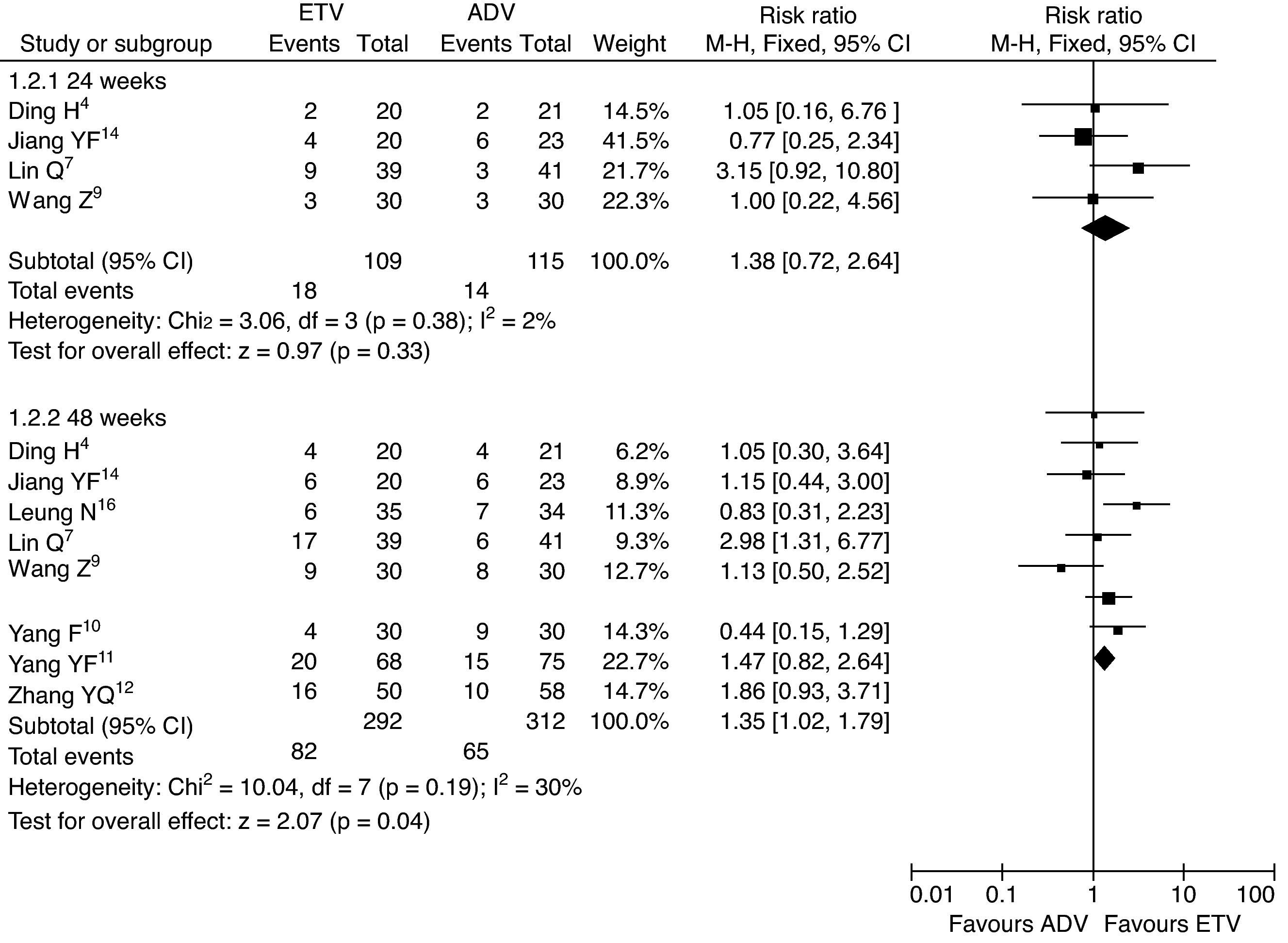

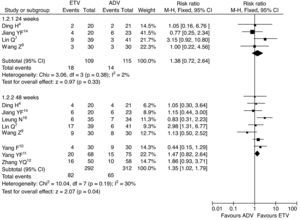

Serum HBeAg clearance ratesThe serum HBeAg clearance rate was also analyzed in this study. Higher serum HBeAg clearance rates were observed in patients treated with ETV than in patients treated with ADV at the 24th and 48th weeks of treatment (16.5% vs. 12.2%, RR=1.38, 95% CI: 0.72–2.64, p=0.33; 28.1% vs. 20.8%, RR=1.35, 95% CI: 1.02–1.79, p<0.05, respectively) (Fig. 3).

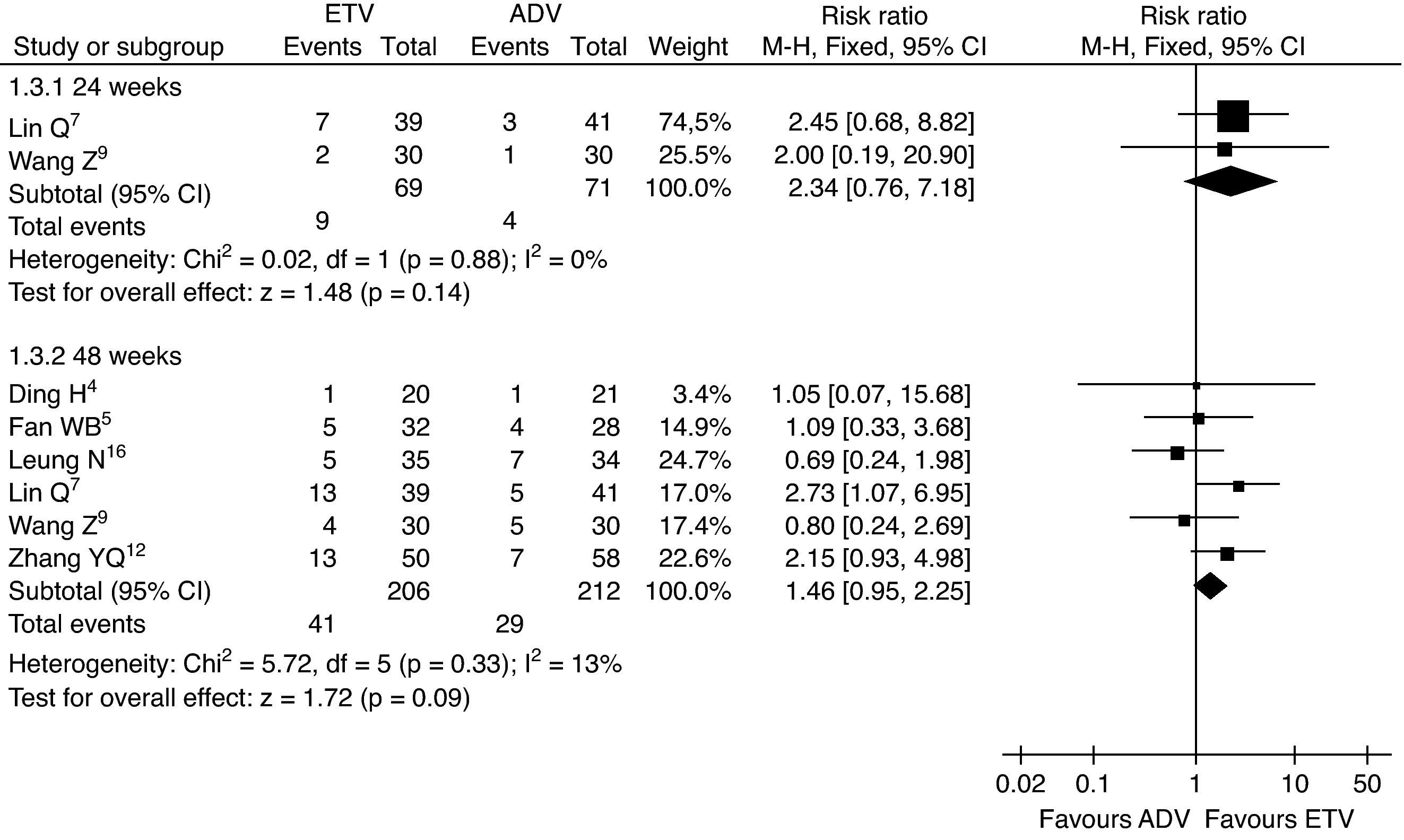

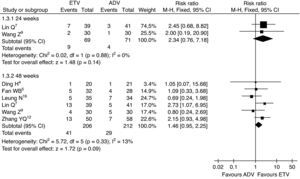

HBeAg seroconversion ratesThe HBeAg seroconversion rates were reported in six trials. The meta-analysis results showed that the HBeAg seroconversion rates were greater for patients treated with ETV than for patients treated with ADV at the 24th and 48th weeks of treatment, but there was no statistically significant difference (13.0% vs. 5.6%, RR=2.34, 95% CI: 0.76–7.18, p=0.14; 19.9% vs. 13.7%, RR=1.46, 95% CI: 0.95–2.25, p=0.09, respectively) (Fig. 4).

HBeAg seroconversion rates, subgroup analysis of ETV vs. ADV in the treatment of hepatitis B patients.

RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; Test for heterogeneity: chi-squared statistic with its degrees of freedom (df) and p-value; I2, inconsistency among results; z, statistic with p-value.

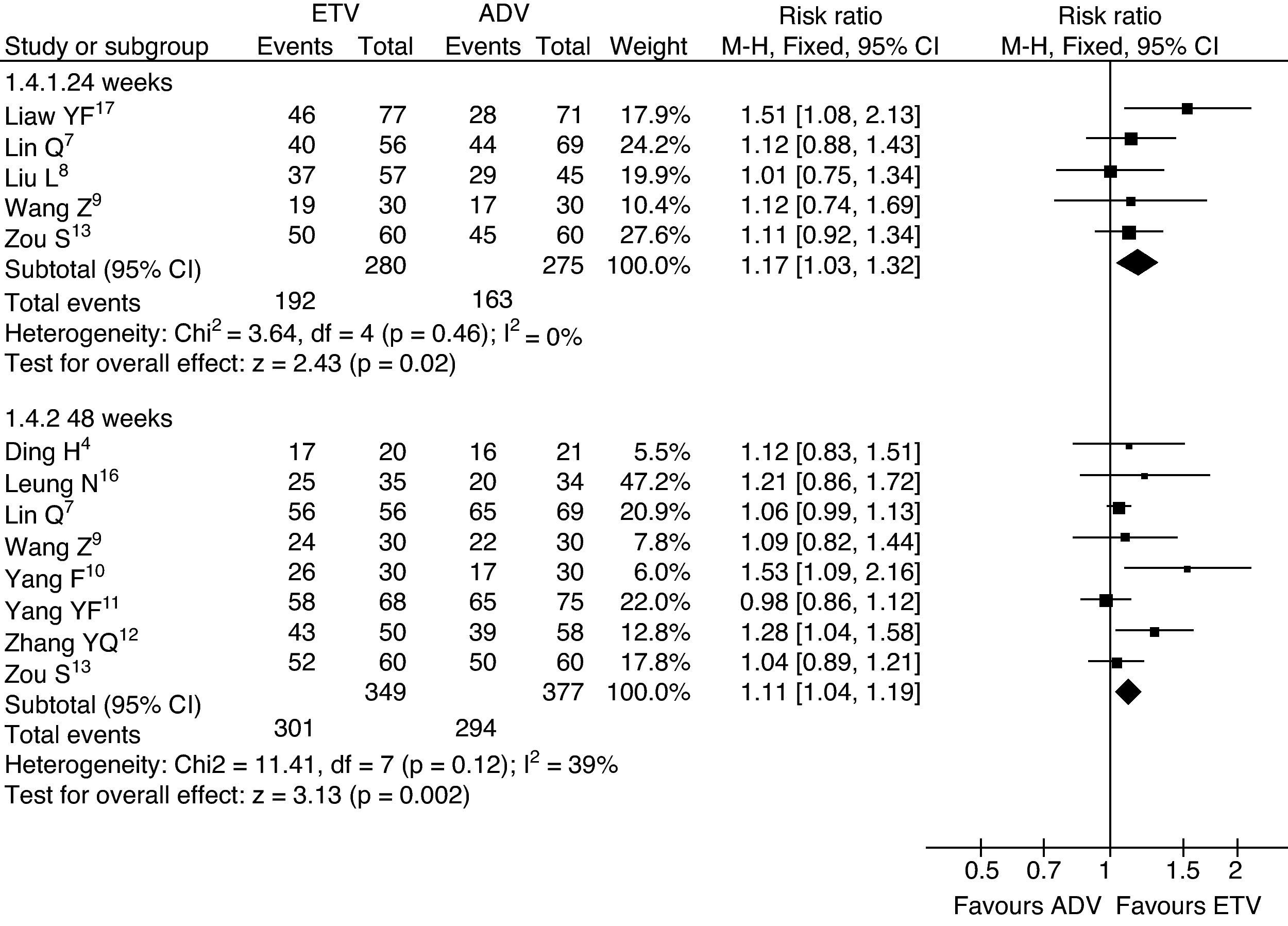

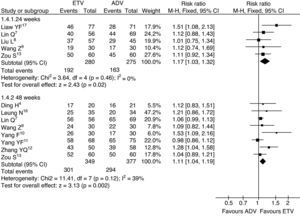

Analysis of the combined data from the included studies regarding ALT normalization was also performed to compare the effect of ETV therapy with the effect of ADV therapy. The combined ALT normalization rates were significantly higher in the ETV treatment groups (68.6% vs. 59.3%, RR=1.17, 95% CI: 1.03–1.22, p=0.02; 86.2% vs. 78.0%, RR=1.11, 95% CI: 1.04–1.19, p<0.01, respectively) (Fig. 5).

Serum ALT normalization rates, subgroup analysis of ETV vs. ADV in the treatment of hepatitis B patients.

RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; Test for heterogeneity: chi-squared statistic with its degrees of freedom (df) and p-value; I2, inconsistency among results; z, statistic with p-value.

Treatment was generally safe and well tolerated. The most frequently reported adverse events included headache, upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, pyrexia, and flu-like symptoms. The differences with respect to overall adverse events or intercurrent illnesses reported in the included trials between patients treated with ETV and those treated with ADV were not significant.

DiscussionHepatitis B is a serious epidemic disease. Liver failure due to chronic hepatitis B is an unsolved medical problem that results in a significant number of deaths. Therefore, treatment strategies for hepatitis B are urgently needed. Lamivudine (LAM), ADV, and ETV are nucleos(t)ide analogs that have been approved for the treatment of chronic HBV infection. These drugs have inhibitory effects on HBV polymerase/reverse transcriptase activity. LAM was the first drug to be approved for the treatment of chronic HBV infection and has been used extensively for more than a decade with an excellent safety record.20 However, prolonged treatment with LAM is limited by the high rates of resistance and by the loss of therapeutic efficacy. More potent agents with lower rates of resistance were sought to provide sustained long-term suppression of viral replication and to prevent the progression of liver disease.

Clinical studies have shown that ADV monotherapy, ADV add-on LAM combination therapy, and ETV monotherapy are all effective in both compensated and decompensated patients infected with LAM-resistant viruses.21,22 Recently, a number of clinical trials have compared the antiviral efficacies of ETV and ADV in patients with CHB infection, but these trials reached inconsistent conclusions. Therefore, a meta-analysis that included a large number of patients was performed to compare ETV with ADV for the treatment of hepatitis B. In comparison with ADV, ETV resulted in higher HBeAg seroconversion rates, serum HBeAg clearance rates, serum HBV DNA clearance rates, and ALT normalization rates in hepatitis B patients in this study. The serum HBV DNA clearance rate obtained in patients treated with ETV was significantly higher than that in patients treated with ADV at the 24th and 48th weeks of treatment (24 weeks: 59.6% vs. 31.8%; 48 weeks: 78.3% vs. 50.4%). The serum HBeAg clearance rate, HBeAg seroconversion rate, and ALT normalization rate obtained for patients treated with ETV were also higher than those for patients treated with ADV at the 48th week of treatment.

Successful antiretroviral therapy may slow disease progression and reduce the incidence of liver-associated mortality. In this study, patients with hepatitis B had a greater likelihood of achieving a viral response and a biochemical response with ETV than with ADV. These results demonstrated that the antiviral efficacy of ETV was superior to that of ADV in patients with chronic HBV infection. Both ETV and ADV were shown to be well tolerated, and these drugs had similar safety profiles. Discontinuations for safety reasons were similar for patients receiving ETV and those patients receiving ADV. Therefore, it is currently believed that ETV is the better treatment for hepatitis B. It is important to mention the limitations of this meta-analysis. A blind method was not used in all included trials, which may be a limitation. Although the heterogeneity was not significant among included trials, publication bias could not be completely avoided.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.